“We do not believe Myanmar!”

In March 2019, Xchange returned to Bangladesh to conduct a survey with Rohingya refugees living in protracted displacement. - This is what we found.

Introduction

The Rohingya have been fleeing persecution and ethnic cleansing since escalating waves of violence against the Rohingya people started in Myanmar in the 1970s; entire families started fleeing to neighbouring Bangladesh in search of protection. Despite their presence in Myanmar dating back to the seventh century, the Government of Myanmar continues to deny the Rohingya their most basic human rights. This marginalisation and denial of rights was enshrined and legitimised through the introduction of the 1982 Citizenship Law. The Law introduced unobtainable and unrealistic requirements for minority groups, like the Rohingya, to be able to claim formal citizenship - thereby de facto excluding them the chance to be recognised as equal citizens. As one of the largest stateless populations in the world, their access to employment, education and healthcare, as well as movement within Myanmar, is fraught with extreme difficulty.

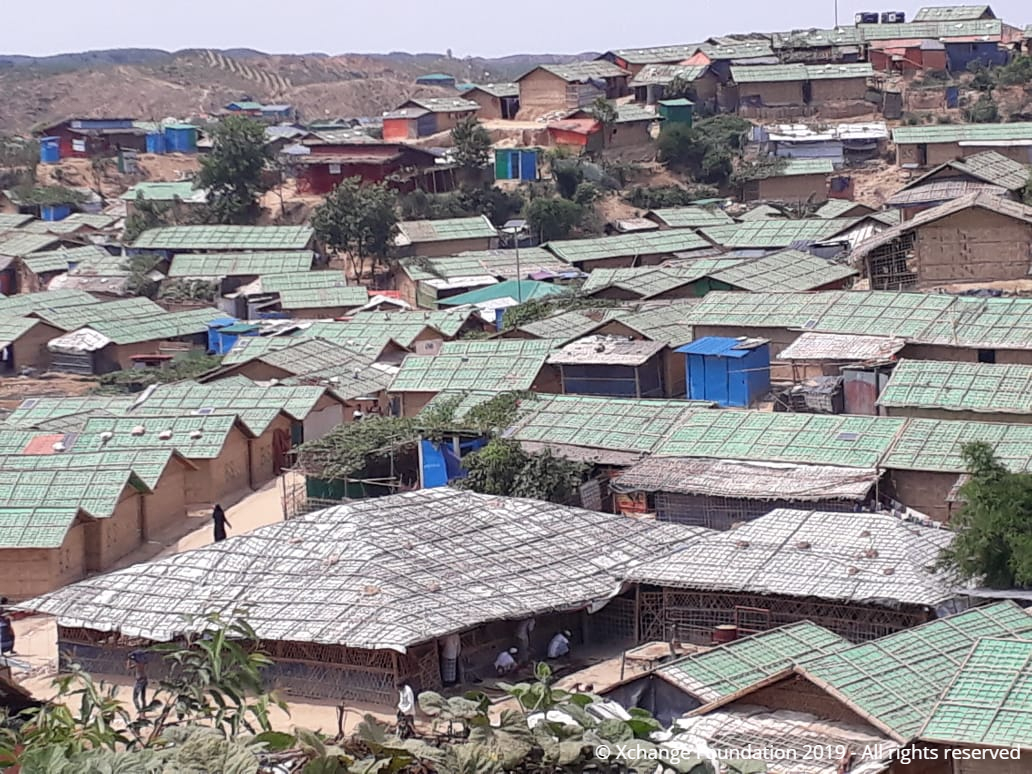

The most recent wave of violence hit the Rohingya in August 2017 when the Myanmar military began a disproportionate and indiscriminate campaign of ethnic cleaning which saw 745,000 Rohingya – most of whom were children – seek safety in neighbouring Bangladesh. Today, there are nearly a million Rohingya living in temporary camps in the Cox’s Bazar district of Bangladesh. For many Rohingya born and raised in the camps, Bangladesh is all they know. Despite this, Bangladesh considers Rohingya as “illegal immigrants”, instead of refugees, and subsequently their access to basic human rights, such access to education, employment or freedom of movement, are severely restricted.

Nineteen months after the mass exodus in August 2017 the situation on the ground is moving from humanitarian disaster to a crisis of protracted displacement for the hundreds of thousands of Rohingya that arrived since then, bringing with it new and pressing concerns. As such, Xchange decided to return to Bangladesh for a sixth time to speak first-hand to the newly arrived Rohingya awaiting solutions.

This report aims to understand how the situation has changed since the peak in arrivals in 2017, by building on the topics of our previous surveys, as well as identifying new concerns and areas of focus. We aim to provide statistical substance to what has historically been opaque due to the discrimination and isolation experienced by the Rohingya community, thereby contributing to better informed policy creation.

Camp 4

Methodology & Research Implementation

Objective

The objective of this project was to provide an assessment of the situation in Rohingya refugee camps from the perspective of adult Rohingya Muslims that had arrived in Bangladesh after the August 25th2017 military operation in northern Rakhine State. Moreover, we sought to identify the Rohingya’s social connections, coping mechanisms, opinions about the proposed Rohingya relocation to Bhasan Char island, and their plans for the future.

Research Design & Data Collection

This report is informed by a cross-sectional survey with 1,277 Rohingya refugees which was conducted over a three-week period (March-April 2019) in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

The data collection team consisted of four enumerators, three men and one woman, all Rohingya refugees themselves and fluent in the Rohingya language. The enumerators administered questionnaires with the use of a mobile data collection application at Kutupalong, Balukhali, Thangkhali, Hakimpara, and Shamlapur refugee settlements in Cox’s Bazar district, Bangladesh.

