Central Mediterranean Survey

Introduction

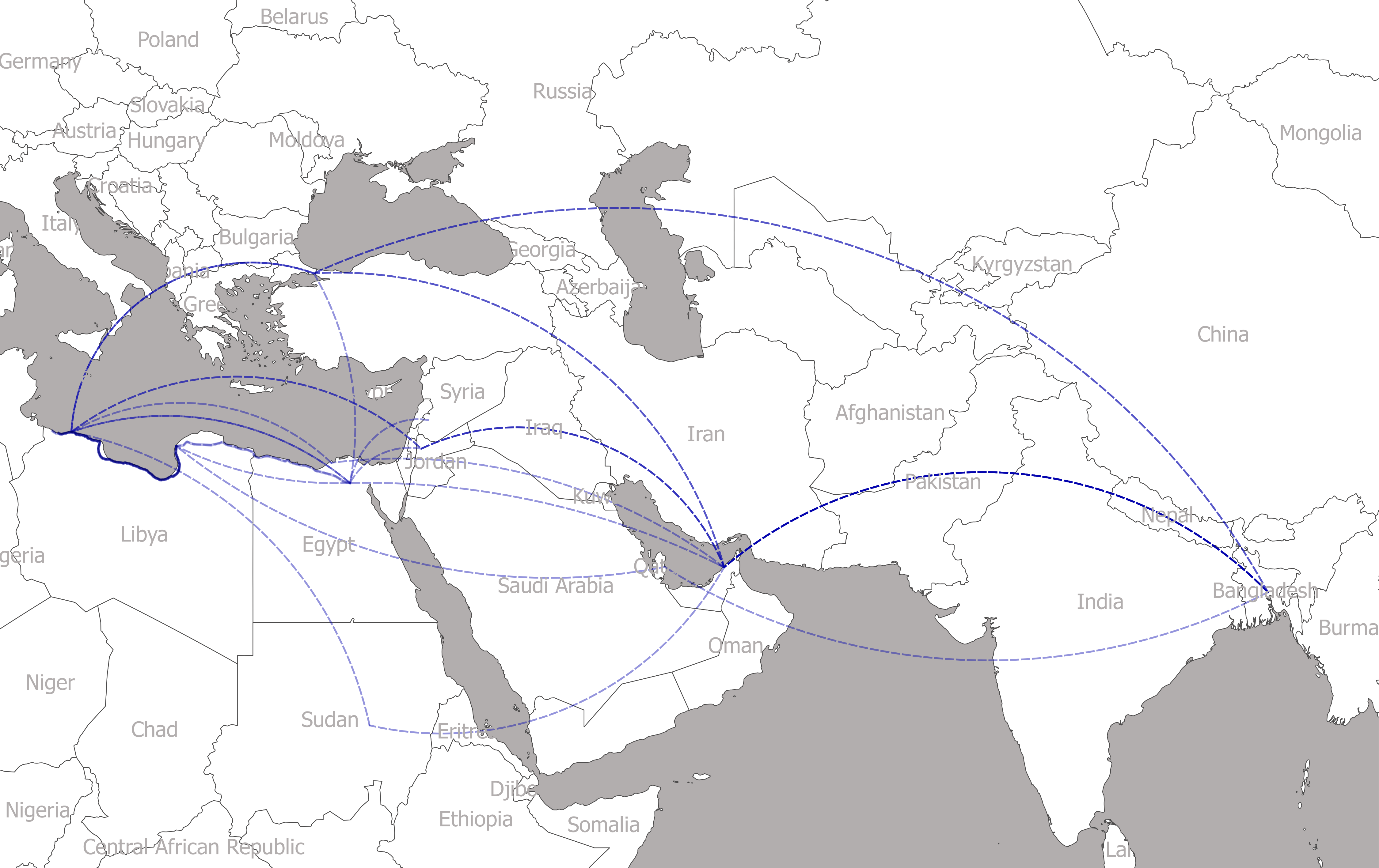

The Mediterranean is home to three primary maritime routes that migrants use to reach Europe: The Eastern Mediterranean Route (EMR), via Turkey and Greece, the Central Mediterranean Route (CMR), from Libya to Italy, and the Western Mediterranean Route (WMR), from Morocco to Spain. The CMR is the most active channel to Europe, and the key route for migrants travelling from Sub-Saharan Africa. Migrants travelling this route hail from varying countries of origin and have wide ranging motivations for taking these dangerous journeys. The routes themselves change constantly based on the dynamics of the smuggling networks in the region, and as a result, these mixed migration flows are complicated to track and map effectively.

Central Mediterranean Sea, migrant boat roaming before being assisted by the SAR team.- ©️ MOAS.eu - 2016

Central Mediterranean Sea, migrant boat roaming before being assisted by the SAR team.- ©️ MOAS.eu - 2016

Chinara, Nigeria

The Mediterranean region – the CMR in particular– accounts for the most migrant deaths recorded globally. Since 2014, the CMR has accounted for 88% of all migrant deaths on the Mediterranean routes and in 2016 and 2017, 90% of all maritime migrant deaths in the Mediterranean region (4,581 deaths in 2016 and 2,853 in 2017) occurred there. Now, in 2018, despite a 74% decrease in refugee and migrant arrivals to Italy, the rate of deaths has more than doubled: there was one death for every 14 who crossed from Libya to Italy successfully during the first three months of the year. This number excludes the vast numbers of migrants that perish en route to Libya in the desert, whose bodies may not be recovered for weeks, if at all. IOM’s Missing Migrants Project recorded more than 1,700 migrant deaths in 2017, with over 690 reported in the Sahara Desert - numbers are likely to be only a fraction of the reality. Reliable statistics on migrant deaths and disappearances are extremely difficult to find. The importance of solid data on migrant arrivals, deaths, and those missing cannot be underestimated; however, these figures represent much more; each migrant death or disappearance is a missing loved one. It is for this reason that since 2014, search and rescue (SAR) Non-governmental Organisations (NGOs) like Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS) have been collectively responsible for the rescue of over 100,000 lives in the Central Mediterranean and 41% of those rescued at sea in 2017.

In 2016, Xchange established a presence on The Phoenix, the MOAS SAR vessel patrolling the Central Mediterranean Route for migrant boats in distress. Through our exposure to those rescued on board, we uncovered incredible stories of resilience that we could not ignore. In 2017, we returned to the Phoenix to conduct interviews with migrants who wished to share their stories with us.

Through our work, we became increasingly aware of the gaps in public and policy awareness of what hardships are experienced on a migrant’s journey to Europe. One thing is clear: migrants will continue to leave their homes in search of safety and better livelihoods for themselves and their families, despite the risks. With this in mind, this report aspires to shed light on the individual journeys of the migrants we met, with the following dual objectives:

- Conduct a cross-border analysis by collating and mapping the mixed migration trends and routes which led migrants to Libya and to cross the Mediterranean.

- Document and categorise abuses reported by respondents in order to detect patterns and migrant vulnerabilities in different migration hubs.

