The Gambian Boy who Lost his Family but Found his Voice in Italy

April 2015 was the deadliest month on record for migrants crossing from Libya to Europe with an estimated 1,250 people perishing in just two accidents off Libya. NANCY PORSIA spoke to one of the survivors from that dark month in the Mediterranean’s history who gave her a heartwarming story of hope.

Alì in Gambia when he was a child.

The last time Alì Sohana saw his mother was in the northern Nigerien outpost town of Agadez; a major regional hub for sub-Saharan migrants making their way to Libya, many in the hope of crossing to Europe. It was early 2015 and Alì was just 17-years-old.

He was headed for Europe with his widowed 45-year-old mother, Aisha, and his older brother Mohammed, or Paps, as Alì calls him. But the group didn’t have enough money for all of them to make the next part of the journey so Aisha convinced her boys to proceed without her. “She told us it was our time to seek a better future in Europe as we were young,” Alì recalls, as he strolls along the narrow streets of the southern Italian city of Matera where he has now settled down.

The cobbled walkways of the ancient city could not be more distant or different from Tallinding, the sprawling Gambian village he left from. The family had run into tough times early on. Alì’s father and older brother died separately when he was just three, leaving his mother to raise two children all on her own.

The context of the country did not help either. Despite being an attractive and fertile tourist destination, the narrow West African state has struggled endlessly under the ruthless rule of President Yahya Jammah, who was defeated in December 2016, after a 22-year iron-fist stint.

Alì’s home town Tallinding .

Almost half of the population lives on less than $2 a day, and while this represents an improvement over the years, the gross national income actually decreased since Jammah took power in a coup in 1994. Put simply, while the economy has been generally growing in the past decades, most of the proceeds did not really go to ordinary Gambians.

The mismanagement and corruption was sustained over time through fear and intimidation where opposing voices were crushed through arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance and torture.

It is no surprise, therefore, that this small nation of just 2million people finds itself in the list of the top ten populations of irregular migrants to have entered Europe in 2016, ahead of Pakistan, and the much larger, and much more populous neighbour, Senegal. Similarly, the Gambia finds itself among the top ten when it comes to the contribution of remittances (20%) to the GDP. Throughout 2016 alone, almost 13,000 people left Gambia for Europe through the so-called “Back Way”.

Ironically, unlike many of his co-nationals, Alì was not driven to seek the promise of Europe. His family more or less decided for him, out of necessity. His odyssey, however, ended up being among the most tortuous.

It was April 12, 2015, when the old wooden fishing boat carrying him and his brother started sinking some 80miles off the Libyan coast with 500 people on board. They were within sight of rescuers but had not quite made it yet when the mayhem began. “When we saw the European ship, everyone stood up abruptly. The driver (a young Senegalese man who had been trusted with the helm) yelled at everyone to get down or he would leave the boat’s wheel. Nobody would listen and after a while he did and the boat began to crack” Alì recalled.

He still grimaces as he recalls the moment he saw people tipping helplessly into the water. The ones who couldn’t swim were thrashing in a frenzy while others went down almost immediately. Those in the hold, like Alì’s brother, did not even have a moment’s notice.

Against the odds, the brothers had managed to get this far but were destined to be separated forever at this last leg of the journey. Months before they had been separated again, in the Libyan desert.