Camp 14

The survey design was based on Xchange’s previous reports, literature reviews, and key informant interviews. The research instrument included questions based on Likert scale responses, closed-ended questions (yes/no), open-ended questions, and multiple-choice questions. The answers to the open-ended questions were translated by the enumerators from Rohingya to English on the spot. Prior to data collection, a pilot test of the research instrument was conducted in Shamlapur (Camp 23). Minor changes were made to the questionnaire to facilitate the respondents’ understanding and reduce any potential response bias.

Each enumerator interviewed an average of 17 people each day, whilst maintaining constant remote communication with the Xchange research team and receiving guidance from a local facilitator on the ground. All surveys were conducted in person and in a secluded area to ensure privacy, when feasible. The principle of anonymity was explained to all respondents and verbal consent was ensured before proceeding with the survey.

To establish a high level of rapport between interviewers and interviewees and ensure the information received was as unbiased as possible, the female enumerator interviewed only women. The male enumerators interviewed a predetermined number of women and were responsible for interviewing all male respondents. At the end of each working day, the surveys were immediately uploaded to an online platform for review by the coordination team and to avoid data loss.

Target Population & Sampling

The researchers employed a quota sampling technique. The underlying target population was estimated to be 283,937 adults (over 18 years old), ‘new’ Rohingya (those who had arrived in Bangladesh after the events of 25 August 2017) and currently residing in refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar district. This number was determined through simple calculations based on the most current data available from the UNHCR (15 March 2019) at the time of data collection preparation. The target sample was 1,300 new adult Rohingya. The data provided by the UNHCR allowed the researchers to establish the population and gender distribution for each refugee camp, and thus choose the number of respondents to include in the survey from each camp proportionately. Each subgroup within the target population received representation within the sample and no subpopulation was overrepresented in the results.

Map of data collection - © Xchange.org 2019

Out of a total of 1,455 surveys conducted, 1,277 were deemed sufficient for further analysis. The sample of 1,277 respondents can be considered broadly representative of the total adult, new Rohingya population residing in the selected refugee camps across Cox’s Bazar district.

Limitations

The enumerators were given instructions to select respondents randomly in the chosen camps which was not always possible for several reasons. Hence, even though the sample can be considered representative of the population under study, the potential for selection bias cannot be excluded.

The enumerators, as Rohingya refugees themselves and fluent in Rohingya, could clarify questions posed by the respondents. However, the questions and the responses were translated from English to Rohingya and from Rohingya to English respectively by each enumerator on the spot. This might have resulted in misinterpretations and/or negatively influenced the accuracy of some responses.

Data regarding the respondents’ views of Rohingya involvement in illegal activities, substance use as a coping mechanism, and of violence in the camps should be interpreted with caution because of the potential for bias due to respondents trying to preserve the image of their community with regards to these sensitive topics.

Camp 7

Sample Description - Demographics

Sex & Age

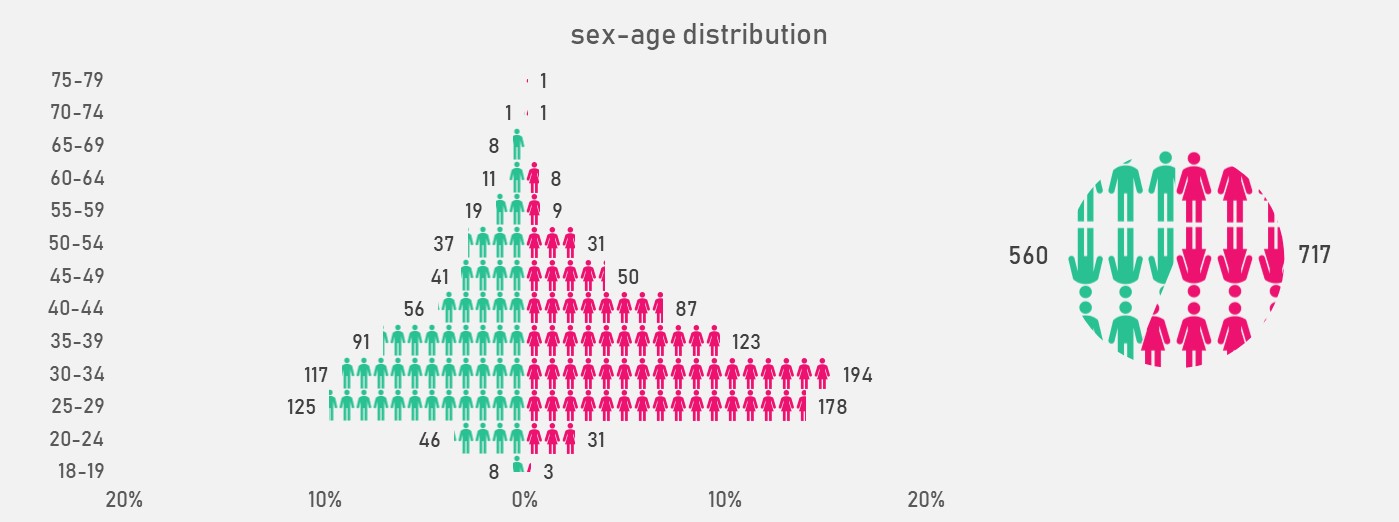

Sex and Age distribution - © Xchange.org 2019

The sample comprised of 1,277 Rohingya adults: 717 females (56%) and 560 males (44%). The respondents’ ages ranged from 18 to 75 years, with a median of 32 years. The age groups that were more represented were the 25-29 group and the 30-34 group (23.8% and 24.4% of the total sample, respectively). More than half of the female respondents were between 25 and 34 years of age. 67% of respondents above the age of 55 were males.