❝ For this survey, an “incident” is defined as an event or abuse of some kind which was considered serious or meaningful enough by the migrants themselves. ❞

For the purpose of analysis, the data on journeys obtained in this survey were classified into the four following routes according to the description given by respondents:

- The Sudanese Route

- The Nigerian Route

- Mixed West African Routes

- Asian Routes

Likewise, data obtained on ‘incidents’ was categorised into primary and secondary incidents. Primary incidents (experienced/witnessed) included kidnapping/ arbitrary arrest/ detention; human trafficking; slavery; extortion; physical abuse; torture; rape; robbery; fraud; injury by gunfire; killing; death. Secondary incidents included Inhumane or degrading treatment in prisons, compounds or camps; inhumane treatment in transit and/or in travelling vehicles; threats to life and violent attacks; trauma; humiliation; racism; and lack of access to asylum or protection mechanisms.

The data collected for this report therefore captures aspects of the complex and arduous journeys that migrants from diverse backgrounds may endure en route to Europe. This report merely casts a magnifying glass over the complex and dynamic migration patterns that converge in the CMR; it is not representative of the 'migrant story' as a whole - each story is unique. For a broader, more representative picture of the migration context, consistent monitoring and analysis is necessary.

During August-September 2017 we collected over 100 testimonies from migrants on board the MOAS Phoenix. This is what we found.

Context

Human smuggling and trafficking

The respondents to our survey had restricted access to regular legal routes to Europe and therefore lacked the ability to migrate safely and regularly. As a result, respondents sought passage through smuggling networks. The smuggling business that transports migrants to Libya is dynamic as well as ruthless, and as evident in this survey, smugglers have increasingly taken advantage of vulnerable irregular migrants to maximise profits by imposing high prices, restricting freedom of movement, using unsafe transport, selling migrants to third parties to be exploited, and holding migrants for ransom, to maximise profits.

Victoria, Cameroon, incident location Sabratha (Libya)

Across the African continent, where most of our respondents’ journeys took place, human smugglers constantly adapt to, and influence, local and regional politics and economies. However, human smuggling networks form only one link in the chain, amongst formal and informal state actors, criminal gangs, armed groups, and local communities whose local economy has become entwined with these irregular migration routes. Most networks consist of independent, often family owned entities with complex alliances. Although each network operates differently, most appear to have a range of individuals fulfilling various roles within the wider network, including coordinators and organisers, recruiters, transporters, and additional service providers, such as forgers of passports, and other official documentation.

Whilst fluid in nature, smuggling networks have varying degrees of professionalism and complexity in organisation, coordination and modus operandi, depending on the geographical location, opportunities, routes and clientele. For example, across many West African routes, individual smugglers often operate from local hubs, handling one segment of the journey, and then hand migrants over at borders to other smugglers, forming larger loosely organised transnational chains. Within these structures, migrants often pay individual smugglers and intermediates as they go from one hub to the next. These single-service providers do little more than transport migrants to the adjacent hub and often have roots within the local community rather than the migrant communities they serve and little knowledge or connections along the rest of the routes. The single service demand is further facilitated by free mobility within the Economic Community of Western African States (ECOWAS) region, weak border controls and visa-free programmes between several West African and North African nations. As a result there appears to be less demand in more specialist and organised services.

Contrary to this, as migratory flows from the Middle East, the Horn of Africa and Asia have significantly increased over the years, routes from these regions towards Europe have been dominated by highly integrated human smuggling networks, often with offshoots in migrants' countries of origin. The increase in demand, logistical and organisational ability, and financial capital to procure sea, land or air transport, false documentation, and to pay bribes, means that migrant smuggling networks can offer a wide variety of services. This includes “pre-organised stage to stage” smuggling, with minimal stop-overs and payment transactions. Smuggling of migrants may then occur through step by step journeys coordinated by key individuals that are in frequent communication with each other. Sophisticated networks like this frequently bribe and collude with corrupt government officials, local militias, and armed groups, to secure passage or to further exploit migrants.

❝ Whilst migrant smuggling generally involves consent in the sense that a service is requested in exchange for payment, many migrants who begin their journey voluntarily can become victims of human trafficking and other forms of exploitation along the way. Contrary to human smuggling, trafficking is committed for the purpose of exploiting the trafficked person by means of force or other forms of coercion, fraud, deception and abuse of power. Whilst there is a clear legal definition between human smuggling and trafficking the de-facto reality is far more blurred. ❞

Ginikawa, Nigeria, incident location Tripoli (Libya)

Chichima, Nigeria, incident location Sabha and other various locations

Libya

North Africa acts as a regional hub for mixed migratory movements –those fleeing war and conflict, poverty, discrimination, or lack of economic opportunities. Although popular belief is that all migrants intend on travelling onwards to Europe, in fact only 20-35% of migrants on the move across West and East Africa towards North Africa continue to Europe; many travelling the trans-Saharan route claim Libya or Algeria as their final destinations. The majority of irregular trans-Saharan migration is in fact circular, intra-African migration, and often for economic purposes. However, Libya also demonstrates its importance in the migrant story as the final stopping point for those who make the maritime crossing to Europe. All respondents to our survey entered Libya using various smuggling networks. The country was also the location in which respondents experienced the most incidents of human rights abuses.

Libya has been a destination country for migrants and refugees across the African continent since the 1970s. Until the outbreak of civil war in 2011, Libya was perceived as a relatively economically stable country with good links to the Middle East. The breakdown of the state’s governing structures combined with the rise of militarisation in the country marked a crossroad for the human smuggling market; developments and changes happened fast, based on the relationship dynamics of the tribes and militia. Thus, the environmental, socio-economic and political realities fuelling the migratory flows, as well as high levels of political instability in Libya and countries in the region, have resulted in a vibrant multi-million transnational human smuggling industry which plays a central role in the facilitation of irregular migration and its routes.

In post-Gaddafi fragmentation of Libya, the subsequent liberalisation of the human smuggling market and better access to financial infrastructures such as Hawala, provided established Libyan human smugglers, armed groups and militias to internationalise their networks. Additionally, coastal smuggling networks underwent extensive changes. Due to increasing demand, more risks were taken at the expense of the migrants making the crossing, resulting in higher numbers of deaths. This was, in part, due to the declining quality, as well as frequent overloading, of the vessels used for these journeys. The inferior vessels were packed with migrants and sent out to sea with no intention of them reaching European shores. Smugglers would typically give migrants on board a satellite phone, GPS tracker, and occasionally, lifejackets, small rations of food and water, with the instruction to launch a distress call once outside Libyan waters. If there was a response to the signal, it would not necessarily guarantee the migrants on board a passage to Europe.

