Agadez: voices from a historical transit hub

Introduction

An arid, landlocked state in West Africa, Niger is 1,267,000 km in size and shares borders with Libya, Algeria, Nigeria, Benin, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Chad. Due to its location, Niger has long been a crossroads for trans-Saharan migration via caravan routes that linked the Mediterranean to Africa. The Agadez region, ‘where the Sahara embraces the Sahel’, accounts for 52% of the total area of Niger and is the largest territorial subdivision in Africa. The city of Agadez has for centuries been an important hub for both commercial trade and human migration between West and North Africa. In recent years, it has acted as a strategic location within the trans-Saharan irregular migration corridor, where diverse migratory routes from across West Africa converge in mixed migration flows towards Libya and Europe.

Despite popular belief in Europe, migrants departing sub-Saharan Africa do not all intend to cross the Mediterranean; the intended destinations for many are countries in West or North Africa. Historically, northbound routes across West Africa have been used for both human cargo and commerce; often, vehicles travelling to Libya to collect goods would transport migrants northwards, for a fee, to cover costs of the journey. Since the 1990s, however, these patterns have been interrupted by instability and conflict in the region. ECOWAS states have historically been transit, receiving and sending countries for migrants, resulting in regular and common migration flows between these states. Research shows that even amongst those who move northbound to countries such as Libya or Algeria, comparatively few aspire to cross the Mediterranean to Europe: 84% of migration flows occur internally within the ECOWAS region.

In recent years, three-quarters of all African migrants arriving by boat in Italy have transited Niger, with flows having increased significantly from the year 2000. Conservative estimates suggest that since then, 100,000 migrants have passed through the country each year. A large increase in mixed migration flows occurred after the fall of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, when the smuggling industry in Libya professionalised and became more dynamic and ruthless, increasingly taking advantage of vulnerable irregular migrants. A breakdown of the state’s governance structures in Libya, combined with increased militarisation in the country marked a crossroads for the human smuggling market. Thus, environmental, socio-economic and political realities as well as high levels of political instability in Libya and other countries in the region have fuelled an increase in migratory flows northwards. Thereafter, hundreds of thousands of migrants passed through Agadez; by 2017, there were approximately 330,000 migrants on the move through the country.

Sunset. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

The Agadez region was previously a popular destination for Western tourists providing income-generating opportunities to the region that were crucial during seasons of poor agricultural yields. Laying claim to the world’s highest mudbrick minaret, the neighbouring Aïr Mountains, and, until 2007, hosting the Paris-Dakar Rally, many locals in Agadez profited from the tourism industry, which brought demand for services such as accommodation, food, transport, and tour guides. However, the tourism industry was all but obliterated as a result of the Tuareg Rebellions of the late 2000s and widely publicised kidnappings of foreign workers in the country.

Enterprising locals in Agadez with previous experience in tourism and navigating the harsh desert surroundings took up roles as passeurs (smugglers) whose livelihoods depended on ferrying mostly West African migrants to Libya. This type of transit migration was perceived by the Agadez local government as an alternative livelihood to the diminished tourism industry. Ex-combatants of the former armed resistance were provided, as part of a socio-economic integration programme, with papiers de courtage; papers giving them legal permission to transport people to Algeria from Agadez. Helped by pre-existing infrastructure for tourism and the availability of surplus vehicles, the industry prospered. Secondary sectors, including food, lodging, money transfer facilities, and health clinics, among others, emerged to support the burgeoning industry. The government held a significant financial stake in the form of a visitor's tax, and bribery and extortion lined the pockets of the poorly paid security forces. Thus, a migration-driven economy quickly emerged to fill the vacuum left by tourism, albeit in a limited and transitory way: most migrants only stayed for short periods in Agadez, restricting the industry’s sustainability and making the economy vulnerable to external politics, which has made finding sustainable economic alternatives difficult.

As the "refugee crisis" began to dominate European politics and media, the Sahel region, and Niger specifically, began to attract the attention of European policy-makers. The familiar juxtaposed narratives of migrants and refugees being both a threat to Europe’s security but also in need of saving, played a large role in justifying increased strategic military operations across Sahel states and, in the absence of a legal framework to facilitate lawful migration, laws were introduced to tackle irregular Europe-bound migration. In 2015, prompted by the widely publicised discovery of 92 bodies (largely women and children) found dead in the Algerian desert after being abandoned by smugglers, the Nigerien Government implemented a law criminalizing trafficking and smuggling in human beings: the 2015 Law Against the Illicit Smuggling of Migrants (Loi 2015-36, 26/05/2015; hereafter ‘Law 2015-036’). The law effectively made it illegal for non-Nigerien nationals to travel north of Agadez, and cemented Niger’s position as the southern border of Europe.

Within the first six months of 2017, in excess of 7,800 migrants of different nationalities, were refused entry at Niger’s borders; a refusal rate of 20 persons per 1,000 migrants. In addition to this, data collected at Flow Monitoring Points (FMPs) at Niger’s borders suggest that the new law is at least superficially controlling migration flows towards North Africa and Europe; the number of migrants passing through Agadez to Libya and Algeria have decreased substantially since 2016. By 2017 it also became impossible to count the number of ghettos in Agadez because they had closed and relocated. Individuals who continue to work in the smuggling industry to transport migrants northwards have been forced underground into a shadow economy, and employ increasingly diverse coping tactics: ghetto and departure locations and routes have begun to relocate - to avoid being detected. In addition to this, lookouts are tactically posted in the desert to warn drivers about military patrols, West African migrants are being smuggled among Nigerien workers, and bribes are being paid to police at checkpoints to smooth the way. Such tactics minimise detection by the authorities but pose grave risks to the lives of the migrants.

As this study demonstrates in the analysis chapter, though the numbers of migrants making the journeys northwards has decreased, migration has not stopped.

The implementation of Law 2015-036 has inevitably had far-reaching consequences for the local economy which was intimately tied to the open, state-sponsored industry of migrant transportation. A number of those who surrendered their work in the industry in the wake of the implementation of the law, are now registered recipients of EU-funded business support for alternative livelihoods. Former smugglers must register with the Nigerien government and submit a new business proposal with start-up costs. However, many who registered as part of the program, have yet to receive any assistance. Naturally, the slow progress and limited available industries are becoming a point of contention in Agadez amongst jobless youth, especially those who are used to the lucrative smuggling industry.

Street vendor. Agadez market - © Xchange.org 2018

Niger, and in particular, Agadez, has now become a place of 'containment'. Since the application of Law 2015-036, Agadez has become a temporary, and in some cases unintended, long-term place of residence for different communities of migrants and refugees. These include migrants from Western and Central Africa who are no longer able to continue north to the Maghreb; circular migration populations travelling to Niger for economic reasons; migrants and refugees who have been forcibly deported back to Niger by the Algerian military; and various asylum seekers and refugees who are currently being housed in Agadez. In addition to this, there is the presence of East African migrants who are increasingly travelling to Chad and on to Niger to avoid the dangers of transiting Southern Libya, and migrants returning to Niger from Libya due to failed attempts to cross to Europe, or due to the abuses experienced in that country at the hands of smugglers and authorities. The increased presence of static migrants and refugees residing in Agadez has put a strain on the local economy and on already-threadbare social safety nets. As a result, these dynamics have created tension between the local Nigerien residents and the migrant and refugee communities contained in Agadez, and as this report explains further below, also with humanitarian and international agencies working on the ground with migrant and refugee communities.

Agadez now finds itself stuck at a crossroads; caught between the hypocrisy of Law 2015-036 and ECOWAS’ commitment to free movement, with wide-reaching consequences for the local Agadez community and the migrants and refugees that have found themselves there. In addition to this, government authorities face conflicting financial interests; European funds pouring into the country to counter migration act as incentives, but so do illicit funds more easily earned from migration. These dynamics warrant detailed research and investigation into the changing dynamics of migration, Nigerien and international migrants, international humanitarian and non-governmental actors, and local NGOs.

In 2017, Xchange conducted a survey to obtain reliable first-hand data on routes and incidents from migrants rescued during four different missions aboard the MOAS SAR vessel, The Phoenix, which had been patrolling the Central Mediterranean. The survey served as the basis for the recent Central Mediterranean Survey: Mapping Migration Routes & Incidents report released in June 2018, which provided a meaningful snapshot of the struggles faced by migrants travelling from their countries of origin to Libya, and, for some, on to Europe. The results were both revealing and shocking; the qualitative data demonstrated the complexity of the journeys taken to reach Europe and the extent of the human rights abuses that migrants are likely to experience over the course of their journeys at the hands of smugglers as well as national authorities.

What became clear from interviews conducted by Xchange was that the most treacherous stage of a migrant’s journey precedes the sea crossing.