Arrival in Bangladesh & Residence

Almost all respondents arrived in Bangladesh in late 2017: 11% arrived in August, 55% in September, 31% in October, and 3% in November and December of the same year combined. At the time the survey took place, the respondents resided in camps within the Kutupalong-Balukhali mega-camp, Hakimpara, Jamtoli, and Shamlapur. The number of respondents from each camp can be seen below:

Camp of residence - © Xchange.org 2019

Six in ten respondents (60%) were heads of households. By sex, relatively more males (92% of all males interviewed) than females (35% of all females) were heads of households.

Family Situation

Eight in ten respondents (81%) were married at the time of the survey. More than one in four females were either widowed or divorced. 23% of females were widowed compared to just 1.5% of males.

Out of 1143 respondents, 90 (or 8%) did not have any children under 18 , 66 (or 6%) had only one child under 18, 790 (or 69%) had between two and four children under 18, and 197 (or 17%) had five or more children under 18. Of those who did not have any children under 18, seven in ten respondents were male.

97% of respondents reported that they did not have a disability.

Education

Highest level of education - © Xchange.org 2019

Almost half (48%) of respondents had not received any education. Four in ten women had just received informal schooling, possibly only until a very young age, as anecdotal evidence supports that girls stop going to madrasas around 12 or 13. Only one in ten females had a primary education compared to two in ten males. One in ten males had graduated from secondary education. Just three respondents (all males) made it to university.

Occupation & Employment

The vast majority of respondents (88%) were not employed at the time of the survey, which was expected as Rohingya are not allowed to leave or work outside the camps, let alone be formally employed. Of the remaining 159 respondents (or 12%), more than half (57%) were volunteers (in e.g. WASH, outreach programmes, healthcare, and hygiene projects) for more than 25 NGOs operating in the area, ten were shopkeepers, four were day labourers, five were tailors, 39 were teachers either in madrasas or NGO-run education centres , and four were security guards. Moreover, included in the sample were five males who were occupied as majhis ( without renumeration).

Camp 8E

Findings

Evaluation of life in the refugee camps

Level of satisfaction with... - © Xchange.org 2019

One of the objectives of the survey was to identify the level of satisfaction of the Rohingya in camps, through the evaluation of several components considered to play a role on daily life within the camps.

Four in ten Rohingya were satisfied with the amount of space allocated to them and their families within the camp, while six in ten were either unsatisfied or very unsatisfied. On the other hand, despite the camps’ severe overcrowding, 93% of respondents believed that the level of hygiene in the camps stands at a satisfactory level, with respondents stating that sanitation improvements have taken place in the camps in the last months, e.g. raised awareness of hygiene and the building of tube-wells and public toilets.

26-year-old Rohingya male

33-year-old Rohingya female

Camp 11

However, there were several who believed there is still room for improvement:

35-year-old Rohingya female

33-year-old Rohingya female

The majority of respondents were either unsatisfied or very unsatisfied with both the lack of job opportunities available to them (80%) and the income their families made (92%).

30-year-old Rohingya female

Camp 4

97% of new adult Rohingya living in the chosen camps felt either satisfied or very satisfied with the overall help they had been receiving from the NGOs operating in their area.

Camp 19

97% of Rohingya respondents stated that there are enough healthcare facilities in the area that they live (e.g. aid stations, hospitals, health centres) that they can access. However, only two in ten Rohingya were satisfied with the quality of healthcare they had been receiving, while 78% agreed that there is room for improvement.

40-year-old Rohingya female

Whilst the majority were satisfied (52%) or very satisfied (21%) with the level of social support they had been receiving from neighbours, friends, and families, 86% of Rohingya identified a lack in psychological support offered by specialist providers within the camps.

Camp 1E

Camp 1E

As for the quality of education, not many respondents identified that they were very satisfied or very unsatisfied. Four in ten were satisfied but the majority (six in ten) were unsatisfied:

50-year-old Rohingya male

Educational opportunities - © Xchange.org 2019

Camp 7

More than 99% of Rohingya agreed that there were enough educational opportunities for Rohingya children below the age of 12, but that provision was inadequate for adolescents and adults, with more than 99% agreeing that there were not enough educational opportunities or higher education for adolescents or adults.

19-year-old Rohingya male

30-year-old Rohingya male

Overall, the highest level of satisfaction was found on the number of religious facilities in the camps, where Rohingya almost unanimously (99%) agreed that there are enough madrasas and mosques within their communities. This finding correlates with the fact that 99.8% of the sample believed that they can exercise their religion freely in the camps.

Situation in the camp - © Xchange.org 2019

The respondents were also asked to compare the overall situation in the camps ‘now’ to how it was ‘six months ago’. Overall, 69% believed that nothing had changed.

28-year-old Rohingya female

On the other hand, there were many who have seen improvements in this time; 30% believed that at the time of the survey the situation was better than six months prior for several reasons:

26-year-old Rohingya female

27-year-old Rohingya female

50-year-old Rohingya male

30-year-old Rohingya male

22-year-old Rohingya male

No male respondent preferred the life they lived half a year ago compared to 14 females who did.

28-year-old Rohingya female

26-year-old Rohingya female

Feeling at home - © Xchange.org 2019

To conclude this section, almost half (47%) of the Rohingya we interviewed did not feel at home at all in the camp in Bangladesh. Four in ten (41%) felt at home very little, while one in ten (11%), the majority female, felt somewhat at home in the camps. Just five out of 1277 Rohingya felt at home to a great extent.