❝ As of May 2018, there were 184,612 internally displaced (IDPs) Libyans and 52,031 registered refugees and asylum seekers in the country. ❞

Migrants both on the ground in Libya and intercepted at sea by the Libyan authorities are often transferred to national detention centres, where serious human rights abuses have been reported. The lack of a migration framework in Libya has given effective control to state and non-state actors within migrant detention centres. Migrants are vulnerable to arbitrary arrest and placed there regardless of their immigration status. Foreigners residing in Libya who have not legalized their stay within a period of two months after entry are considered “illegal migrants” and subjected to penalties, including “detention with hard labour or by a fine not exceeding 1,000 LYD.” Conditions at detention facilities are often appalling; as demonstrated in the Incident Analysis, migrants may be held for prolonged periods without judicial review, in grossly overcrowded holding cells, all the while subjected to torture, beatings, forced labour, sexual violence, and a lack of food and clean water.

❝ Libya is party to the 1969 Organisation of African Union Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa. In addition to this, the Libyan interim constitutional declaration of 2011 gives right to claim asylum in the country. However, UNHCR is currently responsible for registering asylum seekers and determining refugee status as the country has not yet enacted national legislation in this regard, nor are there the necessary structures for a functioning asylum system. ❞

Methodology

Sampling and Data Collection

In 2017, Xchange conducted a cross-sectional survey to obtain first-hand data from migrants aboard the MOAS SAR vessel, The Phoenix, in the Central Mediterranean Sea. The face-to-face interviews were conducted by a Senior Researcher on four different SAR missions from May to July 2017 using a purposive (non-probability) sampling technique. Only migrants travelling through the most transited routes and who had arrived into Libya no more than four years prior to the interview were chosen. This survey sought to identify:

- Current migratory routes across Africa, Asia, and the Middle East and;

- Incidents experienced by migrants on the move.

Moreover, there was no specification applied with regards to the interviewees' immigration status; the term "migrant" is used throughout the whole report to refer to anyone (e.g. refugee, asylum seeker) intending to reach Europe through crossing the Mediterranean. The Senior Researcher aimed to include a diverse group of participants to capture a broad picture of the migratory routes and a variety of potentially experienced or witnessed events or incidents, reaching a sample size of 117 migrants.

The questionnaire included questions regarding the migrants' demographic profiles, push or pull factors, types of journeys and routes, time and cost of travel, countries and locations crossed, most significant incidents witnessed since departing from their home countries, as well as their future aspirations. More specifically:

- Migratory routes: 1. Personal data including age, nationality, sex; 2. Record of the route used from home country (including all transit hubs), journey time frame, cost, type of transport etc.

- Human rights violations: 1. Personal data including age, nationality, sex of victim; 2. Perpetrator of the violation; 3. Date of violation; 4. Location of violation; 5. Geo-location of incidents (coordinates); 6. Description of violation in the form of an audio testimony and post-transcript.

- The primary incidents considered in this report are: Kidnapping, Arbitrary Arrest/Detention, Human Trafficking, Slavery, Extortion, Physical Abuse, Torture, Rape, Robbery, Fraud, Injury by Gunfire, Killing, Death.

The use of a mobile survey application allowed the data to be collected offline and uploaded to the server after each mission at sea. During the interview the respondent was provided with a detailed map of Africa to identify the transit hubs and thus allow the researchers to subsequently reconstruct the respondent’s routes. The raw data was cleaned and analysed eight months later.

All interviews were conducted with informed consent, in a separated and comfortable area (on the bridge of the vessel) to ensure privacy and preserve the dignity of the respondents. The principle of confidentiality was also explained to all respondents before the interview. Within this report, every participant was provided with a pseudonym reflective of their country of origin and gender to protect their identity.

Limitations

Data collection was intended to span over six separate missions onboard The Phoenix SAR vessel. However, due to the premature termination of the MOAS missions, data collection was terminated after the fourth mission. It was therefore not possible to interview all the intended nationalities in the original project design, as certain nationalities are known to cross the Mediterranean Sea later in the year (e.g. Eritreans) and were not present during the missions Xchange were on board. As a result, far fewer interviews were collected than intended: the sample size was restricted to 59% of the target (200). In addition to this, and to ensure high quality data and analysis for the report, some respondents’ data were not used as the data collected was not sufficient to reconstruct their full routes.

Since migrants were taken onboard 25 miles off the Libyan coast, the interviewer often had less than one day to conduct the surveys until disembarkation in Italy. Hence, we had limited resources (i.e. one male enumerator and no female enumerator).

The conditions onboard the vessel were difficult, as it was usually overloaded with typically more than 400 migrants during each SAR operation. During the time the interviews took place, mobility and access to the areas where migrants were allocated were restricted.

To facilitate interviews, interpreters were used. However, this increased the length of the interviews and might have also influenced the level of detail and accuracy of the testimonies. Moreover, 16% of the incidents were recorded with no information on country of origin of the respondent thus limiting the precision of findings.

Furthermore, for practical reasons, the interviewer asked for the major incidents - not all incidents. Incidents such as extortion, which typically occurs in multiple stages of the route, were not systematically collected, allowing the migrants to primarily focus on those events they thought were most important/relevant. Hence, even though extortion is mentioned throughout the report, its frequency of occurrence is most likely higher than presented.

With regards to data quality, several factors may have prevented an interviewee from openly sharing their feelings. Some respondents may not have wished to disclose serious and traumatic incidents experienced during their journey, particularly those of sexual nature. Therefore, the figures for sexual abuses are likely to be greater than reported here due to the stigma and culture of shame around the subject and the social costs of disclosure.

Overall, the findings presented in this report should be interpreted with caution and as outcomes of a mere snapshot, not as a broadly representative picture of all migrant movements in the Central Mediterranean Sea.

Migrant Profiles

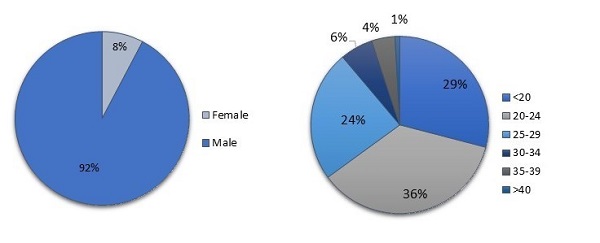

Gender and Age of respondents

Gender (left) and Age (right) of respondents - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

Overall, the survey sample consisted of 117 people of various nationalities; 108 men and nine women. Only 12 respondents were not from the African continent. The reasons for fewer female respondents may include, but are not limited to, the fact that fewer women usually make such journeys and the limited female enumerators available to the Senior Researcher.