In our Central Mediterranean Survey, almost all interviewees from West Africa had crossed through Niger to reach Libya. The most significant transit hub before entering Libya was Agadez, which served as a major hub for both West and Central African migrants on the move towards Libya. From our survey, a substantial 61 of 117 (52%) migrants, from five different countries of departure, transited the Nigerien city during their journeys. Agadez was also found to be the second most dangerous location: one in four of the incidents of death witnessed by the interviewees occurred in Niger, most frequently between Agadez and the Libyan border.

Tayo, Nigeria, incident location Madama, Niger.

(Central Mediterranean Survey: Mapping Migration Routes & Incidents)

The findings of the Central Mediterranean Survey provided the basis for part one of this two-part report. The objectives of this study are:

- Gain insight into how international and local stakeholders and local human smugglers experience contemporary shifts to migration flows, particularly since the passage of Law 2015-036.

- Identify whether these recent policy/legal changes and the subsequent submersion of the smuggling industry in Agadez has resulted in more protection risks for migrants making these journeys.

Legal and Policy Framework

In order to understand the complexities and contradictions of the current migration situation in Agadez, it is important to consider the international, regional, and national legal and policy context relating to migrants and refugees in the country.

ECOWAS Free Movement

What is ECOWAS?

ECOWAS aims to promote economic integration of the member countries through adherence to its fundamental principles. Some of which include:

-Equality and inter-dependence of Member States;

-Solidarity and collective self-reliance;

-Inter-state co-operation, harmonisation of policies and integration of programmes;

-Maintenance of regional peace, stability and security through the promotion and strengthening of good neighbourliness;

-Recognition promotion and protection of human and people’s rights in accordance with the provisions of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights;

-Accountability, economic and social justice and popular participation in development.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) was founded in 1975 and is currently comprised of fifteen member-countries, including Niger. ECOWAS was established with a vision of free trade and economic integration as well as free movement, which is considered a priority for the realisation of regional alliance. Aside from United Nations conventions, ECOWAS is the primary institutional framework governing international migration in the West African region. Vision 2020 - introduced in 2007 - confirms ECOWAS’ desire for a ‘borderless, peaceful, prosperous and cohesive region, built on good governance’.

ECOWAS Member countries reaffirmed the principle put forward during the Rabat and Tripoli Conferences, according to which international migration impacts positively on both the host and home country when they are well-managed. They reiterated that within every region of the world, at one time or another in their history, resorting to migration was an integral part of their development process.

ECOWAS’ Common Approach to Migration has the following principles:

- Free movement of persons within the ECOWAS zone is one of the fundamental priorities

- Legal migration towards other regions of the world contributes to ECOWAS Member States’ development

- Combating human trafficking and humanitarian assistance are moral imperatives

- Harmonising policies

- Protection of the rights of migrants, asylum seekers and refugees

- Recognising the gender dimension of migration policies

However, it is worth noting that the implementation of policies on the ground in the West African states is often more complex. There tends to be a lack of harmonisation between national laws and ECOWAS free movement protocols. For example, while some countries allow entry with ID cards both by land and air routes based on bilateral or multilateral agreements, others require travel identity documents in line with the ECOWAS protocols (Ghana and Nigeria). In addition to this, the ECOWAS Commission and Member States have recognised issues concerning harassment at border crossings by state security officers. This means that, in practice, ECOWAS countries’ citizens can be hindered in their cross-border travel; quite frequently, these individuals travel without identity documents due to a lack of basic knowledge of ECOWAS free movement rules. This invariably results in exploitation by smugglers and traffickers, as well as by security officials at border.

Though ECOWAS was originally created as a partnership between countries with similar economic development and security concerns in a bid to strengthen cooperation and understanding, the focus recently has shifted towards issues of security and irregular migration. In August 2017, in preparation for the Global Compact on Migration, and following a meeting among the Migration Dialogue for West Africa (MIDWA) Border Management Working Group, ECOWAS announced it was stepping up efforts to reduce irregular migration within the region. However, it continued to emphasise on the need to address migration without criminalising it, as well as on efforts to work on realising the goals of the Support to Free Movement of Persons and Migration in West Africa (FMM) programme which encourages the free movement of people across West Africa by supporting the ECOWAS Free Movement Protocol.

The Global Compact for Migration

The Global Compact for Migration is the first-ever UN global agreement on a common approach to international migration in all its dimensions.

It is grounded in values of state sovereignty, responsibility-sharing, non-discrimination, and human rights, and recognizes that a cooperative approach is needed to optimize the overall benefits of migration, while addressing its risks and challenges for individuals and communities in countries of origin, transit and destination.

Sultan's palace of Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

EU framework

Despite currently sitting at the bottom of the Human Development Index, Niger is the biggest per capita recipient of EU aid in the world. This paradox is largely explained by the prominent place the Sahel has in EU policy with irregular migration in the region currently standing at the top. As a result, Niger – commonly referred to as ‘the last country before the Sahara’ – has in recent times become the target of international attention and funding, to curb migrant flows heading northwards to Europe.

UCAP Sahel Niger, also known as the European Union Capacity Building Mission in Niger, was launched in 2012 as a civilian mission under the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). EUCAP Sahel ”aims to help establish an integrated, coherent, sustainable and Human rights-based approach among the various Nigerien security actors in the fight against terrorism and organised crime. As such, the mission is designed to provide advice and training to support the Nigerien authorities in strengthening their capacities.”

In 2015, the mission’s mandate changed to include the fight against irregular migration and related criminal activities.The Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF) for stability and addressing root causes of irregular migration and displaced persons in Africa was established at the Valletta Summit. A priority area of the Fund aims to foster stability and more efficient migration management in the Sahel region, the North and the Horn of Africa, particularly through capacity building in third countries. By creating better economic and education opportunities, strengthening the rule of law and national governance, as well as strengthening regional capacity for return and reintegration of migrants, the EU aimed to reduce the loss of life at sea. Projects within the EUTF umbrella include prevention and contention of irregular migrants, return and reintegration into home countries and legal migration and mobility.

Africa-EU Diaspora Development Platform (ADEPT): In 2015, the European Agenda on Migration was created in response to the increased flow of migrants making their way to European shores through the Eastern, Central and Western Mediterranean routes. The agenda had a number of immediate and medium-term responses, which included a significant increase in the budget of the European Border and Coast Guard Agency’s operations at sea, FRONTEX. Additionally, the European Agenda on Migration led to increased actions targeting criminal smuggling networks, the activation of emergency systems to allow asylum seekers to relocate, and the creation of a pilot multi-purpose centre in Niger, operated together with IOM and UNHCR. The latter was created with the aim of increasing the level of information among migrants about the dangers of the journey, ensuring protection at the local level, and providing assistance in case of voluntary return. Thus, through the medium-term responses, the European Agenda on Migration planned on reducing the incentive for irregular migration, reinforcing border management to save lives and securitising external borders, strengthening the Common Asylum policy, and developing a new policy on regular migration.

Building. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

National framework

Until recently in Niger, migration has been treated with a laissez-faire approach at the national level. That said, there are several national laws in place concerning irregular migration and trafficking in persons; although, implementation of these laws and the resultant removal of migrants have been largely due to reported criminal and terrorism offences. Despite a special inter-ministerial committee on migration policy development in 2007 and the elaboration of a first draft policy document in 2014, a national migration policy still has not been adopted. However, Niger has been party to several Euro-African intergovernmental meetings, in Rabat and Tripoli in 2006 and in Lisbon in 2007: ‘The first Euro-African ministerial conference’ in Rabat in 2006 which set up three working groups on the themes “Migration and Development” (Dakar, July 2008), “Legal Migration” (Rabat, March 2008) and “Irregular Migration” (Ouagadougou, May 2008).’

Bilateral agreements

In addition to this, Niger has, since the 1970s, entered into a number of bilateral agreements with neighbouring countries, on entry and residence of their nationals. In the case of its northern neighbours, Algeria and Libya, the countries have signed the following conventions:

- Convention with Algeria, 1981: visas are required for nationals of Niger to enter Algeria and vice-versa, while article 5 ‘includes a provision on readmission of migrants in an irregular situation’.

- Convention with Libya, 1971, 1988: The 1988 convention ‘guarantees the general civil and economic rights of the considered individuals’ while the 1997 convention offers ‘a specific legal regime for Nigerien seasonal workers in Libya', such regime ‘foresees the delivery of a three-month visa, and a stay permit valid for one year, which is renewable up to a limit of two years’.

However, within the ECOWAS Common Approach to Migration, it is recognised that:

...it is clear that bilateral agreements concluded by some ECOWAS Member States with host countries are not sufficient to address these multi-dimensional problems. ECOWAS Member States undertake to strengthen their cooperation with regard to controlling irregular migration within the ECOWAS framework.