Camp 4

Violence, sexual harassment, and missing children

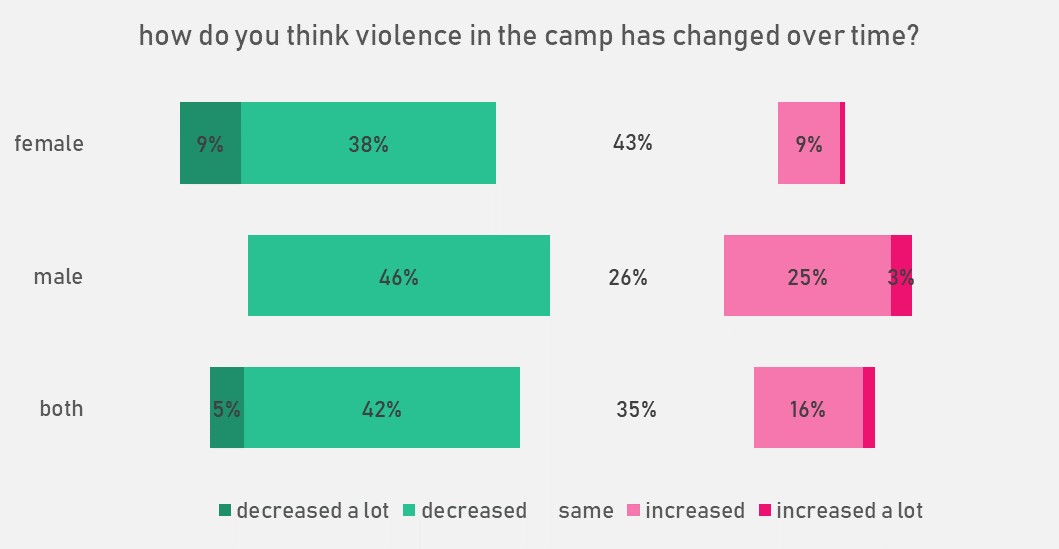

Violence in the camps - © Xchange.org 2019

One in three respondents (35%) believed that the level of existing violence in the camps had not changed over time. 47% of respondents believed that violence in the camps had either decreased (42%) or decreased a lot (5%) due to the increased level of security within the camps.

28-year-old Rohingya female

32-year-old Rohingya female

18% of respondents believed that violence had increased with a few identifying that it had increased a lot. There were differences observed between camps, with camps 14 and 15 having the highest relative numbers of respondents identifying that violence has increased, with 61% and 68% of respondents respectively.