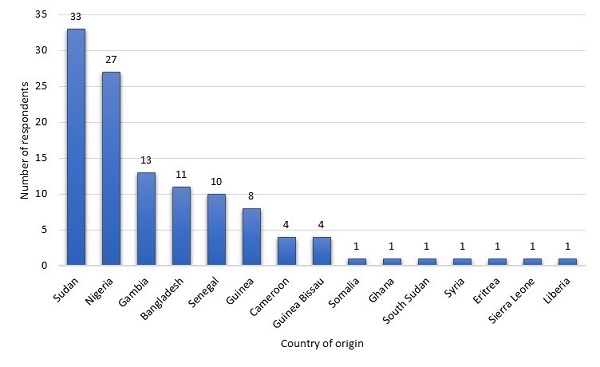

National origin of respondents

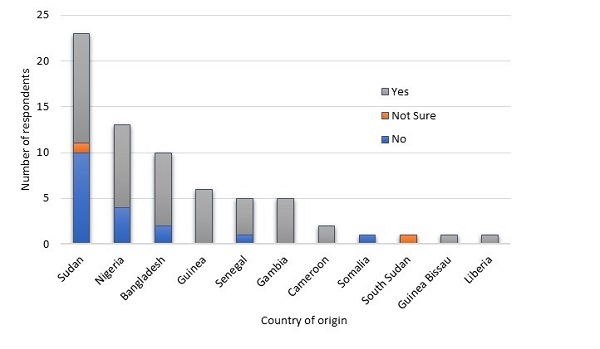

Number of respondents by country of origin - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

The majority (51% of the total of respondents) came from Sudan and Nigeria (60 respondents), whereas the 40% came from other various African countries. Bangladeshis were also highly represented in the sample (9.4%).

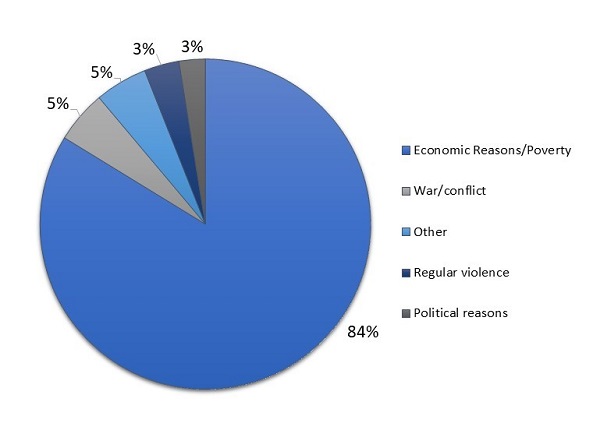

Why did you leave your home country?

Reasons why respondents left their home country

(Regular violence refers to any type of violence that causes

insecurity in non-conflict situations.) - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

Although a few respondents (5%) had unique reasons for leaving their country (e.g. seeking a better education system or wanting to become a professional football player), most respondents (84%) were pushed to leave due to poverty and economic instability to improve their own and their families’ wellbeing.

The majority of the respondents were asked if this was their first attempt at crossing the CMR. Interestingly, for 12% of the sample it was not their first attempt. However, this was the first attempt for all respondents from Sudan, Guinea Bissau, Cameroon, Somalia, South Sudan, and Liberia. There were eight respondents in total who tried to cross twice, one Senegalese who tried to cross for the third time and one Senegalese and one Gambian for whom it was the fourth documented attempt. However, it is not uncommon for migrants to have attempted the crossing more than four times. Three in four respondents (74%) were travelling by themselves, whereas the rest had at least one person accompanying them, i.e. a family member or a friend.

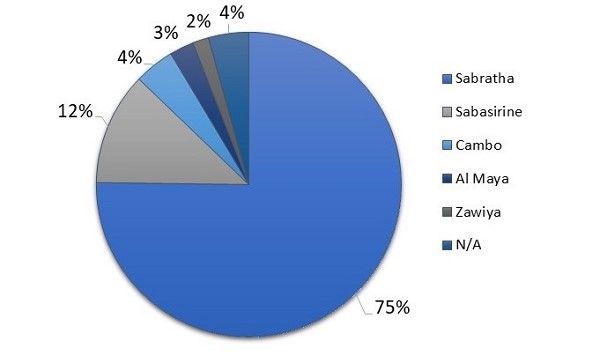

Place of departure

Place in Libya where respondents departed from- ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

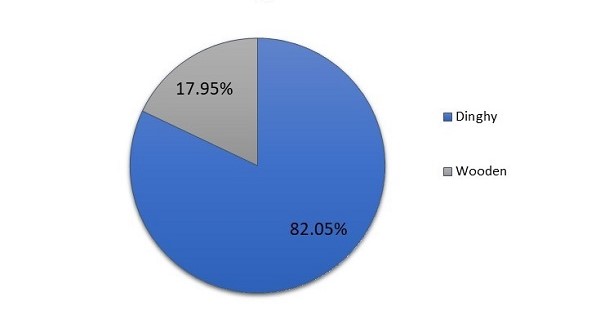

Type of boat

Proportion of respondents using each type of boat to cross the Central Mediterranean Route - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

The majority of respondents departed from Sabratha, at the coast of Libya. They were smuggled using either a wooden boat (18%) or a dinghy (82%). The dominant usage of rubber dinghies illustrates the changing smuggling dynamics in Libya due to increased demand, whereby cheaper vessels are bought and imported from abroad.

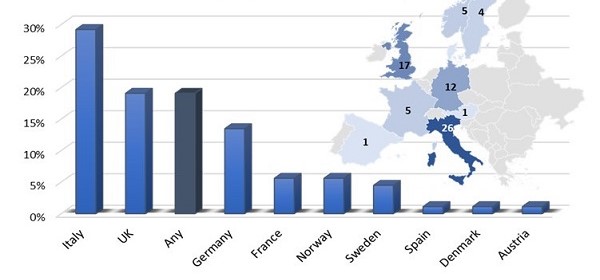

Ideal Destinations in Europe

Ideal destinations in Europe (% of respondents mentioning a preference) - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

With regards to their short-term aspirations, 89 respondents were asked in which country of Europe they would like to live after their journey is over. 29% stated Italy as their preferred destination. One in five (19%) wanted to go to the UK and one in five (19%) did not show a preference.

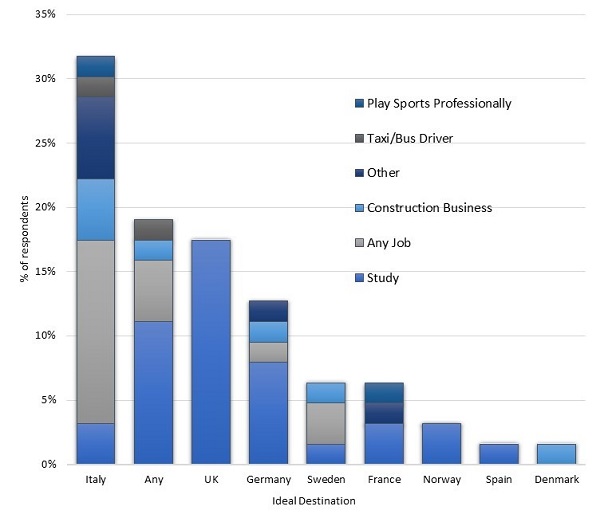

Expectations in Europe by ideal destination

Expectations in Europe by ideal destination - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

Migrants were also asked what their aspirations were once in Europe. 63 of 89 migrants (70%) had specific plans. The remaining 26 (30%) did not provide any information. Almost half reported that they wanted to study (e.g. English, Law, Medicine, Agriculture) to improve their employment chances and support their families back home. Notably, everyone wishing to go to the UK, Norway, and Spain intended to study. One in four migrants did not have a specific job in mind at the time of the survey.