Moreover, Niger – together with Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali and Mauritania – is part of the “G5 Sahel” group, set up in 2014 to foster close cooperation and tackle major challenges in the region. The G5 initiative deals with a wide range of issues: political dialogue, development and humanitarian support, strengthening security and tackling irregular migration. Many of the EU policy mechanisms, as a result, address the group, rather than Niger individually.

The 2015 Law Against Illicit Smuggling of Migrants

Law 2015-036, the ‘law pursuant to the illicit trafficking of migrants’ was approved unanimously in 2015 by the Nigerien parliament and represents a turning point for transnational movement in the region. The law was presented as promoting the human rights of migrants and criminalising their transportation as well as how to proceed to return of ‘victims of illicit trafficking’. The law falls in line with the EU-supported push for the limitation and control of migration through policies implemented in the region, viewing human smuggling networks facilitating migration as criminal syndicates and terrorist threat as a priority. Thus, in an attempt to reduce instability in the region, the Nigerien government welcomed the law to reduce the likelihood of money making its way to fund terrorist activities.

Migrants from the ECOWAS country-members passing through Agadez theoretically have the right to travel up to Agadez – however, the law has had the effect of portraying all migrants as illicit and presenting a singular solution to as returning them to their country of origin. In doing so, and as demonstrated in the analysis chapter of this report, the law ‘criminalises the activities of those who facilitate the irregular entry, stay and exit of migrant persons, including those who procure or possess fraudulent travel or identification documents’ and ‘allows for the detention of migrants subjected to illicit smuggling without clarifying the grounds for such detention' - and by doing so, migrants are being pushed into hiding, thereby making them more prone to human rights violations.

Agadez - ©️ Xchange Foundation/Ioannis Papasilekas - 2018

Methodology

Fieldwork-Data Collection

The present research employed a cross-sectional and exploratory qualitative methods design. Fieldwork informing this report took place in Niamey and Agadez, Niger between October 23 and November 13, 2018. The Xchange research team attended a total of 38 meetings consisting of in-depth and key-informant interviews and formal and informal individual and group discussions; 26 took place in Agadez, 8 in Niamey, and 4 remotely.

Arrivals. Agadez Airport - © Xchange.org 2018

Road. Niamey - © Xchange.org 2018

Data collection in the form of in-depth interviews was done over the course of one month, between October 25 and November 27, 2018. Research participants were identified and purposively chosen primarily via chain sampling and participation was done on a voluntary basis. A pilot interview took place remotely a couple of weeks before fieldwork began to evaluate the interview questions and methodological approaches and organising further meetings with a number of participants.

In total, 22 in-depth interviews were conducted with the use of semi-structured interview guides; 19 with individuals and three with two or three colleagues who worked for the same organisation. 21 of the in-depth interviews were recorded with a conventional recorder, transcribed, and analysed for the purpose of this report;

- Seven of these were with international NGOs,

- Two were with local government officials,

- Four were with individual actors,

- Three were with local NGOs, and

- Five were with (ex-) passeurs or coxeurs.

Most interviews were conducted in French, by either one or two researchers and often with the help of one or two interpreters depending on the needs of each interview. In detail, ten interviews were conducted in French, eight in English, two in both French and English, one in Hausa and French and one in Italian. The length of the interviews ranged from 25 to 75 minutes with a median time of 41 minutes.

Interview with an Ex-Passeur. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Interview Analysis

All recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim either in English or French. The latter were subsequently translated into English for the purposes of the analysis. The process of transcription and translation lasted roughly one month following the data collection period. The transcripts were subsequently coded and analysed qualitatively. In total, the identified codes were grouped into roughly 40 ‘code families’ which formed the sections of each sub-chapter of the Findings.

Ethical Considerations

The purpose and objectives of the project were explained to all interview participants prior to the commencement of each interview. Each participant read and signed an informed consent form detailing their voluntary participation and their right to withdraw from the study at any time. None of the participants were financially rewarded for their participation.

Only the Xchange team had access to the original recordings and the transcripts of the interviews ensuring the participants’ confidentiality. Moreover, during the report-writing process, pseudonyms were used to protect the participants’ identities and preserve their anonymity. Certain participants, such as the President of the Regional Council of Agadez and the Sultan of Agadez, did not wish to remain anonymous.

Limitations

Overall, all interviews were successfully completed without any disruptions. However, there were several limitations observed associated with data collection.

Many potential research participants did not agree to be interviewed on a voluntary basis, demanding instead to be paid for their time. This phenomenon which was particularly prevalent among (ex-) passeurs and coxeurs - consequently limited opportunities for data collection. However, that no participants were paid increases our confidence that information was provided to the research team in good faith.

The presence of foreign researchers may have limited participants’ willingness to divulge information. However, the local interpreter assisted significantly in minimising bias and filling in cultural gaps where needed.

On the other hand, the fact that two interpreters were used in many cases interrupted the train of thought of some participants. As the researchers were not fluent in French, one of the official languages of Niger, language competency presented limitations during a number of interviews. Language issues might have, in turn, prevented the interviewers from asking potential follow-up questions. As a result, information might have been withheld from the interviewers at the time of these interviews. Likewise, time limitations did not allow the researchers go into desired depth in a number of interviews.