40-year-old Rohingya female

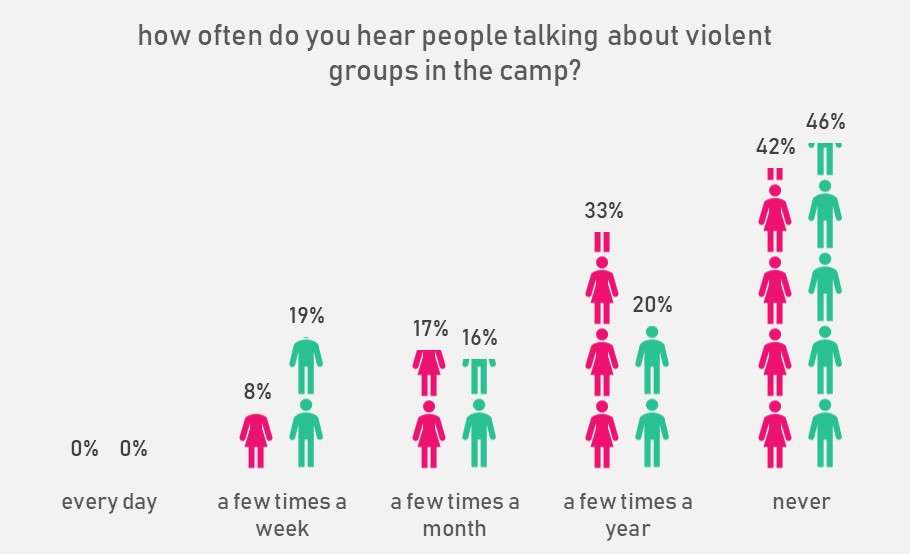

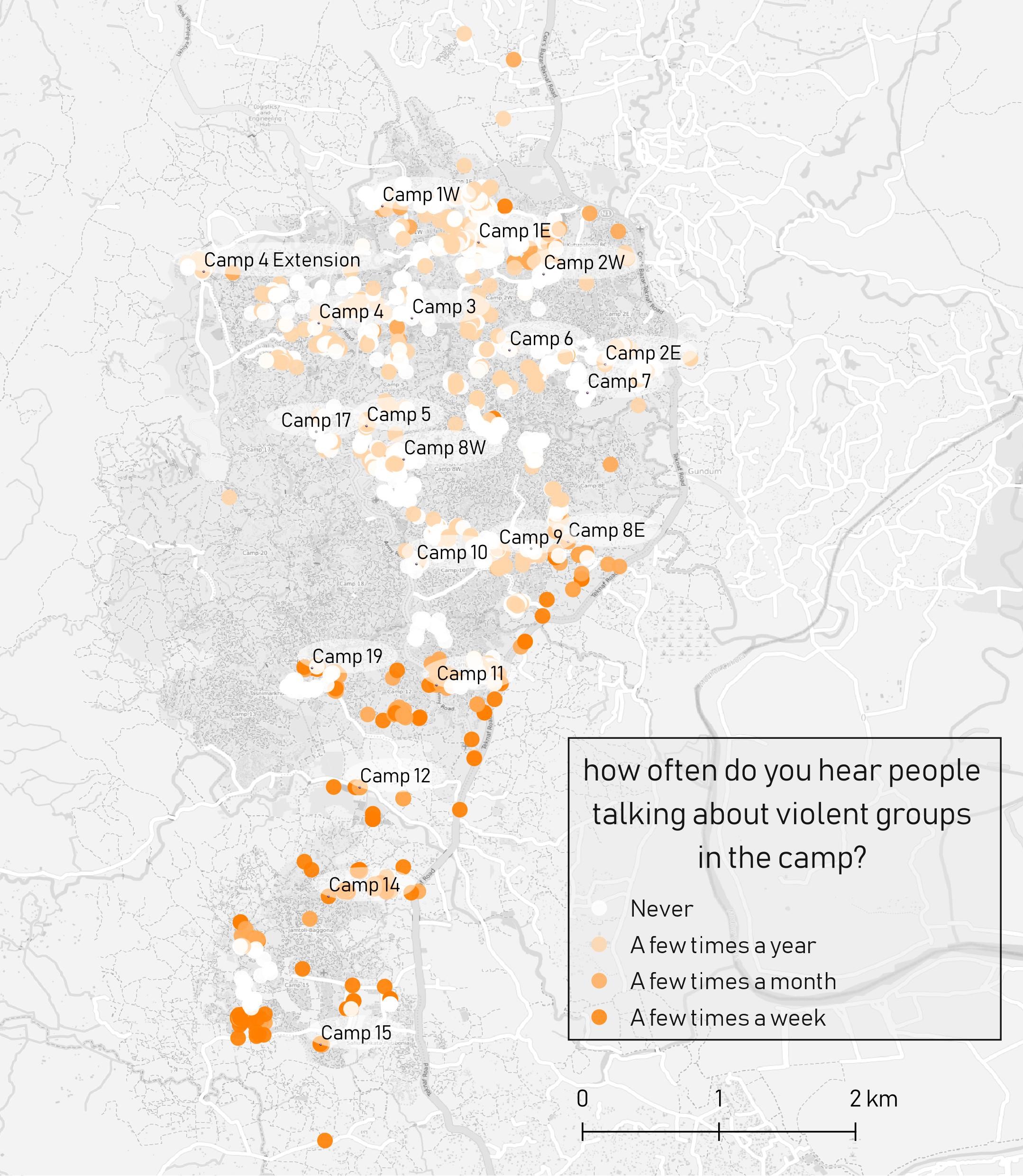

Talks about violent groups in the camps - © Xchange.org 2019

44% of respondents had never heard people talk about violent groups operating in the camps. More than one in four Rohingya adults, however, had heard people talking about violent groups in the camps at least a few times a month. Spatial analysis showed that the highest concentration of identified cases where violent groups had been mentioned took place mostly in the southern mega-camp areas and those closer to the Cox’s Bazar-Teknaf highway.

Map showing the frequency of Rohingya hearing about violent groups operating in refugee camps - © Xchange.org 2019

Camp 15

More than one in four adult Rohingya, with an equal representation of male and female respondents, believed that sexual harassment was prevalent within their camps according to their own understandings of what harassment is. There was a 5% non-response rate to this question. Of those who believed that sexual harassment did take place, 79.8% stated that it mostly happened in the streets and 19.7% thought that it was most likely to occur in the market. Just one female stated that it happened in the household.

Nine in ten Rohingya adults interviewed (91%) believed that there were Rohingya families in the camps who had a child that had gone missing since they had moved to the refugee camp, showing a high level of awareness of child trafficking amongst Rohingya adults. This finding explains why 86% of Rohingya parents of children under 18 supported that they were very afraid and 13% were quite afraid to leave their children unattended after dark. However, just 1.3% of respondents knew on a personal level a family who had lost their child.

32-year-old Rohingya female

30-year-old Rohingya male

19-year-old Rohingya male

32-year-old Rohingya female

42-year-old Rohingya female

20-year-old Rohingya female

There were only just a few respondents who had an idea of where the child in question was:

50-year-old Rohingya male

Camp 10

Information Access

Information sources - © Xchange.org 2019

We sought to identify what sources are used by the Rohingya to get news and information about current events. Supporting the findings of our previous surveys, the majority of female respondents relied on the word of mouth, with 95% of female respondents stating that they would hear the news from either friends and neighbours or family members - generally their husbands. On the other hand, almost four in ten males rely on social media for their information gathering. More traditional methods of news acquisition, such as radio and newspapers, were found to be the main information providers for just a few individuals. Television and NGO workers were not found to be the main information source for anyone.

Camp 12

Social Hierarchy

Another objective of the survey was to identify what the relationship was between Rohingya camp residents and Rohingya who hold a certain level of power within camps, such as community or religious leaders, in an attempt to identify camp social hierarchy. Here, there were no significant differences observed between the two sexes; both males and females considered their block’s majhi (46% of the sample), the Camp-in-Charge officials (28%), and the head majhis (24%) as the most important person. A few female respondents considered a family member as the most important person, in particular, their parents or husbands.

Camp 6

Camp 7

Rohingya interviewees were also asked to identify one or two people, other than family members, that they could turn to when they needed help to solve an everyday problem. This was done in an effort to identify their existing social support system, as well as highlighting any potential dependencies or vulnerabilities. The majority of respondents (876) identified that they would go to the block’s majhi for help, 326 to the head majhi, whilst the third most popular choice were neighbours (34). 30 respondents mentioned asking for help from the army soldiers appointed in the camps, 11 from the CiC, and just eight considered asking for help from the imam or religious elders.