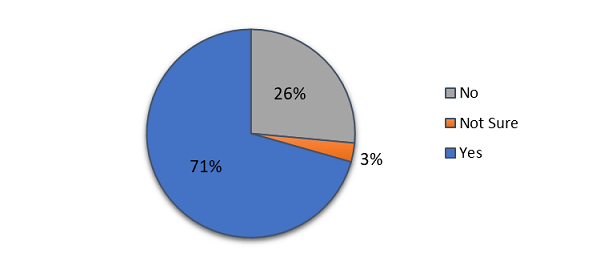

Are you intending to return to your home country?

Migrants' intentions to return to their home country - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

Intentions to return by country of origin - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

60% of the sample were asked whether they had the intention to return to their home country in the future. 48 (71%) intended to return, 18 (26%) did not, and two (3%) were undecided. Split by gender, eight of the nine female respondents and seven in ten (68%) male respondents had the intention to return. This indicates that, unlike popular belief, many migrants wished to improve their lives and contribute to their family’s wellbeing with increased education and economic opportunities abroad, with most intending to returning.

One in three (34%) reported having family living abroad. However, there was no relationship identified as to whether having family abroad affected the respondents’ decisions to return. Both those who have family abroad (76%) and those who do not (68%) intended to return to their country of origin.

Routes Analysis

One of the survey’s primary objectives was to track the routes that individual respondents took before embarking at the Libyan coast to Italy. While the project's scope was to cover multiple African routes towards Libya, limitations in terms of access to migrants during the mission on board a vessel —and as detailed in the Limitations —meant that we could not cover all the target nationalities anticipated. Therefore, the routes are not representative, but rather a snapshot of the migrants we sampled.

During the survey, each respondent reported a detailed and chronologically ordered list of hubs they had transited during their journey. It comes as no surprise that the most transited hub before entering Libya, was Agadez (Niger). Agadez is a major hub for West and Central African migrants on the move towards Libya, and often onwards to Europe. From our survey, a substantial 61 of 117 (52%) migrants, from five different countries of departure, transited the Nigerien city during their journeys. See below a map representing the number of times a given migration hub was reported to be transited by the respondents (click on the symbols to display the hub name).

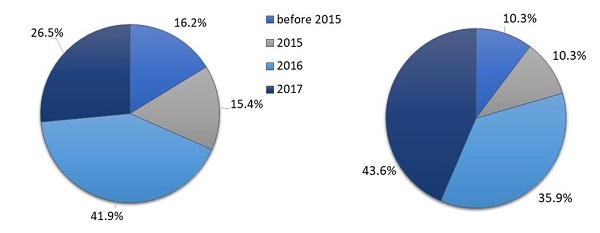

Overall time spent on the road until rescue

(% of respondents) Year of departure from home country (left) -

Year of crossing the Libyan border (right) - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

Most respondents (42%) left their home country during 2016. However, not all migrants crossed the border into Libya during the same year they left their home country. The median time spent travelling to reach Libya was one full month (31 days). However, 20% of the sample (23 individuals) reported spending at least one year on the road until they reached the Libyan border. This reflects the varied types of journeys and smuggling networks used; many migrants' journeys are multi-stage, where they may spend periods of time working to earn money for the next part of their journey; others may not have intended to go north to Libya and onto Europe at all but were left with no choice due to conflict, or a lack of economic opportunities.

This is also reflected in the time that migrants spent within Libya before being rescued at sea, which ranged from 11 days to four years and three months. The median time was 9 months and 26 days. The average time was one year and 15 days. As also demonstrated in the Incidents Analysis, many migrants spent prolonged periods in Libya. Some respondents intended Libya as their final destination country, usually for economic purposes; others spent long periods there to earn money only for the next stage of their journey. Other respondents were trapped in forced labour or interned in detention centres or prisons.

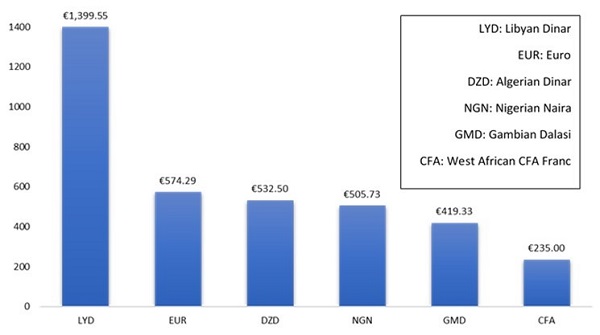

Journey Costs

Average price per journey by currency(in EUR) - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

The cost of a journey to Libya and onto Europe cannot be generalised as it depends on a multitude of factors, including the status of the individual migrant concerned, country of origin, route taken, smugglers employed and their network dynamics, as well as the political climate of the countries they transit. When respondents were asked in what currency they paid for their trip to Europe, 71% reported paying in Libyan Dinars. This indicates that many respondents were likely to be self-funded until they reached Libya, where they then paid for the maritime journey to smugglers. Five per cent paid in Euros, while one tenth of respondents stated that they were too afraid to report anything related to money for fear of reprisals from smugglers. One person worked in exchange for the next leg of the journey. A few West Africans paid for their whole trip in advance in their own currency. Those who paid in Libyan Dinars spent more than double the amount that others paid. This could be due to the type of smuggling method used; those who paid in currencies other than Libyan Dinars did so in advance (two respondents mentioned bank transfers from Guinea or Gambia).

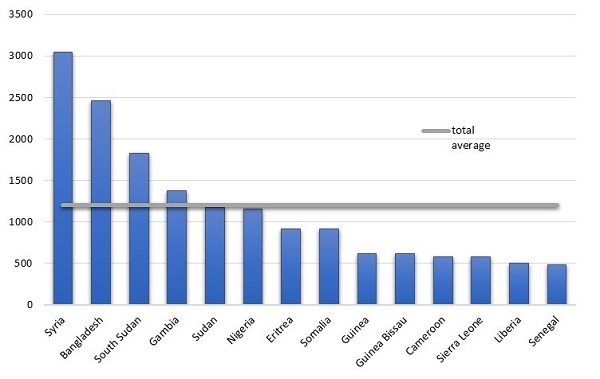

Average price of journey by country of origin

Average price of journey by respondents' country of origin (in EUR) - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

The average cost of the trip stood at 1206 EUR per person. The median cost was 914 EUR. By nationality, we can see that respondents from Syria and Bangladesh paid more. This is unsurprising, as reports indicates that Syrians, known to have larger savings due to economic prosperity before the Syrian war, often pay for superior, smoother, and safer passage to Europe, with prime places for their families reserved on less densely packed boats. Bangladeshis, travelling by plane, pay higher prices to be taken from Dhaka to Dubai or Istanbul, and onto Libya, often via “agencies” with the promise of work - a scenario which has also been regularly reported in Gulf countries.

The Sudanese Route

Map showing the Sudanese route patterns towards Libya - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

Calculate Distance

18 of the 33 Sudanese respondents (54%) — mostly from Darfur — transited Chad before entering Libya. 11 entered Libya directly via the so called Motallat (“triangle” in Arabic), a desert region where the Sudanese, Libyan, and Egyptian borders meet.