Findings

Chapter 1: The criminalisation of an industry

Changes since the implementation of Law 2015-036

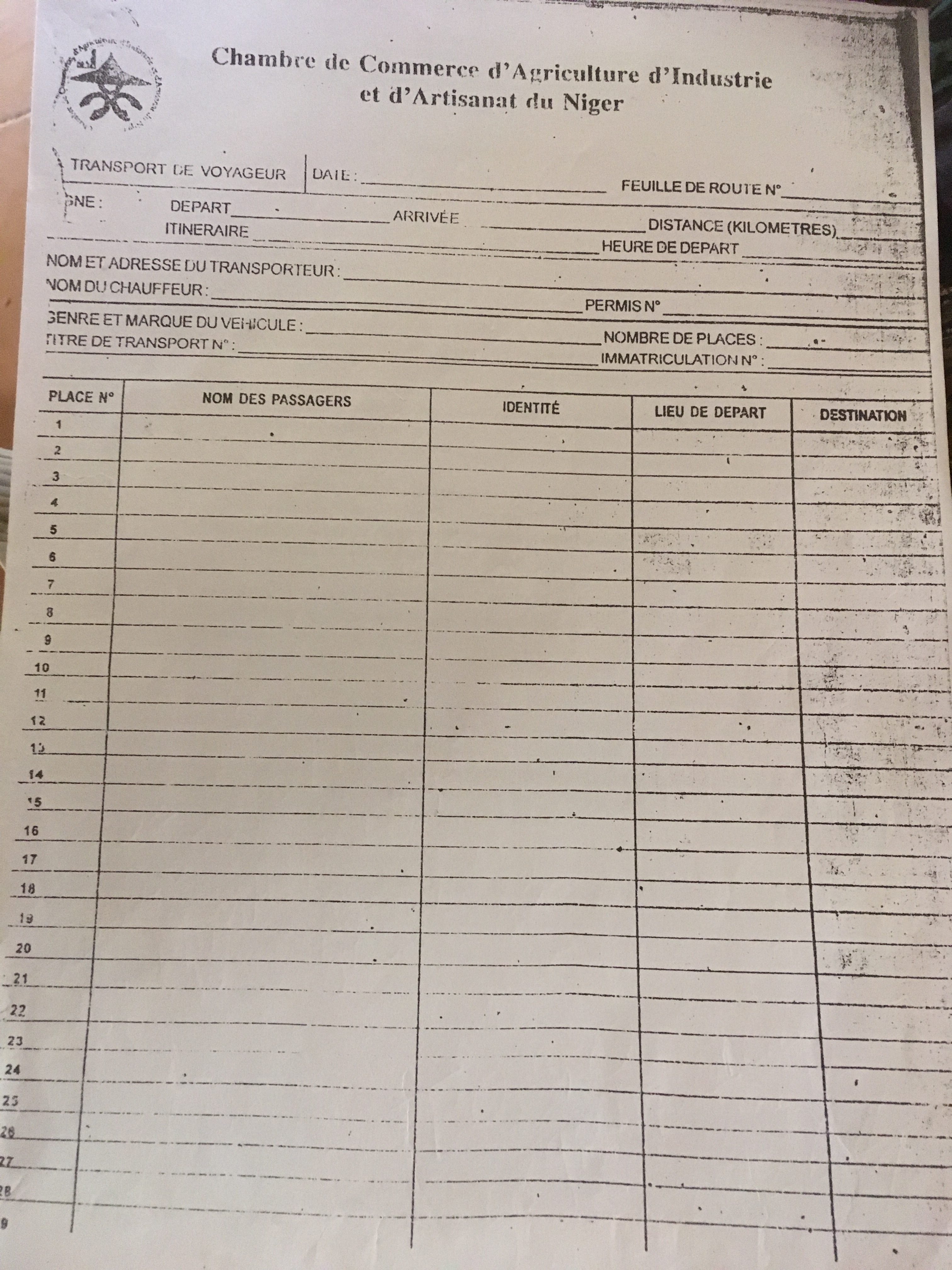

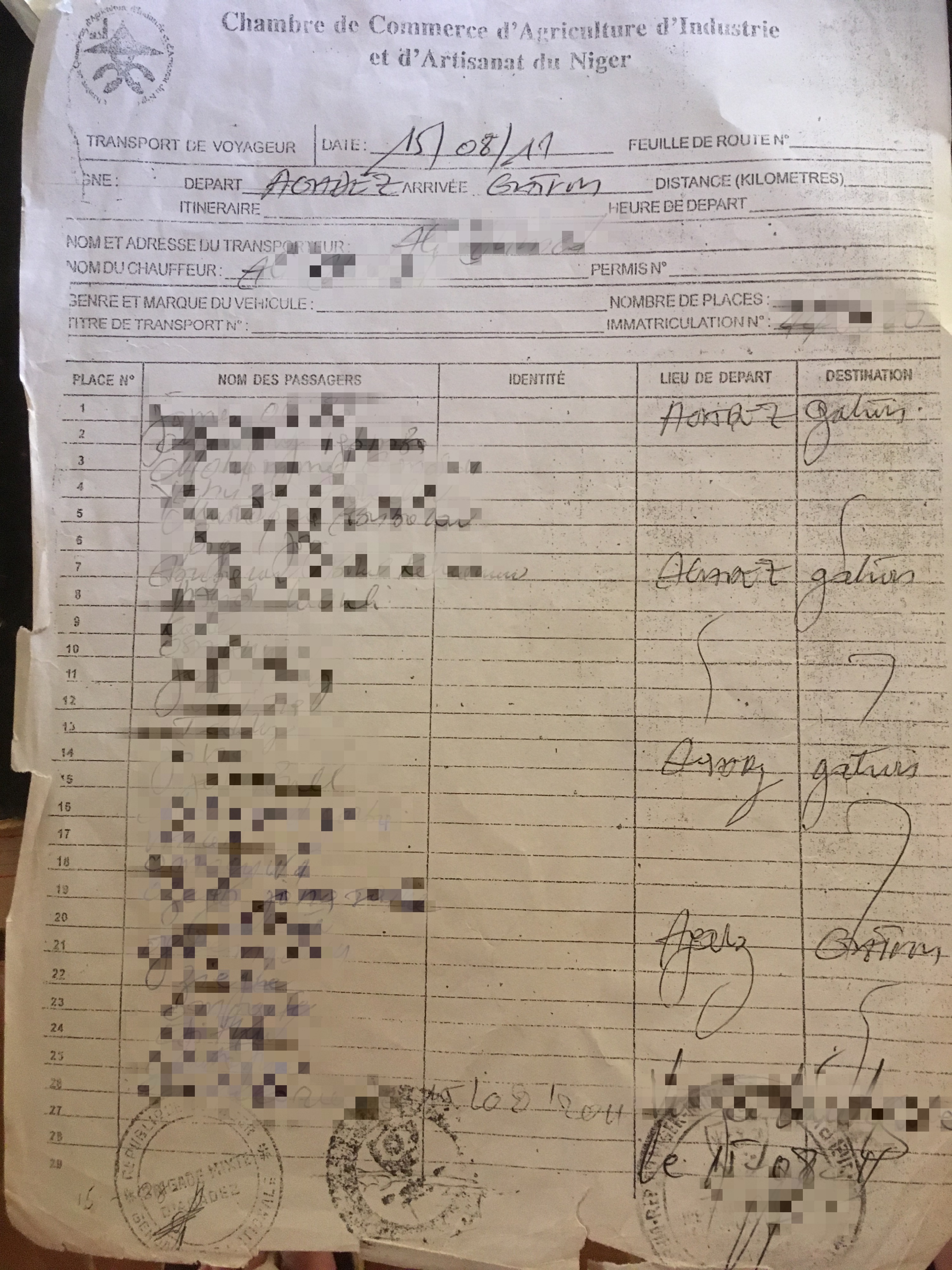

Migration is intrinsic to West Africa, and Niger has been a sending, receiving and - most importantly - transit country for centuries. One of the first findings of this study is the difference in regulation of the migration industry before and after Law 2015-036 was implemented by the Nigerien government. Before it came into effect, the industry was regulated: those transporting migrants were recognized official workers, who would pay taxes and whose activities were overseen by the state. It was standard practice for transporters to inform authorities of the number of migrants they were transporting and the route they were taking.

M. Anacko, President of the Regional Council of Agadez

With the adoption of the Law 2015-036, the transport of migrants north of Agadez was no longer permitted and, as a result, regulation of the industry became incompatible with national legislation. Most of our interviewees agreed that instead of making the industry disappear, the change in national legislation drove it underground. As M.Anacko put it, ‘no one can stop them. And they will always continue because they have nothing to do.’.

One of the major implications of a lack of regulation of transport of migrants has been the increasingly precarious conditions under which the industry now operates. The traceability and accountability that once existed with official oversight has all but disappeared. The chain of responsibility between those transporting migrants, intermediaries, and police forces, is no longer in force and as such does not act as a protection mechanism to mitigate potential risks to migrants attempting the treacherous journey. As one passeur narrated:

Passeur

Another reason for the lack of traceability since the implementation of Law 2015-036 is that whereas passeurs and coxeurs have historically been local people from Agadez, familiar with the geography of the region and known to locals, smuggling is now carried out by foreigners, people ‘from Libya, from Chad, from Algeria that we do not know’ (Activist and President of Nigerien NGO).

The vast majority of the people we talked to indicated that before the implementation of the law, passeurs and coxeurs, the authorities, the police, the military, and the migrants often knew one another and were in regular communication. Thus, beyond official government regulation, there existed social regulation and protective mechanisms within the industry.

M. Anacko, President of the Regional Council of Agadez

According to Nigerien participants, the lack of contextual understanding from external actors is what led to the criminalisation of the industry and the profession. An important finding is that terms such as passeur, coxeur, smuggler, trafficker, driver are not clearly understood, and will often be used interchangeably by Western politicians and journalists alike. Several interviewees offered to explain what each job involves.

Activist and President of Nigerien NGO

"Mairie Agadez": Town hall of Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

An industry driven underground

As the majority of participants reported, migration via Niger - and most importantly, Agadez - has not stopped. Since time immemorial, migration has been an important facet of Agadez, and it is inconceivable that it would ‘end’. Rather, migration in Niger has adapted to meet the prevailing political climate and will continue to do so in novel ways because of efforts to restrict irregular migration.

Many participants used the term “clandestine” to describe the contemporary situation of migration in the region of Agadez. M. Anacko, President of the Regional Council of Agadez, explained why referring to migration as “clandestine” is very relevant today but was not five years ago:

M. Anacko, President of the Regional Council of Agadez

The consequences of the industry becoming clandestine are far reaching and diverse. Most significantly, there are increased protection risks to migrants attempting the journey north. With no regulations in place due to the criminalization of the entire industry, those trying to travel northward, and who often cannot return home, are left with no option but to take new, more dangerous routes, overseen by less scrupulous smugglers.

M. Anacko, President of the Regional Council of Agadez

Corruption and extortion of irregular migrants

As a consequence of the implementation of the law and the increase in funds coming from the EU to tackle border management, some representatives of INGOs in Agadez have reported an increase in police corruption and extortion of migrants. While taking advantage of their positions and displaying a general lack of knowledge of Law 2015-036, police have been accused of setting up road blocks as a way to extort migrants.

Migration Coordinator, International NGO

This view has also been supported by representatives of local NGOs, who argued that the police, aware that migration northwards is still occurring in Niger, will learn about the route being taken by migrants and ask for bribes on the road. However, one former travel organizer was reluctant to comment on the activity of Nigerien police, but did mention that police across the region demanded bribes of migrants. While not all members of the police force engage in extortion of migrants, interviewees narrated some instances where migrants were exploited:

Activist and President of Nigerien NGO

Clothes by Niger River. Niamey - © Xchange.org 2018

The state’s implementation of Law 2015-036

With a military presence established throughout the region, road blocks, ghetto raids and car seizures have become the norm since the implementation of Law 2015-036. As one passeur expressed:

Passeur

Niger’s commitment to putting an end to migrant smuggling has been implemented through increased police retaliation and action. Many interviewees narrated how arrests have become the norm for anyone traveling North of Agadez with migrants:

Passeur

Once police find smugglers attempting to travel North, this often results in the drivers being arrested and sent to prison, and their cars being seized. A number of our interviewees ‘went to jail’ and recounted that prison sentences usually last between six months and one year:

Passeur

One interviewee reported that prison sentences depend on the smuggler’s role within the industry and the number and the nationalities of migrants being transported. Punishment allegedly tends to be greater for the driver of the car, regardless of ownership, and this also seems to be the case when those being transported are foreigners instead of Nigerien citizens.