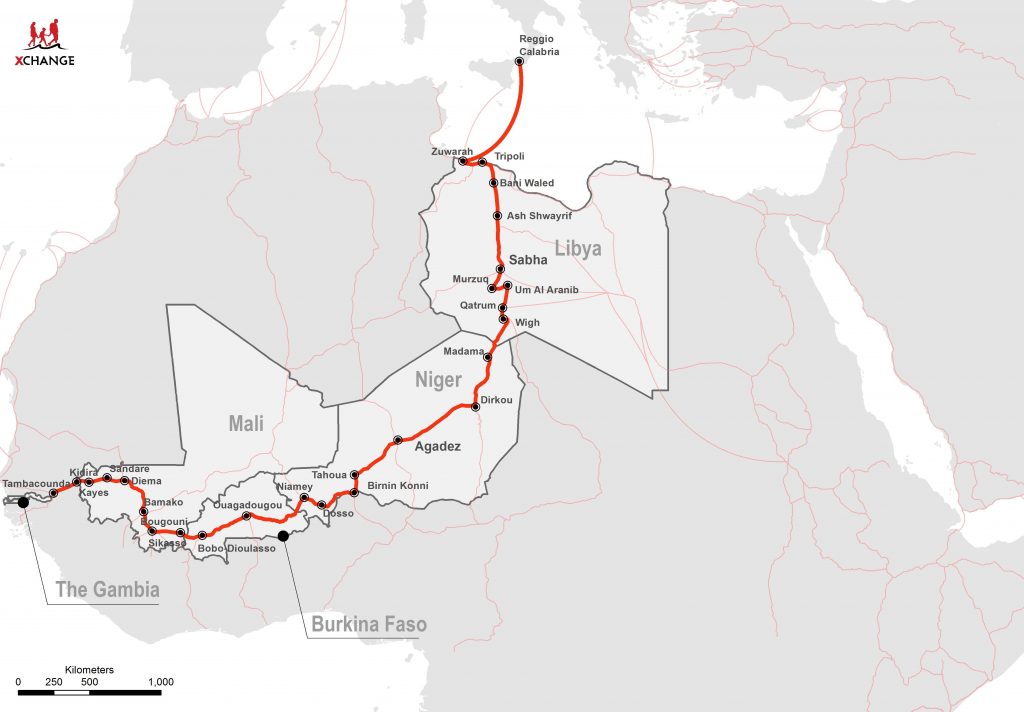

A typical smugglng route from The Gambia to Libya.

“We left Agadez, squeezed on a pick-up truck. After a day of driving, the Nigerien smuggler pointed to a black dot on the horizon, saying that was the border village”. At that point they stopped and walked for two days across the desert, sleeping rough and having to improvise.

“At night we lit a fire with plastic jerry cans, but it only lasted a few minutes. We all used to fight for a few seconds next to the fire.” After crossing the border, the plan was for them to head for Sabha, the capital of Libya’s southwest region of the Fezzan; and the main regional transit hub for migrants moving onwards to Tripoli. But as soon as they neared the outpost town of Qatrun, the group Alì was with got ambushed by armed men.

Paps managed to escape with some others but Alì wasn’t so lucky. “These men, wearing a uniform, took us to a prison where we were asked our nationality. The day after we were transferred to an abandoned farm where guards had no uniforms and beat us all the time forcing us to call home and ask our families for ransom”.

Luckily, Alì got an early break and after just four days of captivity the group he was with organised a breakout and he joined them. They managed to make it out and the group stuck together all the way to Tripoli. They moved at night and rested during the day, traversing unknown desert territory. Two people would be sent ahead to explore the next town until they got to Sabha, 200kms north of Qatrun. There they found a Nigerian mediator who gave them directions to catch a bus to the capital; a journey of some 800kms.

After two days of driving, Alì ended up in Gurji Street, an avenue west of Tripoli where hundreds of migrants find shelter inside the unfinished buildings that line the thoroughfare. His brother was also in Gurgi. In no time, Alì met someone who knew his brother and took him to him.

The sun was shining again on the two brothers. This time, Paps wanted to make sure they wouldn’t get separated again. He placed him on the third floor of an unfinished building block and demanded that he stay there while he went out to work. “My brother told me not to move. He used to come every day to bring me food. I was alone and had only a blanket”.

After two months spent in the shade of the concrete shell he called home on Gurji Street, Paps returned with great news; he had made enough money for the sea crossing and they would be heading out immediately. The following day, they left for Zuwara, a coastal town 120kms west of Tripoli, once the main embarkation point for migrants till 2015. Paps had everything worked out, they dressed as women and took a “taxi” with another migrant.

“Along the route we were stopped several times at checkpoints. An armed man pointed his torch in my face. I was so scared that if you put an egg on my belly, it would be fried in a minute” he said, laughing as he recalled the comical scene. At the gates of Zuwara, armed men took them aboad a pick up and drove the into a farm in Abu Kamash, a town at the far end of Libyan territory, 30 km West of Tunisian border.