Tina, a town located a few kilometres from the Sudanese-Chadian border was the main crossing point into Chad with 90% of those interviewed transiting this border hub. Many of those travelling the Chadian route reported having passed through or worked in Kouri Bougoudi Gold Mine, located in the Aouzou strip, a piece of land long at the centre of territorial conflict between Chad and Libya, before crossing the Libyan border towards Qatrun.

Those who entered Libya directly from Sudan transited the Sudanese capital Khartoum and Dongola city in the north, before heading west towards Kufrah, the largest district in Libya. The median length of time for a migrant on this route to reach Libya was 21 days.

The Nigerian Route

Map showing the Nigerian and Cameroonian route patterns towards Libya - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

Calculate Distance

25 of 27 Nigerian respondents were from the southern states of Edo, Imo, Delta, Rivers, Anambra, and Lagos. Southern States, Edo State in particular, have in recent years become known for trafficking young girls and women into the sex trafficking industry in Italy. Only one respondent was from the north (Bauchi State) and another one from central Nigeria (Abuja). Beside the Nigerians, four respondents from Cameroon reported having crossed into Nigeria before joining this route.

The Nigerian route shows regularity in terms of transited hubs: Kano, a north-western Nigerian city close to the Niger border with regular bus services to Niger, was transited by all respondents before entering Niger. Once the Nigerian-Nigerien border was crossed, all respondents headed north to Zinder in Niger before arriving at the last urban centre before the most popular migration hub in Africa, Agadez. Most respondents crossed the Ténéré Desert, in the south-central Sahara towards the Libyan border, and then reported having transited Qatrun and Sabha, oasis cities in southwestern Libya (78%). Following the route north towards the Libyan coast, some respondents mentioned having transited Ash-Shwayrif and Bani Walid en route to the country’s capital, Tripoli.

Mixed West African Routes

Map showing the western African route patterns towards Libya - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

Calculate Distance

Median total length by land: 6,031 km

Guineans:

Average length by land: 6,294 km Median length by land: 5,940 km

Senegalese: Average length by land: 6,268 km

Median length by land: 6,011 km

Gambians: Average length by land: 5,697 km

Median length by land: 6,017 km

Bissau-Guineans: Average length by land: 6,174 km

Median length by land: 6,071 km

The Mixed West African route included respondents travelling from diverse West African countries of origin, including Gambia, Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ghana and Guinea. Patterns emerge from the data on these routes, but they are not concrete nor generalisable. In total, 38 respondents transited through the Mixed West African Route to reach Libya.

35 respondents from various West African countries of origin passed through Mali via the capital, Bamako. Of these, 27 respondents transited Burkina Faso (Bobo-Dioulasso and Ouagadougou), as well as Niger (Niamey and Agadez) before entering Libya. After crossing the Libyan border, respondents typically headed north east towards Qatrun before reaching the coastal cities of Tripoli and Sabratha. However, four of the 27 respondents did not enter Libya from the south, and instead transited through Algeria before entering Libya from Debdeb.

The remaining eight (of 35) respondents went straight from Mali to Algeria (without transiting Burkina Faso or Niger) via the Niger River course, towards Gao and then north to Kidal region. before crossing the border into Algeria.

One respondent (of the 38) travelled through Burkina Faso and Niger to Libya without crossing through Mali; one respondent flew to Casablanca (Morocco) and then continued through Algeria; one respondent travelled through Mauritania to Morocco and onto Algeria.

Typically, those migrants who crossed Algeria passed through Timiaouine in the country's southwest once they crossed the border and then moved north-east towards the mountainous oasis city of Tamanrasset before reaching Debdeb, and then Gadamis, an oasis Berber town, on the Algerian-Tunisian-Libyan border. Six of the West African respondents reported having worked in Northern Algerian cities to finance the last part of the journey to the Libyan coast and the Sea crossing.

Abdoulaye, Guinea, incident location Kidal (Mali)

Asian Routes

Map showing the Asian route patterns towards Libya - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

Calculate Distance

In total, there were 12 individuals interviewed from the Asian continent and one from the Middle East: one respondent from Syria and 12 from Bangladesh. In recent years, the number of South Asian migrants arriving in Italy along the CMR have increased. All respondents (11) to our survey from South Asia were of Bangladeshi origin. Bangladeshi respondents typically travelled in two, three, or four stage journeys from Dhaka (Bangladesh) to Libya via different airports. The respondents’ first stops were, in order of frequency: Dubai (UAE) (seven respondents), Istanbul (Turkey) (two respondents), Amman (Jordan) or Doha (Qatar) (one respondent in each). From there, three respondents flew to Libya, whereas the remaining eight flew to Cairo (two individuals), Amman (two individuals), Istanbul (two individuals), Alexandria, or Sudan (unspecified airport); from Istanbul one individual made an extra stop in Cairo before entering Libya.

Salim, Bangladesh, incident location Tripoli (Libya)

Eight of the 11 Bangladeshi respondents entered Libya via Tripoli Airport; two respondents landed in Benghazi; whereas there was one who did not specify at which airport in Libya he landed. From Dhaka to Libya, their journeys lasted from one to four days.

It is worth noting that almost all Bangladeshi respondents (10) entered Libya at least one year before the interview took place, indicating that these respondents worked in Libya prior to departure. This was the first maritime journey for all respondents except for one, for whom this was the second attempt.

All Bangladeshi respondents wished to go to Italy; two mentioned that they did not intend on returning to their home country. All but one Bangladeshi respondent was not travelling alone.

The single Syrian respondent left his country in 2013, flying from Damascus to Egypt, and then by car to Libya, a journey which lasted two weeks.

Incidents Analysis

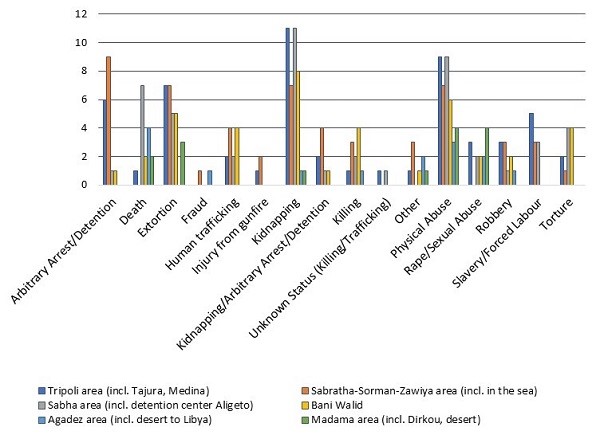

The survey data comprised of 114 testimonies, including 362 primary incidents. This analysis attempts to dissect the available information in these testimonies to aid the reader to form a picture of the often-dangerous incidents respondents experienced in transit. It is important to note, however, that these incidents do not occur in isolation; they happen simultaneously and throughout the entire journey, as the map below shows.