Passeur

The climate of persecution and prosecution has reportedly led to tensions in the region. Some of our interviewees told of the increase in reporting of individuals involved in the smuggling industry which subsequently drags the industry further underground:

Ex-Coxeur 1

In addition, it was reported that a lot of uncertainty and lack of clarity surrounded the implementation of the law, often leading to the police and state actors being unsure about how they should proceed. This view was also supported by representatives of INGOs in the region, who believed the lack of clear instructions on how to execute the new legislation meant that often state actors ‘didn’t know what to do with smugglers and the ghetto leaders they would find’ (Migration Coordinator, International NGO). This suggests the law was introduced too quickly, without full consultation and training of actors in the local community, as to how in practice the law should be enforced.

As a result of the profound risks and implications for those still working in the industry, some of our interviewees who were coxeurs and passeurs reported no desire to go back to working in the industry. When asked whether he would consider working as a coxeur again, an interviewee replied:

Ex-Coxeur 2

This, however, is not true of everyone. Some individuals continued working in the industry; motivated by the large financial reward which could not be earned in any alternative livelihood in the region, coupled with the lack of alternatives currently available in Agadez.

Activist and President of Nigerien NGO

Passeur

Agadez streets - © Xchange.org 2018

EU border management

It became clear from interviewees that the EU strategies being implemented in Niger are at odds with the desires of the local Nigerien population, who 'want to deregulate the problem of migration [and] the Europeans want to regulate the problem of migration’ (M. Anacko, President of the Regional Council of Agadez). A history of European interference in West Africa was addressed by several interviewees. The president of a local NGO and activist criticised:

Activist and President of Nigerien NGO

The UNHCR Country Representative added that by focusing on the strengthening of borders, EU policies are leading to further human rights violations. By prioritising short-term goals through the adoption of immediate ‘containment’ policies, EU policies overlook the abuse and neglect inflicted upon migrants.

Chapter 2: The changing realities of migration

Changing dynamics

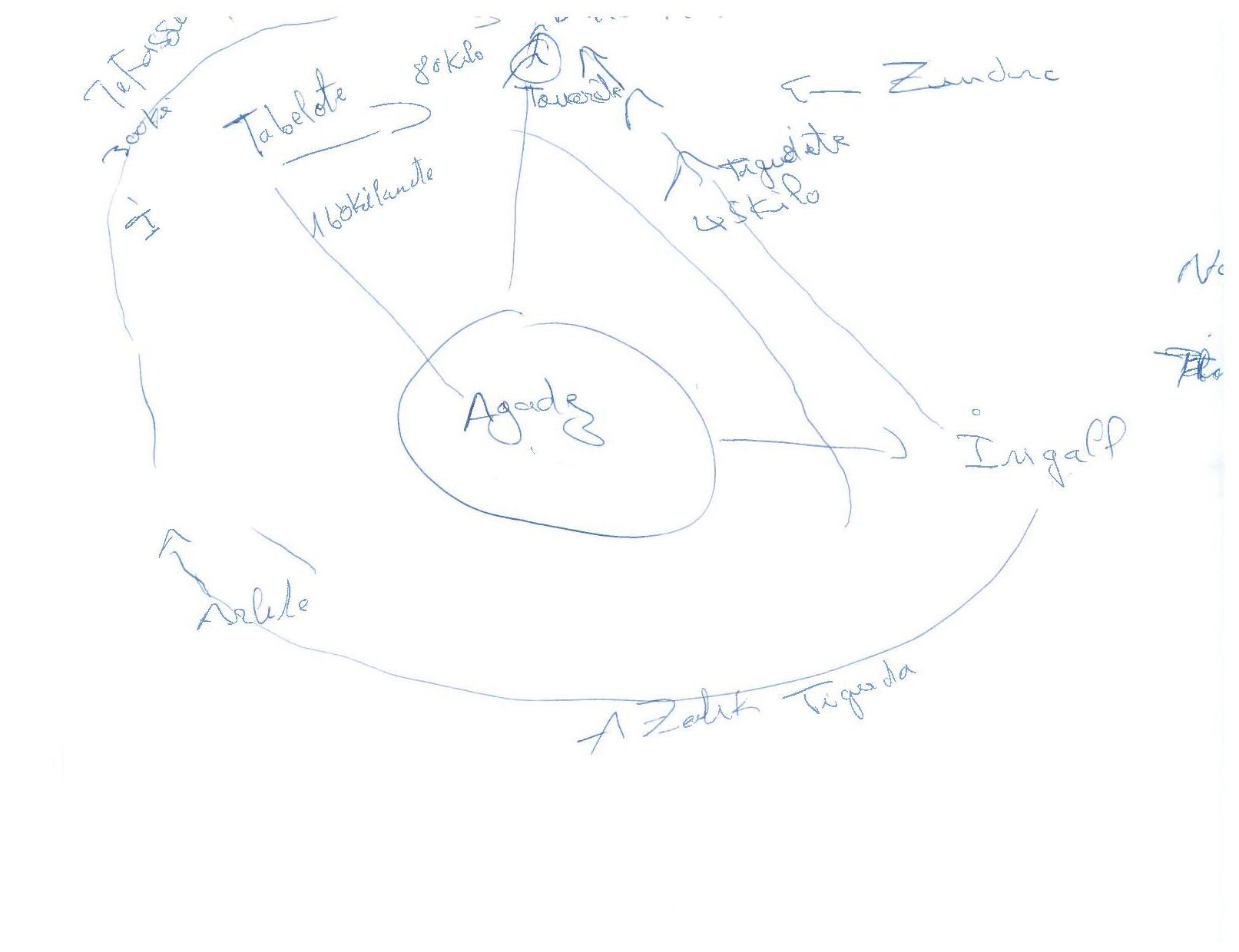

According to a majority of interviewees, geography has played a key role in changing migration dynamics since the law was implemented in 2015. Agadez’s unforgiving desert landscape has allowed the continuation of migrant transport northwards without detection albeit with increased dangers.

Nigerien Activist 1

This view was also supported by the UNHCR Country Representative, who believed that ‘the entire Sahel is now the route’. She highlighted that the implications of this are increased risks for anyone attempting the journey, as non-traditional routes are longer, generally more expensive, and further away sources of potable water.

UNHCR Country Representative

The Sahara Desert acts as a natural border between Niger and North Africa, and even though the journey is a perilous one, the desert provides plenty of opportunities for experienced drivers to find alternative paths. Routes used by transporters before Law 2015-036 was passed, referred by participants as “traditional” routes, have now shifted:

Deputy Representative, International NGO

Mind map: Nigerien Activist 1 explaining the various existing routes - © Xchange.org 2018

There are multiple alternative routes currently employed by smugglers. Some continue to take the route to Dirkou, leaving from Tabelot and Zinder, and there are those who depart from Tahoua to go to Algeria. Participants, however, agreed that all these routes have one thing in common: they bypass Agadez due to a heightened security presence in the city.

In addition to the diversification of routes to Libya and Algeria through Niger, interviewees reported an increase in the number of migrants attempting to cross into Libya via Chad.

Ex-Coxeur 1

With the industry driven underground, the dynamics of migration have also changed. However, as M. Anacko, President of the Regional Council of Agadez, explained, there is no systematic monitoring occurring and hence the exact number of migrants transiting Agadez is unknown. As such, speculations to the extent of migration movements is rife. In his own words:

M. Anacko, President of the Regional Council of Agadez

Consequently, many interviewees reported the inability to make valid claims regarding how migration figures have changed. Activists with connections to ghetto owners where migrants are hiding, criticized those suggesting that the number of migrants has significantly decreased:

Nigerien Activist 2

Moreover, several participants reported that the changing routes have also had implications on the cost of transportation north; the increased danger involved in transporting migrants to Libya or Algeria has led to an increase in price. Both international and Nigerien NGO representatives supported that prices have increased significantly, doubling in many cases.

Migration Coordinator, International NGO

A current passeur who alleged that now he is only working with Nigeriens, explained the difference between transporting Nigeriens and foreigners. He reported that he preferred to transport foreingers over Nigeriens, as the prices charged to the former are always higher and Nigeriens are more likely to be able to find alternative transport.