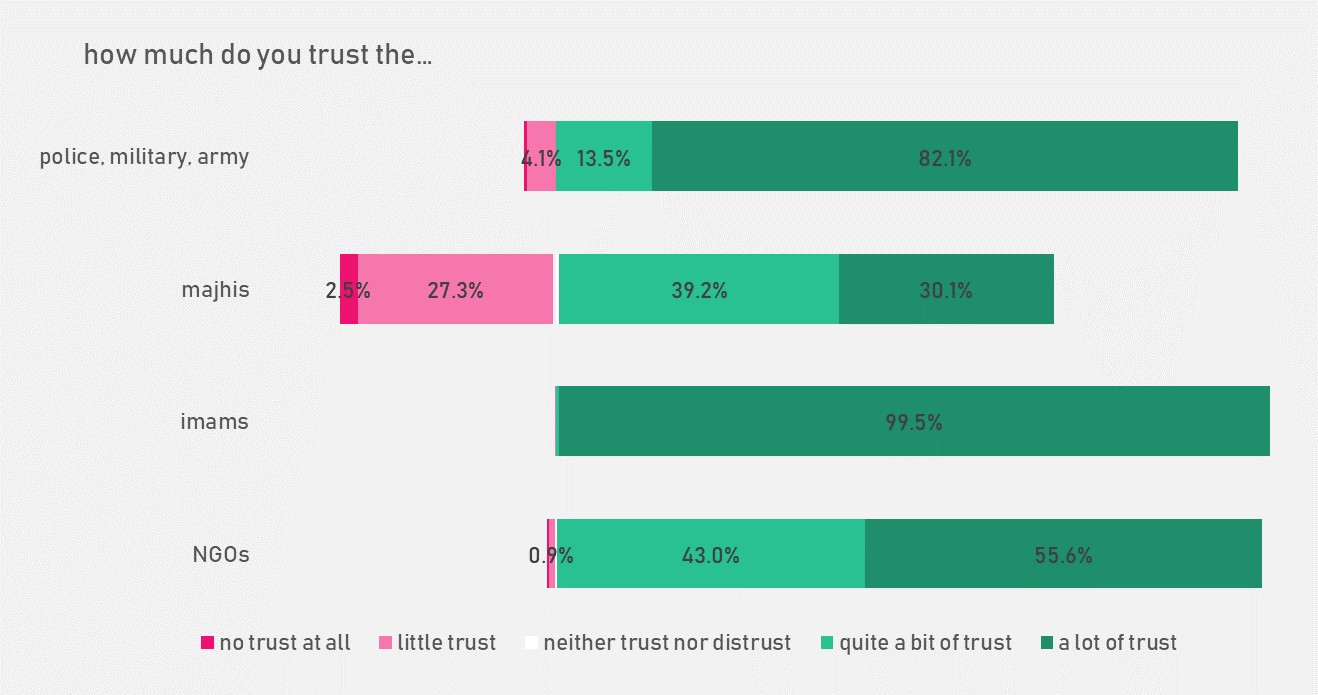

Trust - © Xchange.org 2019

On the other hand, even though the majority of individual refugees asked for help from the majhis, trust in them appeared to be a challenging issue, with almost one in three Rohingya having little to no trust in majhis. The Rohingya almost in their entirety (99.5%) had complete trust in the religious leaders-imams in the camps. Moreover, the vast majority had a lot of trust in the police, military, and guards of the camps (82%). Respondents were divided into those who fully trusted NGOs (56%) and those who had quite a bit of trust (43%), with only a few individuals having little or no trust at all. Respondents also supported that they felt either comfortable enough (75%) or very comfortable (20%) sharing their problems with NGO workers.

Talking to NGO workers - © Xchange.org 2019

Camp 6

Social Connectedness

97% of respondents felt they had plenty of good friends in the camp and more than half (53%), proportionally more males than females, considered having at least one Bangladeshi person as their friends. Despite this relatively low proportion, almost all (97%) Rohingya adults we interviewed believed that Rohingya and Bangladeshis ‘can be good friends’, signifying a strong will for integration within the local Bangladeshi community.

However, just a few individuals believed that intermarriage between Rohingya girls or women and Bangladeshi boys or men takes place nowadays. Only three respondents admitted knowing on a personal level a family which had married their daughter off to a Bangladeshi boy. Informal discussions with Rohingya suggested that this phenomenon mostly belongs to the past.

Connections with Rohingya abroad - © Xchange.org 2019

Two in three males (66%) and one in three females (34%), or almost half (48%) of those interviewed, stated that they talk with other Rohingya outside Bangladesh and Myanmar at least once a month. Of those who do keep in touch with other Rohingya abroad, 65% have contacts in Malaysia, 31% in Saudi Arabia, 4% in India, 3% in Australia, and 1% in the UAE, USA, and Oman. Only six out of 1,277 respondents were in contact with people who were not Rohingya outside Bangladesh and Myanmar, in particular in the Netherlands.

Camp 6

Coping Mechanisms

98% of respondents identified they often felt stressed or overwhelmed by their living situation. 89% maintained that ‘talking’ about their everyday problems made them feel better than ‘trying to forget’, while the other 11% preferred the latter.

Moreover, 95% of the Rohingya preferred to ask for the help of others than to solve their problems alone. This finding shows how maintaining meaningful relationships with others is of great importance for the Rohingya. In proportion, more females (6.7%) than males (3.4%) did not ask for others’ help. 81% of Rohingya felt that sharing their concerns with others made them feel better than keeping them to themselves; relatively more males (85%) than females (78%) felt like this, possibly because males are more connected in the camps, whilst females are more likely to stay at home.

Camp 4

To identify the ways in which Rohingya escape their difficult realities, they were asked as to whether they engaged in certain habits such as smoking or chewing betel nuts. 20% of respondents were cigarette smokers at the time of the study, 1% of females and 44% of males. On average, Rohingya smokers smoked 9 cigarettes a day. 12% (all males) of smokers smoked more than a packet of cigarettes (20) a day. However, 22% of current smokers had not smoked in Myanmar prior to moving to Bangladesh, a finding that could be an outcome of the overwhelming situation that they were living in in at the time of the survey.

58% of respondents (69% of males and 49% of females) chewed betel nuts; with 14%of those who did, chewing more than 15 nuts per day. On average, Rohingya chewed eight (7 for females and 9 for males) betel nuts a day. Just 2% of Rohingya started chewing in Bangladesh, while the rest had already been chewing in Myanmar.