Each incident is considered separately and uniquely so as not to undermine its weight and severity. Most respondents (69%) recorded more than one incident in their testimony. All respondents interviewed had either suffered themselves (73%) or witnessed (27%) a variety of all the primary incidents at some point during their journey.

Most frequently, respondents experienced detention and extortion; they were likely to suffer physical abuse if they were men, and rape if they were women; many were robbed or pressured into forced labour; often, respondents were held for ransom, or even witnessed killings and deaths of other migrants. During their journeys, respondents also faced harsh travelling conditions and inhumane living conditions; any suffered medical complications from dehydration, exhaustion, lack of food, and poor hygiene.

❝ The primary incidents considered in this research are: Kidnapping, Arbitrary Arrest/Detention, Human Trafficking, Slavery, Extortion, Physical Abuse, Torture, Rape, Robbery, Fraud, Injury by Gunfire, Killing, Death. ❞

The four incidents experienced or witnessed most frequently across all routes were:

- Arbitrary Arrest/Detention;

- Extrotion;

- Kidnapping;

- Physical Abuse.

These seem to have been experienced or witnessed to a larger extent by migrants travelling the Sudanese Route and the Mixed West African Route. However, there was a general feeling of chaos and lawlessness on all the routes taken by respondents. Incidents took place, not only at check-points, prisons, and compounds, but also at markets, streets, camps, places of employment, and in transport vehicles. This means that, irrespective of which route was taken, or the duration of the journey, respondents faced a continuum of violence and exploitation from beginning to end, at the hands of smugglers, government officials, gangs, insurgent groups, and abusive citizens.

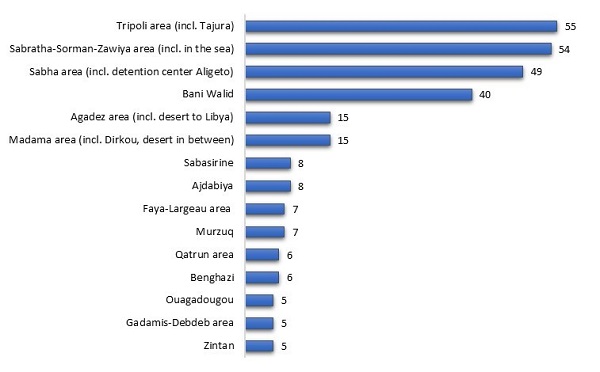

The most dangerous country location for our respondents, was Libya and its borders (271 incidents). This is unsurprising, considering that all routes, including those from Asia, converged in Libya, and more specifically, towards the same hubs leading to the Libyan coast. Additionally, as detailed in the Context, Libya’s breakdown in governance and border control since the revolution has created a hotbed for migrant smuggling and abuse. Respondents may take months or even years from when they first leave home to board a boat at the Libyan coast, most spending long periods of time in Libya, leaving them more vulnerable to abuse. “Hotspots” for abuses were located primarily in pre-departure coastal cities Sabratha and Zawiya, and the capital, Tripoli, where respondents were often held before being transported to the coast. Bani Walid and Sabha were common to three routes out of four.

Following this, Niger was the second most dangerous (32 incidents), then Algeria (16 incidents), Chad (12 incidents), Mali (11 incidents), Burkina Faso (10 incidents), Sudan (eight incidents), and Egypt (two incidents).

Incident Locations

Number of incidents by location (top 15 mentioned locations) - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

Number and type of incidents by most mentioned locations - ©️ Xchange.org, May 2018

As evident in the graph, of all incidents, kidnapping occurred most frequently to respondents. This incident occurred primarily in Tripoli and Sabha, Libya. During these incidents, respondents were held for periods of time, for money, or trafficked to other gangs. Bangladeshi respondents explained that they were attacked, kidnapped or extorted while they were working in Libya. Most of these incidents took place in Tripoli or Benghazi.

Mohammed, Bangladesh, incident location Tripoli (Libya)

Similarly, respondents described extortion as well as physical abuse frequently across all routes and locations. However, both occurred most frequently in Tripoli, Sabratha-Surman-Zawiya, and Sabha. Extortion and physical abuse occurred at the hands of government officials, gangs, Libyan civilians, and smugglers. However, often, respondents could not tell who they were abused by, as many stated that perpetrators were imitating officials by “dressing up as” police officers.

Munir, Sudan, incident location Tubruk (Libya)

High numbers of arbitrary arrest/detention (and uncertain cases of kidnapping/arbitrary arrest/detention) occurred at the coastal towns of Sabratha-Surman-Zawiya, as well as Tripoli, indicating that respondents may have been detained at their final stops during their land journey due to heavier border or police presence, or after being intercepted during the maritime segment of their journey. Up to August last year, around 8,000 of the estimated 400,000 migrants in Libya were detained in approximately 30 official detention centres in Libya, with many more in unofficial ones. This may shed light on why there were more reports of deaths witnessed in these locations; detained migrants are more likely to suffer from medical complications, severe long-lasting psychological issues or chronic illnesses or even disabilities caused by malnutrition, a lack of hygienic WASH facilities, or unattended wounds from torture.

Idrissa, Guinea Bissau, incident location Surman (Libya)

As a result of incarceration, a number of other incidents often took place. For example, respondent’s testimonies show evidence of slave trade emanating from prisons:

Sawalo, Gambia, incident location Tripoli (Libya)

Bilal, Sudan, incident location Murzuq (Libya)

Slavery and racial discrimination in Libya have become an unprosecuted norm. Migrants are extremely vulnerable to abuse, particularly in Libya where racism is ubiquitous; male respondents were sometimes made to work on construction sites or farms while females were drawn into the sex trade. Evidence surfacing from recent investigations shows active slave markets and slave auctions in Libya, including in Zuwara, Sabratha, Gadamis, Zintan – locations featured on routes taken by migrants who took the survey.

Abdul Kareem, Sudan, incident location Ajdabiya (Libya)

Tebu and Tuareg tribes in the south-west of Libya, most of whom had been employed by the military during Gaddafi’s reign and who subsequently ended up unemployed, also joined the slave trade. Respondents mentioned “Tuareg rebels” who kidnapped, attacked and/or extorted money from them.

Daouda, Guinea, incident location Agadez (Niger)

Five incidents, with no specific trend of place, recorded cases of racism shown by Libyan Arabs towards African migrants. Certain cases specifically indicate that they were refused healthcare and/or medical attention while travelling, or were asked for high amounts of money in return which they could not afford:

Moses, Liberia, incident location Bordj (Algeria)

Others were beaten and/or experienced violence due to their race:

Kelechi, Nigeria, incident location Sabha (Libya)

Many migrants within Libya face multiple barriers to any form of public healthcare due to discrimination as well as a lack of means of transportation, or distance from public medical facilities. Resultant health issues or disability from untreated medical issues only increases their vulnerabilities. Additionally, travelling long distances to access medical facilities increases migrants’ vulnerabilities to kidnapping and robbery.