Passeur

Grand Mosque of Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Agadez: a host community

Agadez has increasingly become a host community for migrants returning from Algeria and Libya. Though Niger remains a transit hub for migrants attempting to travel North, increasing numbers of Nigeriens and foreigners have ended up in Agadez having attempted and failed to make their way to either North Africa or Europe. Many reported that the Nigerien returnees who were expelled from Algeria and ended up in Agadez are from the South of Niger and not from Agadez.

Additionally, it has been reported that many migrants traveling to Algeria end up exploited by trafficking rings that force them to beg in the streets. As M. Anacko explained, it is usually migrant children who end up in vulnerable positions in which they can be taken advantage of by traffickers.

Most of the interviewees supported the view that returnees have put a strain on the local economy and resources. As an Assessment Officer of an International NGO working in the area reported, the Government of Niger doesn’t have the capacity to assist all migrants residing in Agadez. It was reported that many migrants went to Agadez suddenly, leaving the local government unable to process everyone in need.

Assessment Officer, International NGO

Within the region, however, Niger remains a cooperative partner, and as such has offered to host migrants whose asylum claims have not been successful or migrants who haven’t been able to reach their desired destination countries. With the help of international agencies like IOM, Niger has established safe houses and temporary transit centers for migrants. As the Deputy Country Director of an International NGO working in the area stated, as a result, migrants are now 'sorta in a holding pattern, so there’s a fair amount of Somalis and Eritreans and others who are sorta now in limbo here in Niger'.

Medical Centre. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Increased risks and vulnerabilities

Transporting people in the Sahara has always been a challenging endeavor for passeurs and drivers.

Passeur

However, as some participants explained, before criminalisation in 2015, the state of the industry was much more regulated. People were not afraid to work with the authorities when their safety was compromised. With the implementation of Law 2015-036, and the industry being driven underground, trust between the various actors has understandably weakened. The changing of routes has had a significant impact on safety of involved actors, as the non-traditional routes being taken are not well-known to all. Though one ex-coxeur reported that migrant deaths have gone down, overall participants agreed that risks have since increased for migrants and the drivers, passeurs, and coxeurs that keep migrants moving.

M. Anacko, President of the Regional Council of Agadez

Ex-passeur

Supplies such as water, food, and fuel, play an important role in securing each migrant’s safe arrival at their destination. Previously, smugglers made pains to ensure that their modes of transport were outfitted with adequate supplies, but this is no longer the case.

Nigerien Activist 1

Deputy Representative, International NGO

As the identification of smugglers has become difficult since they went into hiding, it is easier for them to not be held accountable for their actions. Hence, in order to avoid being detected, they are not afraid to take more risks which could further compromise migrants’ safety.

Director, Nigerien NGO

Sultan de l’Aïr

And this is where, according to INGOs, it becomes a challenge to differentiate between a smuggler and trafficker.

Migration Coordinator, International NGO

As a result, the increased risks in turn increase the likelihood that people will die in transit, and also make migrants more susceptible to trafficking, according to participants. One interviewee referred to Agadez as 'the immigrant trafficking capital', and passeurs admit that now that migration has been deemed illegal, it is more likely that those transporting people are involved in trafficking.

Passeur

Local NGOs are concerned about the rising numbers of children who are trafficked into Algeria from the southern part of Niger, particularly from the region of Zinder.

Permanent Secretary, Nigerien NGO

According to a nurse, the demand for customers is now higher, and because of a lack of traceability and accountability, smugglers will transport anyone, irrespective of whether they can afford the asking price for the voyage. In such cases, it is very likely that these people will be sold to a Libyan intermediary, who will cover for the remaining costs – with the price being the migrant’s freedom.

Nurse

International organisations focused on the migrants’ safety have called into question the existence of measures to protect migrants from exploitation. A UNCHR Representative asked for measures to be put in place in order for the world to know what really is happening.

UNHCR Country Representative

Migration Coordinator, International NGO

Agadez Crossroads - ©️ Xchange Foundation/Ioannis Papasilekas - 2018

Chapter 3: International Actors’ Activity

Reaction to INGO activity

Of the local Nigeriens interviewed, several reported frustration with reference to the presence of local and international humanitarian organisations including IOM and UNHCR. The general perception was that INGOs’ programs were ineffective at serving the needs of locals and Nigerien migrants. Several interviewees reported a lack of communication with INGOs, who they claimed lacked understanding of local needs or how to prioritise them.

An independent actor (Nigerien Activist 1) highlighted the lack of communication between INGOs and local communities to both understand their needs and effectively address them. He felt it is essential that the target group is consulted, to ensure their most urgent needs are met, which in turn will allow more secondary community needs to be addressed, such as social cohesion and stability.

This same actor (Nigerien Activist 1) expressed a lack of holistic care and grassroots support appropriate to migrants’ needs. There is a need for NGOs to offer services such as medical aid or ways to address food insecurity or flooding, he said, while many of these NGOs offer activities that are intended to raise awareness of the challenges involved in making irregular journeys. The prioritisation of awareness-raising projects over vital medical assistance to deal with health-related challenges such as diseases suggests that the wider political (anti-immigration/migration-prevention) agenda takes greater precedence over consulting with affected communities to find out how their needs can be served as a mitigation measure in its own right.

Nigerien Activist 1

Participants reported that NGO staff are often sent into the field without having any understanding of, or previous contact with, migrants and their needs and struggles. This suggests some INGOs’ efforts are far removed from the real needs of the communities they intend to serve, limiting their effectiveness.

Nigerien Activist 2

A further issue expressed by numerous interviewees was mistrust towards INGOs operating in the region, with IOM centres facing the greatest criticism. Multiple independent actors and Nigerien NGO representatives reported the IOM centre in Agadez as being selective to whom they provide humanitarian assistance. Non-Nigerien migrants have reportedly been prioritised by IOM, whereas Nigeriens have been rejected and refused access:

Nigerien Activist 1

The IOM were also criticised for favouring migrants who have agreed to return to their own country. This ignores the complex needs of all migrants, regardless of whether they are returning, remaining in Agadez, or continuing their journey.

Director, Nigerien NGO

This treatment has left many disillusioned by the IOM’s services, and untrusting of their commitment to protect and support all migrants in a fair and equitable manner, as they profess to do.

Several leaders of other NGOs corroborated the idea that larger organisations, such as those overseen by UN agencies, are not considered entirely trustworthy or humanitarian by migrants, since their funding is often conditional on the premise that it is spent on efforts stemming migration.

Migration Coordinator, International NGO

Some NGO leaders also expressed that migrants have had contact with many international actors such as journalists and other organisations, but do not perceive that their situation has meaningfully improved. They have become ‘tired of talking’ (Migration Coordinator, International NGO) and of ‘all the ‘research’ and ‘assessments’ going on in Agadez’ (Deputy Country Director, International NGO). This has led to disillusionment and lack of trust in these organisations amongst migrants. This has been exacerbated by breaches in trust between migrants and researchers: several respondents reported cases of migrants’ requests for anonymity being ignored, putting not just the individual in danger, but also exposing the ghetto in which they are staying to raids by police. As a result, the work of local NGOs trying to serve and support the needs of migrants face increasing challenges. These organisations find it harder to access migrants who are willing to speak about the challenges they face due to migrants' declining trust in international actors.

One Deputy Country Director of an INGO highlighted that Niger as a country suffers from an exceptional lack of coordination and cooperation between organisations working on similar issues. One possible reason for this is that there may be competition for funds amongst organisations.

One local NGO President described the short-term mentality of some INGOs working in the area. He claimed they lacked commitment to the cause, or a desire for their work to be sustainable to benefit migrants’ or locals’ needs in the long-term.

President, Nigerien NGO

Nigerien Activists expressed concerns with the legitimacy of NGO activities, due to the absence of accountability over the use of funds and other resources. These activists suggested that some NGOs working in the sector prioritise their own interests over those of the individuals and communities they claim to support, meaning they do not help communities to the degree that they should be able to.

Nigerien Activist 2

Some participants reported issues with the management of IOM centres, claiming some migrants were found to ‘use the system’. One Nigerien NGO Director spoke of migrants selling travel tickets bought by NGOs for their return, in order to make money. Another Nigerien NGO president reported how the IOM centre had become almost an 'official ghetto in Agadez', with migrants choosing to stay in the centres during their journey due to the additional support provided to those resident in the centres.

President, Nigerien NGO

Mandarins. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Lack of consideration for local needs

One INGO Migration Coordinator reflected on the years locals have had to struggle without desperately needed development assistance of some kind. She described the indignation felt by locals at the sudden provision of assistance directed solely at the migrant community, despite locals’ very present and pressing needs.

Migration Coordinator, International NGO

The influx of development aid and funds intended to stem the flow of migrants to Europe has catalysed tensions between the host community in Agadez and the migrant populations that have come to reside there (as discussed below).

