The end of ‘emergency rule’ and limited returns by displaced Rohingyas are positive developments in Myanmar’s restive Rakhine State – but the core issues remain unaddressed

A woman and two young children walk on the outskirts of Say Tha Mar Gyi IDP camp, near Sittwe, Myanmar, on May 26, 2015 (Alex Bookbinder).

Myanmar’s outgoing president, U Thein Sein, had a mandate to oversee Myanmar’s transition to democracy when he took office in 2011. On March 30, his term officially ended, giving way for U Htin Kyaw, representing the National League for Democracy (NLD) and its leader, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

As his last action in office, U Thein Sein repealed a state of emergency imposed in 2012 in Rakhine State, following violence that mostly targeted Rohingya Muslims. Waves of violence in June and October of that year left some 140,000 Rohingyas and other Muslim minorities displaced across the state, and affected smaller numbers of ethnic Rakhine Buddhists.

An announcement in state media on Tuesday justified the order, claiming that the Rakhine State government had found “no threats to the lives and property of the people.”

The state of emergency was used as justification for a litany of abuses against both Rakhines and Rohingyas, said Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director at Human Rights Watch. While the end of emergency rule is welcome, the rationale for ending it at this particular juncture is suspect.

“There hasn’t been a clear reason expressed [for lifting the state of emergency], except that [Rakhine State] is no longer insecure. I don’t think anybody believes that,” he said.

Among other factors, Robertson says, getting rid of the state of emergency just before the new government takes office “could be a booby prize for Aung San Suu Kyi to make sure she has to deal with the situation in Rakhine first steps out of the gate.”

Street scene in Ohn Daw Gyi IDP camp, near Sittwe, Myanmar, May 26 2015 (Alex Bookbinder)

Rakhine State remains a tinderbox. The two communities – Buddhist and Muslim – remain effectively segregated by the state government. The severe restrictions placed on Rohingyas’ freedom of movement and their lack of citizenship status have not been addressed. Rescinding the state of emergency is unlikely to change this.

Compounding matters, a new armed group, the Arakan Army – which claims to represent the interests of the state’s ethnic Rakhine majority – launched a renascent insurgency in parts of the state in mid-2015, although its primary target is the military, not Muslims.

Although Myanmar’s government has long had fraught relations with all of the country’s ethnic minorities, the Rohingyas – who number approximately 1.2 million inside Myanmar – are singled out for an unparalleled level of exclusion. The vast majority are denied citizenship under Myanmar’s stringent 1982 citizenship law, and they are officially classified as “Bengalis,” implying they are illegal immigrants from neighbouring Bangladesh, despite the fact that practically all can trace their ancestry in the country back many generations.

Security forces maintain a large, permanent presence in northern Rakhine State, enforcing rules that prevent Rohingyas from moving from township to township without receiving prior permission – restrictions that, critics say, amount to indefinite detention, and which have had a severe impact on Rohingyas’ ability to earn a living.

The Rakhine State government has starkly limited Rohingyas’ access to healthcare, education, and adequate nutrition, and has erected barriers for international NGOs seeking to alleviate their problems.