Inside the farm, south of the town centre, 600 people, including many women and children, were held by Libyan smugglers for a week, beaten daily up and left with no food or water. “They said that we had to lose weight to board. They were brutal. The Libyans used to enter our room searching for women and pick them away. When the women returned after a few hours, they used to cry without saying a word,” Ali recalled, looking down as he went over the painful memory. It’s clear he feels some sort of guilt for not being able to intervene but he was an adolescent at the time and like all the other people in that situation, completely powerless at the mercy of the armed smugglers.

The departure came out of the blue. The smugglers barged into the farm carrying AK-47s and they started herding everyone outside. During the transfer, Paps told Alì he felt like he was not going to make it to Italy as he felt too weak. “I shouted at him that he would have to take care of me,” Alì recalled. Suddenly bullets hit the ground between the two brothers’ feet and before they knew it they were separated again.

The migrants were split into small groups and taken out on rubber boats before being transferred to a wooden vessel offshore. Paps was with one of the groups that ended up in the hold, while Alì was on the deck. The last time Alì saw his brother was when he resurfaced briefly, likely unconscious or dead, amid a sea of bodies, some floating lifelessly and others desperately trying to stay afloat.

“Everybody tried to grasp on anything on their way down. It was chaos. Then I saw my brother resurfacing. I stared at his body for few seconds and then he slipped away.”

From that moment on, Alì was completely on his own, an unaccompanied minor about to enter a new and unfamiliar country he didn’t ask to be in. His only possession was a pink bracelet; the only thing the smugglers did not take from him before he boarded the boat.

At first he was taken to a reception centre in the city of Reggio Calabria, before being transferred to a similar facility in Naples. In those early days his only concern was how to tell his mother about Paps’ death. When he found the opportunity and the courage to call her, his mother’s first reaction was disbelief. “She didn’t even believe that it was me on the other end of the line. I had to sing on phone our intimate lullaby to gain her trust”.

She never really accepted the loss and over the next months he hardly heard from her. And then, just one year after losing his brother, Alì received news that his mother had passed away. He still doesn’t know the exact circumstances of her death but he strongly suspects she may have taken her life.

Alì found himself in a dark place again but in the meantime he had also started slowly planting roots in Matera. The theatre company Centro Arti Integrate (IAC – Integrated Arts Center) had enrolled Alì into a programme they ran with a local association of volunteer doctors for migrants, called Tolbà, inside the reception centre for unaccompanied minors he stayed at in the nearby town of Salandra.

SALANDRA: February 2016, theatrical workshop at centre for migrant minors in Salandra.

“On stage, I realised I could have a voice. The theatre and all people I met on the stage saved me ” Alì says of his newfound passion for theatre in fluent Italian. Since his early steps on stage, Tolbà hired him as a cultural mediator thanks to his ability to speak Italian, English and five more Western African dialects. The IAC also contracted him as a theatre collaborator for his acting skills.

Alì has now moved into his own apartment and settled in Matera. When he entered the apartment for the first time the big double bed with a thick mattress in his bedroom took him back to memories of his mother: “I wished my mother was here to sleep with me on that bed… she had never had a bed with a mattress”.

But the biggest gift Matera gave Alì was that of a new family. “I thought I was alone as all my family’s members died. I didn’t think I still had a future, but here I found a new family” Alì says struggling to hold his tears back. They are the people who gave him this new chance, Grazia and Chicco, from Tolbà and Nadia and Andrea, founders of the IAC.

The 36-year-old art director, Andrea, in particular has a special place in Alì’s heart having taken the role of his mentor earlier on. “Few weeks ago I was on a bus heading to Rome for a culture mediation course and I phoned Andrea to chat a bit. I called him papà, speaking Italian, and all people around me just turned their head looking at me with a clear expression of surprise. In that moment I realised that I also have a real family looking after me all the time”.

Two years after Alì left Gambia, President Jammeh is no longer in charge. Huge hope is pegged on Adama Barrow, the man who defeated him at the historic polls. Alì is still to be convinced that Barrow will stick to his pre-electoral promises in the long run but for the time being he is excited at the prospect of traveling back to Gambia with his new family of friends from Matera.

Alì on stage at the Teatro delle Albe in Ravena