The President of the Regional Council of Agadez expressed that there had been a severe lack of consultation with Nigeriens and with the region’s leaders on the Agadez council before Law 2015-036 was passed. The Nigerien government took the decision to introduce the law (with the influence of significant EU funds if compliant) without its citizens aware of the law, let alone in agreement with its stipulations.

Niamey to Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

EU activity in the region

After Law 2015-036 law came into effect, authorities began to realise the full impact it had on those previously working in the migration industry. The law criminalised activity that had formed the basis of the livelihoods of many people in Agadez. EU funds were allocated towards a Reconversion Plan, aimed at generating economic alternatives to bolster their prospects. Representatives from INGOs in the region expressed differing - although universally critical - viewpoints on the issue of EU funds, ranging from the corruption associated with the distribution of funds, to the conditionalities attached to EU funds earmarked for preventing migration. Another respondent noted that simply injecting large amounts of money is not a sustainable solution to promote development in the region.

Leaders of INGOs working in the region claimed that mismanagement of development funds in Niger is extreme, with a minute amount believed to reach the people to whom it was destined.

The Deputy Country Director of an INGO expressed his lack of desire to solicit or receive EU funds, since many of the main objectives for EU-granted funds focus solely on preventing migration which does not align with his NGO’s values. Thus, many NGOs likely find themselves in a funding vs. values predicament, forcing them to compromise in some capacity in order to be able to operate.

Deputy Country Director, International NGO

Furthering the notion that receiving EU funds may not have a positive impact, the Deputy Representative of an INGO highlighted potential dangers to the region of having a quick and vast influx of money from top-down institutions like the EU. She described how it could harm the local will for development, since development projects work best when the locals themselves own and manage them, setting development agendas from the ground up.

Deputy Representative, International NGO

She also raised the issue that no amount of money could quickly change mentalities and behaviours within a society that has become accustomed to a certain way of life for so long. As she highlighted, development projects take time, especially when changing mentalities, and if they are hurried simply to provide desirable data to donors in order to justify funds, they are in danger of wasting not only money, but time and effort, ultimately leaving affected communities worse off.

Deputy Representative, International NGO

Passeurs reported how the law had been passed without adequate alternative livelihood solutions in place. Had these already been developed, they could have cushioned the blow felt by the thousands whose livelihood sources were cut off almost overnight. The local Sultan also supported this viewpoint, stating that EU funds were seriously under-allocated, insufficient to assist all those in need:

Sultan de l’Aïr

The general sentiment amongst ex-passeurs and coxeurs regarding the reconversion plan was of frustration and lack of trust of the EU’s promise to direct funds to support alternative livelihoods. Ex-Coxeur 1‘s frustration stemmed from his feeling that the EU had made false promises with regards funds provided for helping those in the smuggling industry leave and find alternatives. He described how money never reached their intended beneficiaries (former passeurs and coxeurs), but instead remains in the hands of those to whom it was not earmarked for, often the central authorities in charge of its distribution. As a result, those previously working in the smuggling industry are left frustrated and desperate with the lack of alternate employment prospects (or financial compensation). They are criminalised and face prison if they continue their trade as passeurs, but this remains the most viable livelihood for many of them to pursue.

Ex-Coxeur 1

However, one possible root cause of the frustration felt may be due to confusion amongst ex-passeurs and coxeurs who were never clearly told how EU funds directed towards the Reconversion Plan would be managed. Many appear to have been under the impression that the money would be handed directly to them to use as they sought fit.

The Director of a Nigerien NGO reported that some ex-passeurs who took part in the EU-funded Reconversion Plan reported not receiving adequate support (financial or otherwise), and thus returned to their former trade as passeurs - this time in secret. Given a lack of economic diversification in Agadez, and the closure of the Djado gold mine in 2017, which had contributed significantly to the local economy, the success of the reconversion scheme is up against significant odds given the underlying political economy of the region. As a passeur, monthly earnings can reach as much as 1 million CFA (about 1,750 USD); for workers employed in the migrant trade, it is nearly impossible to find legal work that offers comparable earnings.

The Activist and President of a Nigerien NGO claimed that the EU funds pumped into Niger had been done thoughtlessly, in a manner that has served to promote corrupt practices.

Activist and President of Nigerien NGO

As the Permanent Secretary of one Nigerien NGO described, the EU’s Reconversion Plan must consult locals – and especially young people – in order to allow them to lead on the economic recovery initiatives that are best suited for their personal ambitions and the good of their communities. If not consulted, the Plan will ultimately neither function and will be unsustainable. Relatively few Nigeriens seek to migrate abroad compared to citizens of other West African states, reinforcing the need for locally-driven development so as to mitigate pull factors that might encourage irregular migration.

Permanent Secretary, Nigerien NGO

Goats. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Chapter 4: Wider impact in the region

Drivers of migration

To understand why Niger is still a major transit country, we need to understand first what drives people to move. Both international and local NGO representatives talked about driving factors for West Africans transiting Niger. A Program Coordinator for a Nigerien NGO referred to two types of migration: the ‘good’ and the ‘bad’. He referred to good migration as the young skilled people who ‘have the right to make their papers, to be in good standing, they can go anywhere in the world’. He described migration for many, as being a last resort; a means of survival and an escape from suffering on a daily basis. For a great number, the decision to migrate is motivated by major frustration and desperation at the lack of opportunities in their home communities.

Program Coordinator, Nigerien NGO

Migration Programs Coordinator, International NGO

In particular, migrants from Sudan now living in Agadez corroborated the abovementioned statement during informal discussions; they described a desperate, future-less situation for them in Agadez in which they are starting to lose hope.

The region has to contend with a myriad of serious concerns: a rapidly increasing population, economic decline, as well as climatic and agricultural challenges posing a threat to those who are simply farming for subsistence.

Deputy Representative, International NGO

Some Nigeriens – the majority of whom come from Zinder, in the south of the country - also make the decision to seek a better future, primarily in Algeria, due to Niger’s worsening economic situation and poor agricultural prospects. An interviewee also reported that he himself now wished to migrate, due to his lack of prospects in the region.

Ex-Passeur

Adedeta. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Economic impact in the region

The migration/smuggling industry brought significant economic revenue to the region, particularly after the decline in the tourism industry. Therefore, after the introduction of Law 2015-036, the economic loss to the region from the law’s passing was significant.

M. Anacko, President of the Regional Council of Agadez

The majority of respondents agreed that the impact of the Law’s passing on Agadez has been negative, largely due to the widespread loss of jobs. Before 2015, migration was the economic driver in the region; every resident in Agadez benefited from it in some way, according to the President of the Regional Council of Agadez, Anacko. The local community has sought to gain acknowledgement from the national government and the European community to re-direct policies to suit local needs. Agadez’s high rate of unemployment, particularly among young people, Anacko said, was exacerbated by the passing of the law, where several thousand were made unemployed. Several ex-passeurs described the contrast in economic circumstances; for one interviewee this now meant an inability to afford basic goods such as food or books for his children.

Passeur

Permanent Secretary, Nigerien NGO

Social impact in the region

Interviewees argued that the reintegrated ex-combatants whose livelihoods have been taken away, now pose a potential security risk to the region. Approximately 7000 ex-combatants initially found work in the industry, and as one ex-passeur explained; just as ex-combatants and those working in the tourism industry turned to the migration industry as an alternative, the obstruction of the migration industry requires alternatives for those involved:

Ex-Passeur

M. Anacko also admitted that the criminalisation of the industry and the lack of alternatives is likely to push people into illicit activities such as trafficking and terrorism - something that young people were particularly vulnerable to.

M. Anacko, President of the Regional Council of Agadez

The Nurse also supported this idea by saying that while some of the practices that have been carried out by ex-smugglers as a result of unemployment are unacceptable, such as stealing, these activities are a reflection of the desperate situations many are now in; unable to afford food to eat. Involvement in other illicit activities has also reportedly increased due to this. The Sultan de l‘Aïr believes that:

Sultan de l’Aïr

Consequently, tensions between migrants and locals have risen significantly, with a number of respondents reporting negative feelings towards migrants, and others foreseeing a high potential for future conflict. This is unsurprising, considering the added strain of supporting migrants in an already under-resourced region, in a country experiencing significant population growth.

Deputy Country Director, International NGO

Some locals interviewed were critical of migrants’ behaviour, with one reporting an increase in sexual harassment, while others reported general 'disrespectful’ behaviour.