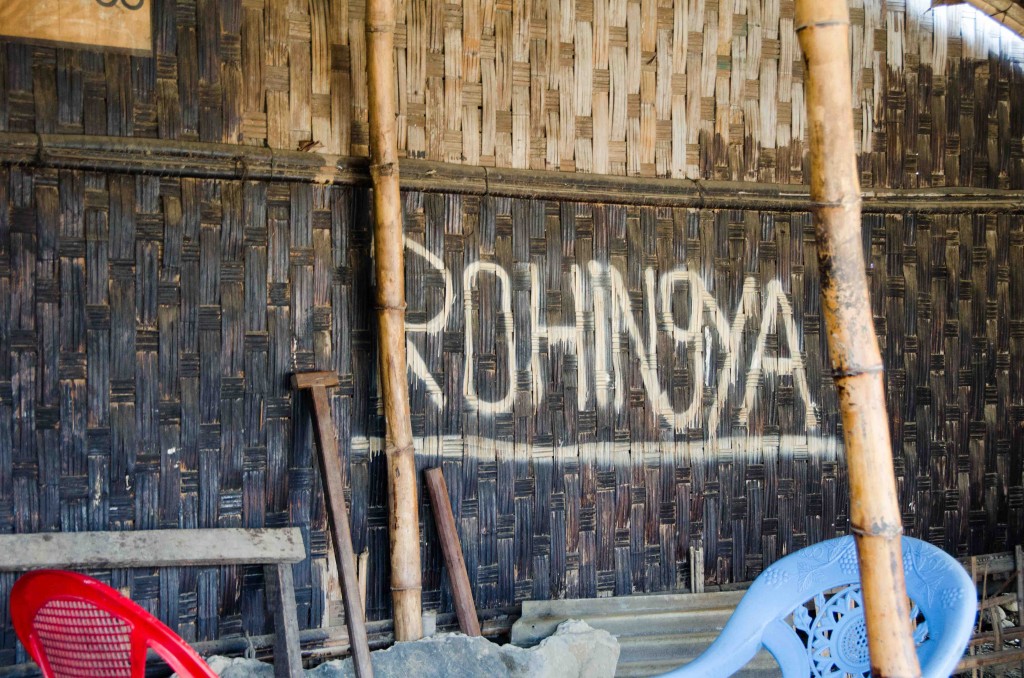

Graffiti in a teashop in Say Tha Mar Gyi IDP camp, near Sittwe, Myanmar, on May 25, 2015 (Alex Bookbinder).

These restrictions – and routine abuses and violence perpetrated by the security forces – have prompted hundreds of thousands to flee by sea over the past decade, with most seeking safe haven in Muslim-majority Malaysia.

In 2014 and the first quarter of 2015, an estimated 88,000 people left Rakhine and southern Bangladesh by boat, according to UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, making perilous crossings facilitated by predatory human traffickers.

While a crackdown on trafficking networks and horror stories filtering home have largely put a stop to these risky sea voyages, the unpredictability of Rakhine State’s ethnically charged political landscape means that a mass exodus of Muslims could occur at a moment’s notice.

“If things [were to go] badly, and there were another outburst of violence, with the Rakhine angry at the fact that they didn’t get the chief ministership position, there could be real movement out,” Robertson said. “Everything there is very, very tense.”

Happy returns?

On 21 March, UNHCR announced to the press that some 25,000 displaced Rohingyas had been returned to their places of origin, with a small number resettled elsewhere, as part of a process started by the Rakhine State government last March.

The returnees were given cash handouts to rebuild their homes by the Rakhine State government, in Kyauktaw, Minbya, Mrauk-U, Pauktaw and Rathedaung townships.

But while this is ostensibly a positive development, the returnees in these townships were mostly displaced to areas relatively close to where they came from originally. Most of the 140,000 Muslims displaced by the 2012 violence were forced out of Sittwe, the Rakhine State capital, and around 100,000 remain confined to an archipelago of camps outside of the city.

A Rohingya fisherman tends to his boat on Ohn Daw Gyi beach, a major jumping-off point for refugees seeking security and livelihoods in Malaysia, on May 26, 2015 (Alex Bookbinder).

Continued tensions with the ethnic Rakhine majority will make it extremely difficult for these individuals to resettle within the boundaries of the city proper, raising fears that the IDP camps that ring the city will become permanent, segregated settlements.

Budget constraints faced by UN agencies and international NGOs have prompted a gradual reduction in the amount of assistance Rohingya IDPs are eligible for, despite the fact that conditions on the ground have not improved markedly. But these recent returnees will still be eligible for international assistance, Kasita Rochanakorn, a spokesperson for the UNHCR in Yangon, told Migrant Report, despite the fact that they are no longer considered ‘displaced.’

And so long as punitive restrictions on freedom of movement are not eased, these vulnerable populations will remain reliant on aid indefinitely. “Lifting restrictions on freedom of movement is very, very important at this point, as a core international human right,” said Robertson of Human Rights Watch.

“The question is, now, does [the government] follow through and ensure that, by lifting the state of emergency, they address all the various restrictions that have been imposed on the Rohingya, particularly the restrictions on freedom of movement, which is crippling Rohingyas’ ability to earn a living?”

*CORRECTION: Rochanakorn is a spokesperson for UNHCR, not UNDP.