Overall, 37% of Rohingya adults were neither smokers nor chewed betel nuts (18% of males, 51% of females). 14% both smoked and chewed (31% of males, 0.8% of females).

Camp 11

Regarding other substances, 21 female respondents (3% of females) and one male respondent believed that there were Rohingya in the camps who drank syrup and medicines often without needing them, with 50% of those admitting to either having witnessed or experienced it themselves. 56 (or 4%) did not wish to reply to this question; with more females (6%) than males (2%) unwilling to reply. Some identified that some women had made drinking syrup their ‘habit’.

30-year-old Rohingya female

52-year-old Rohingya female

29-year-old Rohingya female

93% of respondents thought that alcohol consumption, illegal drug or substance use did not occur in the camps. 6% did not reply to the question, while only eight individuals (or fewer than 1%) thought that alcohol and drug use occurred in the camps, of which just two females admitted to either using themselves or coming into direct contact with users of alcohol or drugs.

Male respondents maintained that Rohingya could not have been involved in illegal activities such as drug trading (yaba) or alcohol trafficking or illegal selling. However, 34 female respondents (5%) believed that it occurs.

55-year-old Rohingya female

32-year-old Rohingya female

The non-response rate to this question was higher than any other question in the survey with 14% of respondents (19% of females, 7% of males) not commenting at all on the matter.

Camp 8W

Relocation & the Future

98.7% of respondents were informed about the plans of the Bangladeshi government to relocate Rohingya from Cox’s Bazar district to Bhasan Char, a silt island further north in the Bay of Bengal. Only 1.6% of those interviewed however would consider moving to Bhasan Char. 98.4% categorically refused to consider going, for two main reasons: fear of their safety on the island and not wanting to move further away from their homeland, Myanmar.

28-year-old Rohingya male

25-year-old Rohingya female

32-year-old Rohingya male

40-year-old Rohingya female

42-year-old Rohingya female

Camp 12

Several respondents identified that proximity to their native land is very important and this limits their willingness to be relocated to another site, further away from Myanmar.

20-year-old Rohingya female

48-year-old Rohingya female

45-year-old Rohingya male

60-year-old Rohingya male

28-year-old Rohingya male

Respondents were also asked to give their opinion on whether they believe that the Government of Myanmar will recognize the Rohingya as citizens and provide them with citizenship rights in the next two years. 69% of respondents were pessimistic; with more females (73%) than males (63%) having negative feelings. This question yielded the exact same results in a previous Xchange survey (Repatriation Survey).

21-year-old Rohingya female

25-year-old Rohingya male

30-year-old Rohingya male

32-year-old Rohingya male

42-year-old Rohingya female

30-year-old Rohingya female

48-year-old Rohingya male

27-year-old Rohingya male

In the event that the Myanmar Government would provide the Rohingya with their rights in the next two years, the majority of the Rohingya would consider repatriation; with 93% of respondents saying that they would return to Myanmar. Disaggregated by sex however, even though males almost unanimously (99.8%) agreed to considering repatriation, females were more reluctant, with 13% no longer considering repatriation. This finding agrees with the fact that relatively fewer females (22%) believed that repatriation will happen in the next two years than males (34%).

Overall, 73% of Rohingya did not think that repatriation will happen in two years’ time. This finding is quite different from the one in Xchange’s Repatriation Survey, where to the same question, the majority, or 78%, thought repatriation would take place in the next two years. Rohingya have become less optimistic over time.

29-year-old Rohingya male

27-year-old Rohingya male

Where will you be in six months? - © Xchange.org 2019

Respondents were asked to imagine where they will be in six months from the time the survey took place, which corresponds to the end of the 2019 monsoon season. Several aspired to the idea of living in a place where they felt safe and respected, including returning to Myanmar.

33-year-old Rohingya female

25-year-old Rohingya female

Camp 8W

However, the vast majority was confident they would still be residing in their current refugee camp.

30-year-old Rohingya male

20-year-old Rohingya male

24-year-old Rohingya male

Potential destinations - © Xchange.org 2019

The respondents were asked to imagine where they would go if they were given the option and the opportunity to go to any country in the world, except for Myanmar. One in three Rohingya (33%) would consider Saudi Arabia as a potential destination. The three most popular locations after Saudi Arabia were Canada (21%), the USA (21%), and Australia (16%), while a considerable proportion of the sample, 12%, did not want to think about going anywhere else other than Bangladesh or Myanmar.

30-year-old Rohingya male

20-year-old Rohingya male

44-year-old Rohingya male

25-year-old Rohingya male

27-year-old Rohingya male

Potential destinations (about the majority) - © Xchange.org 2019

Moreover, 37% believed that the majority of Rohingya would choose to go to Saudi Arabia if given the opportunity, 22% said the majority would choose Canada, and 21% the USA. Turkey was also among the most popular destinations with 16% of Rohingya adults believing that the majority would choose to relocate to Turkey.

24-year-old Rohingya male

22-year-old Rohingya male

How would you reach that potential destination? - © Xchange.org 2019

Respondents were given the option to freely mention up to three entities that would help them reach their goal of arriving to the desired country they mentioned in the previous question. The vast majority supported they would need help from governments; 30% mentioned the Government of Bangladesh, 4% the government of their respective desired destination countries, 19% the help of both the Government of Bangladesh and the destination’s, and 2% any government’s help. 30% would need help from the United Nations and the UNHCR.

28-year-old Rohingya male

25-year-old Rohingya male

30-year-old Rohingya female

Overall, 31% of Rohingya considered leaving for another country other than Myanmar or Bangladesh, with some specifying that they were considering it irrespective of whether they would get help from governments or humanitarian agencies. Nine respondents specified they would reach their destination by boat irrespective of whether they receive the support of the United Nations or any government. 6% were determined to reach their destination by accepting anyone’s help, including that of a smuggler’s.