Nigerien Activist 1

Others felt resentment towards the migrant population, due to the favoured treatment some NGOs reportedly show to migrants over locals. One Nigerien nurse expressed exasperation at the negative consequences of their presence. Many locals find it difficult to see any benefit to migrants’ presence, with some reporting that it has direct negative implications on locals’ situations:

Nurse

According to one International NGO’s Migration Coordinator, a lot of Nigerien locals at various levels of society feel frustration at the lack of positive outcomes for them despite the large financial injection to the region:

Migration Coordinator, International NGO

Nigerien Activist 1 talked of the importance of creating a strategy of reconciliation between populations and local development, where the interests of both groups are taken into consideration. Investment in specific sectors, benefitting migrants and locals alike, is part of the solution to aid the region while bringing about reconciliation so that locals don’t feel indignant due to neglect. He claimed that NGOs are largely responsible for the tension and mistrust felt between locals and migrants. He highlighted the importance of investment in the region’s social security, with health and education as top priorities, followed by security including the regional stabilisation concerns and food security. He takes this further and argues that Niger, and the Sahel need a ‘strategic development for security’, which combines ‘security and development’ through sustainable development and inclusive growth.

Security challenges

Interviewees reported that the migration industry and terrorism were interlinked to some degree. Some interviewees suggested that smugglers had been very active in unofficial, but highly effective, counter-terrorism operations in the region. The President of the Regional Council of Agadez highlighted the importance that those working in the smuggling industry, navigating the desert, played in the security and stability of the region.

M. Anacko, President of the Regional Council of Agadez

Therefore, as a result of the criminalisation of people smuggling, regional counterterrorism efforts have lost a vital source of intelligence.

Many interviewees noted the country’s current security challenges, particularly from terrorist activity in regions such as Diffa, where Boko Haram is a very present threat. One ex-passeur claimed that Boko Haram’s activity in this region was in fact conducted by locals of the region.

The President of the Regional Council of Agadez expressed the potential terrorism challenges Europe may face in the future, due to the current downward pressure the migration industry is currently facing. In his opinion, if local young people are left in desperate situations with few alternatives, they may feel that engaging in terrorist actions is their best option. As a result, further in the future, Europe could face terrorist threats or attacks, which stem from policies the EU itself created. The short-sightedness of current EU policies, he said, may create graver problems which, while distant right now, may in the future have a direct impact on European societies.

Goats and motorcycles. Agadez - ©️ Xchange Foundation/Ioannis Papasilekas - 2018

Chapter 5: Vision for the future

Interviewees reported a range of concerns and ideas for the region’s prospects. Some talked optimistically and others negatively about Agadez’s future. Some mentioned tourism as a potential industry to re-develop in order to boost the economy, as this worked successfully during Agadez’s more stable past. Others expressed the need for locals to take ownership over the direction of the region’s future development. The region’s security concerns were mentioned by some as risks and challenges requiring management alongside any future solution.

Local ownership of regional development

Some participants working locally highlighted the importance of locals taking ownership of the region’s development for the future. A local nurse believed that locals have to be the actors leading and managing the region’s future, taking decisions over the industries and resources Agadez requires.

Nurse

A local NGO Permanent Secretary echoed her point of view, stating that his NGO’s approach, and the approach he thinks the region needs, is to work with young people to be fully involved in managing the public issues of the region, alongside other stakeholders and governing officials. In turn, he claimed this will help tackle the frustration many young people experience due to the lack of opportunities or consultation in the region, which may cause them to migrate in search of greater prospects. As a result, this strategy would also help deal with one of the potential drivers of local Nigerien migration in the future, as Niger’s young people continue living in a country offering them very little incentive to remain.

Sultan's palace of Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Tourism

Several community and NGO leaders spoke of tourism as one of the main prospects of hope for the region. One International NGO’s Migration Coordinator expressed heartfelt sentiment towards Agadez, acknowledging the numerous and complex challenges that the region faces in its development trajectory, yet described how Agadez isn’t just a region marred with problems. She described how ‘the warmth and the joy of this region, and its people, really is palpable’, yet unfortunately all the international community sees of Agadez is a region of diminishing opportunities and stability.

Migration Coordinator, International NGO

Another NGO representative (Director, Nigerien NGO) shared a similar opinion, that tourism was one of the main keys for Niger’s future development. He even suggested that projects within the tourism sector could be part of the programme to provide alternative livelihoods to ex-smugglers. However, he acknowledged that in order for tourism to become a popular industry in the region again, serious efforts will need to be made to improve regional security wider.

Concerns for the region’s future

Many influential actors including NGO leaders and community leaders mentioned the region’s instability when describing tourism as a past or future prospect. Thus, the tourism industry cannot simply receive an injection of funds to develop businesses. A comprehensive solution must also involve addressing the region’s large-scale and imminent security concerns. In order for the tourism industry to re-emerge and become a strong economic catalyst once more, serious transformation and management is required in terms of the region’s security and stability situation.

Director, Nigerien NGO

Moreover, even without tourism as a strategic focus specifically for economic development, the region’s general future remains precarious and unpredictable, due to the various political, economic and security challenges the region has to contend with. In terms of security risks, the region suffers from the continued threat of rebellion, violent extremism, and instability caused by other groups. This requires not just effort from Niger’s national and local governments, but also combined efforts from the Nigerien state calling on international organisations to commit to strengthening the area’s security efforts together.

Director, Nigerien NGO

An additional concern expressed by a Deputy Representative of an International NGO working in the region, was of the population-resources constraint the country as a whole suffers from. Niger has the world’s highest fertility rate, and experiences annual population growth at a rate of almost 4%. The representative stressed the seriousness and urgency of this demographic crisis, which together with the country’s situation of limited resources, puts immense strain on public goods and services, rendering them overstretched and unable to meet all needs. In addition, he explained how Niger’s low levels of health and education present further drains on state services. To try to provide for both the expanding population, low levels of education, and limited public goods, in his opinion, the country needs an industry boost, in order to get the economy generating positive economic growth again. However, since this hinges on Niger’s workforce, he suggests that the priority should be to invest money in human capital. Investment is necessary to provide education and training to create a skilled workforce, he explained, that can engage in economic activity. Despite this, he also acknowledged the need for serious change in behaviours and culture, to tackle the country’s population growth that presents such a drain on the country’s already limited economy and resources.

Deputy Representative, International NGO

Conclusion

The introduction of the Law 2015-036 by the Nigerian government had colossal consequences for migration in the region. As this report has presented, the migration industry became criminalised in response to the aforementioned legislation, which has resulted in a clandestine industry and increased risks for migrants and smugglers. EU pressure over border management has been depicted as a key influence in the government's decision to put an end to migration, thereby contradicting ECOWAS' provision for Freedom of Movement.

Migration is still present in the region, though it has changed form. Smugglers are now transporting migrants through non-traditional routes, putting at risk their lives and those of the migrants being transported. Transnational movement now takes place through routes that are longer and more hazardous. Migrant deaths are less widely reported than they used to be, with many interviewees attesting that migrants are now much more likely to go missing or be left to die, in response to higher securitisation of the areas surrounding Agadez.

Nigerien Activist 1

Locals tended to feel that their needs and opinions were not consulted or prioritised with regards to the passing of the 2015 anti-migration law, and with the economic recovery activities proposed for the region. Mistrust towards INGOs and other actors operating in the country and disillusionment with their activities was a major issue reported by participants. The EU’s Reconversion Plan was widely criticised as being unfruitful, with the mismanagement of funds being a significant cause of this.

Activist and President of Nigerien NGO

The passing of Law 2015-036 and criminalisation of smuggling-related activity has led to serious economic and social consequences within Agadez – the loss of livelihoods for thousands of people being the most obvious. The region now has a multitude of issues to contend with, including vast unemployment, a growing population desperate for alternatives, and rising tensions between local and migrant communities. In addition, serious security challenges including terrorist activity appear to be an ever-increasing threat to the nation - and beyond - as the lack of alternative livelihoods has been reported as a risk factor for radicalisation.

Migration Programs Coordinator, International NGO

It seems clear that part of the problem is the top-down approach to the decision-making and implementation of the region’s policies and development aims. Locals must be consulted, informed and involved in any decisions surrounding Agadez’s future development. Several respondents pointed to tourism as one of the region’s greatest hopes for the future, yet acknowledged the major challenges present in the region, not least the potential for instability.

Businessman, Agadez

Sunset on Niger River - ©️ Xchange Foundation/Maria Jones - 2018

Key Concepts and Definitions

Asylum seeker

Acknowledgements

Data Collection, Research & Analysis: Ioannis Papasilekas

Data Collection, Research & Analysis: Maria Jones

Research & Analysis: Maria Fatas Ortega

Research & Analysis: Anna Skinner

Project funded by moas.eu

Contact Us

As an information and research initiative, we are eager to work with a wide spectrum of stakeholders to exchange information and knowledge.

We are looking for partners and funding organizations to support us in conducting a new round of surveys. Please, feel free to send us your proposals.

Copyright © Xchange.org 2017