Torture had been experienced frequently by respondents. Most cases of torture were recorded in two specific locations: Bani Walid and Sabha, with two cases at the Sabha Detention Centre. This demonstrates the total lack of protection and human rights for migrants in Libyan detention centres. Torture also occurred at the hands of kidnappers. Often, respondents were forced to phone/video-call their families while the torture took place, with the perpetrators demanding a ransom. Methods of torture recorded by respondents included beatings with electrical cables, wooden sticks, iron pipes, hammers or other tools, smashing fingers/nails, sexual abuse, burning, denial of food and medical treatment, and humiliation.

Aziz, Sudan, incident location Bani Walid (Libya)

It is worth noting that some accounts refer to minors being used as kidnappers and torturers.

Abu Hanifa, Sudan, incident location Bani Walid (Libya)

Cases of rape or sexual violence were recorded in all locations apart from Sabratha. Often, rape and sexual violence occurred at detention centres and check points or crossings. This demonstrates total abuse of power of authorities and smugglers, where sexual abuse is used as a form of extortion; migrant women are at their mercy, so that they can proceed with their journeys. Unwanted pregnancies and long term physical and mental health issues often result from such abuses.

Tayo, Nigeria, incident location Madama (Niger)

Hassana, Nigeria, incident location Tripoli (Libya)

Chichima, Nigeria, incident location Sabha (Libya) and other various locations

Although unclear due to the fine line between smuggling and human trafficking, the latter was present on all routes. Various testimonies refer to it:

Abdul Kareem, Sudan, incident location Ajdabiya (Libya)

Though evidence of human trafficking was not clearly found in the testimonies of migrants taking the Bangladeshi route the nature of the Bangladeshi journey – travelling via various flights to Libya - indicates potential incidents of trafficking; respondents may have purchased flights via agents with the promise of finding work but were instead kidnapped and forced to pay more money for entry to Europe irregularly.

The desert

Desert journeys require special consideration, as most respondents’ journeys included long periods transiting the harsh and dangerous desert environments in which many incidents (61) occurred. A significant number of these incidents were committed by rebels, smugglers, and the Libyan military. Respondents described incidents where smugglers abandoned them in the desert when they saw military or police approaching, effectively leaving them to die. Rebel or militia groups sometimes captured or attacked travelling convoys of migrants, even shooting and wounding/killing migrants.

Jamal, Ghana, incident location Niger-Libya Checkpoint (Duruku)

29 respondents (17% of the total number of narrated incidents) recorded incidents happening in the Sahara Desert, one in three (31%) in Niger, one in four (26%) in Libya, one in five (20%) in Chad, and the remaining incidents in Sudan, Algeria, and Mali.

The desert also naturally poses more dangers of dying from harsh environmental conditions, including dehydration, starvation, and exhaustion. This is demonstrated by the fact that the most witnessed incident in the desert was death (11 incidents, almost half (48%) of the total number of incidents of witnessed death). The most experienced incidents in the desert were arbitrary arrest/detention (eight incidents) and physical abuse (eight incidents). Many testimonies also mentioned being attacked and/or kidnapped by Tuareg rebels in the desert who sometimes handed them over to Libyan rebels. These once nomadic tribes seem to have become part of a smuggling chain which delivers hundreds of migrants through dangerous desert terrain to the more central and busy hubs in the north.

Conclusion

In 2017 Xchange set out on the MOAS SAR vessel, the Phoenix, with the intention of shedding light on the individual journeys of the migrants we met, with the following dual objectives:

- Conduct a cross-border analysis by collating and mapping the mixed migration trends and routes which led migrants to Libya and to cross the Mediterranean.

- Document and categorise abuses reported by respondents to detect patterns and migrant vulnerabilities in different migration hubs.

The study employed a qualitative research approach; a Senior Researcher interviewed rescued migrants in four separate SAR missions with the use of a semi-structured questionnaire. All our respondents had restricted access to regular legal routes to Europe and therefore lacked the ability to migrate safely and regularly, instead using dangerous smuggling networks. Overall, the survey sample consisted of 117 people of various nationalities (108 men and nine women), most of whom came from the African continent. The most represented countries of origin were Sudan, Nigeria, and Gambia; Bangladeshis, however, were also highly represented in the sample. Most respondents (84%) were pushed to leave due to poverty and economic instability, seeking to improve their own and their families’ lives.

The liberalisation of the human smuggling market in Libya has allowed established Libyan human smugglers, armed groups and militias to internationalise their networks, drawing in migrants from across the African continent and beyond. As our data demonstrates, the most dangerous country location was Libya and its borders. Many respondents spent long periods of time within Libya, from 11 days to four years and three months. “Hotspots” for abuse were located primarily in pre-departure coastal cities Sabratha and Zawiya, as well as the capital, Tripoli. Niger (Agadez), as the most transited hub before entering Libya, was the second most dangerous location. Following this, the majority of incidents outside Libya and Niger were recorded in hubs in Algeria, Chad, Mali, Burkina Faso, Sudan, and Egypt.

As the data demonstrates, regardless of which route was taken, or the duration of the journey, respondents faced a continuum of violence and exploitation at the hands of smugglers, government officials, gangs, insurgent groups, and citizens. Our respondents to the survey experienced a multitude of human rights abuses, including detention and extortion, physical abuse, rape, robbery, and forced labour; they were kidnapped and held for ransom, and many were tortured to extort money from their families; they constantly witnessed the dehumanisation and deaths of other migrants, and they were frequently detained in intolerable and inhumane conditions in prisons and detention centres. On their journeys, they faced harsh travelling environments in the desert which for many resulted in medical complications from dehydration, exhaustion, lack of food, and poor hygiene.

Interviewees frequently spoke of other migrants on their journey who were taken away and “never came back”. These migrants might have managed to escape, or they may have been trafficked, lost in the desert, or left for dead. The possibilities are many and highlight the fact that many migrants continue to be unaccounted for and much more research is needed to fill the information gaps on this part of migrants’ journeys.

The present report is not representative of the “migrant story” as a whole but rather an insight into the perilous journeys of migrants on the move. However, keeping the migrant “voice” at the centre of the data is of paramount importance in all such studies. Retrospective, in-depth studies of the migrants' experiences could uncover many more events of abuse and possibly become the basis for raising awareness and solving part of the problem, including identifying more smuggling networks, finding the perpetrators, and even predicting future movements and incidents. Interviewing those with secure immigration status in Europe is an important step which could provide researchers with richer qualitative data on their experiences and could prove to be a valuable source of information.

Equally, longitudinal studies following the migrants' journeys since their departure from Libya and documenting their everyday lives and/or struggles in Europe could provide a better understanding and holistic picture of who these people are, what they have been through, what their aspirations were and whether they have changed over time, and their level of integration and acculturation in the host countries. Longitudinal data could inform all national, European, and international policy-making and be the basis for better future strategies on improving both the migrants' and the local populations' lives.

Key Concepts and Definitions

Asylum seeker

Project funded by moas.eu

Contact Us

As an information and research initiative, we are eager to work with a wide spectrum of stakeholders to exchange information and knowledge.

We are looking for partners and funding organizations to support us in conducting a new round of surveys. Please, feel free to send us your proposals.

Copyright © Xchange.org 2017