Camp 5

Nevertheless, eight in ten (80%) stated they were either scared or very scared to leave for another country, with two in three of those feeling very scared.

No male respondent interviewed knew personally any Rohingya who had left Bangladesh for another country in the last six months. 17 female respondents (or 2.4%) knew at least one Rohingya who moved to Malaysia (12 respondents), India (four), UAE, or Oman (one each).

Feelings about the future - © Xchange.org 2019

A majority of Rohingya adults (49%) were either positive or very positive for the future, with relatively more females optimistic about the future than males; 57% of male respondents leaned towards feeling negative compared to 32% of female respondents.

26-year-old Rohingya female

30-year-old Rohingya male

Camp 10

Conclusion

In March 2019, Xchange returned to Bangladesh to collect first-hand data from Rohingya refugees about daily life in the camps and the movement from a humanitarian crisis to protracted displacement. The three-week long survey conducted by Rohingya enumerators explored topics including Rohingya refugees’ future plans of whether to remain or attempt to escape the overcrowded camps, their trust in officials and NGOs operating within the camps, as well as the shift in violence and illegal activities within the camps. The sample comprised of 1,277 Rohingya adults residing in Kutupalong, Balukhali, Hakimpara, Jamtoli, and Shamlapur refugee settlements.

Almost half (47%) of the interviewed Rohingya did not feel at home at all in the camp in Bangladesh, with 69% stating that nothing had changed in the camps in the last six months. The lack of education for all and employment opportunities were found to play an important role. Six in ten Rohingya were unsatisfied with the quality of education provided for Rohingya, universally highlighting an unmet need for higher education and education for adults.

20-year-old Rohingya male

Moreover, they were generally either unsatisfied or very unsatisfied with both the amount of job opportunities available to them (80%) and the income their families made (92%).

On the other hand, 97% of Rohingya felt either satisfied or very satisfied with the overall help they had been receiving from NGOs operating in their area. 97% supported that they have access to healthcare facilities (e.g. aid stations, hospitals, health centres) but only two in ten were satisfied with the quality of healthcare they had been receiving. Also, 86% identified a need for psychological support.

35% believed that the level of existing violence in the camps had not changed over time. 30% had seen overall improvement in the last six months, mainly due to the increased security in the camps; 47% of respondents believed that violence in the camps had either decreased or decreased a lot. However, those Rohingya living closer to the Cox’s Bazar-Teknaf highway were more likely to have heard talk of violent groups operating in the area, than respondents in other areas. Also, more than one in four Rohingya believed that sexual harassment takes place in the camps and mostly in the streets.

Additionally, respondents showed a high level of awareness around child trafficking; almost all Rohingya parents of children under 18 were afraid to leave their children unattended at night; 91% believed that there were Rohingya families in the camps whose child had been abducted by traffickers since they had moved to the refugee camp.

With regards to social hierarchy in the camps, a majority (46%) considered their block’s majhi as the most important person; 28% the Camp-in-Charge officials and; 24% the head majhi. As a result, the majority of respondents identified that they first ask for help from the block’s majhi when needed, despite one in three having little or no trust at all to them. In contrast, the Rohingya almost unanimously fully trusted the religious leaders (imams), and 82% had a lot of trust in the police, military, and guards of the camps.

98% of respondents often felt stressed or overwhelmed by their living situation. 89% preferred talking about their everyday problems instead of keeping them to themselves, and 95% preferred to ask for the help of others than to solve their problems alone. 97% of Rohingya felt they had enough good friends in the camp and an equal proportion believed that Rohingya and Bangladeshis ‘can be good friends’; 53% had Bangladeshi friends.

Smoking cigarettes and chewing betel nuts were the two most common coping strategies for Rohingya adults. 20% of respondents, mostly males, were cigarette smokers and smoked an average of 9 cigarettes a day. 22% of current smokers had not been smoking in Myanmar prior to moving to Bangladesh. 58% of Rohingya chewed betel nuts; on average eight betel nuts a day.

Regarding relocation, 98.4% would refuse to go to Bhasan Char, the island where the Bangladeshi Government plans to relocate a number of Rohingya in the coming months.

35-year-old Rohingya male

31% of Rohingya would consider leaving for another country other than Myanmar or Bangladesh, with 80% stating they were either scared or very scared to do so. On the other hand, given the option to choose freely, 33% would consider relocating to Saudi Arabia, 21% to Canada, 21% to the USA, and 16% to Australia. However, the vast majority believed they will still be in the refugee camps in the next six months.

93% of respondents, relatively more males than females, said they would return to Myanmar one day. However, 69% did not believe that Myanmar will recognize and accept them as Burmese citizens in the next two years, leading to 73% thinking that repatriation to Myanmar will not happen within this period of time.

31-year-old Rohingya female

28-year-old Rohingya male

24-year-old Rohingya male

To conclude, the findings presented in this report provide a valuable insight into the refugee situation in Cox’s Bazar and help to understand how newly-arrived Rohingya refugees are navigating the transition from temporary emergency to protracted displacement. The data is useful in recognising the ongoing and developing challenges that exist in the camps as a result of this shift, as well as in identifying the priorities for meaningful developments in the medium and long term.

Camp 8W

Acknowledgements

Coordination, Research, Analysis, & Report-writing: Ioannis Papasilekas

Research & Report-writing: Maria Fatas Ortega

Report-writing: Kate Hughes

Contact Us

As an information and research initiative, we are eager to work with a wide spectrum of stakeholders to exchange information and knowledge.

We are looking for partners and funding organizations to support us in conducting a new round of surveys. Please, feel free to send us your proposals.

Copyright © Xchange.org 2019