“I’m a Rohingya and I want to show the world that I’m a Rohingya.”

36-year-old Rohingya woman

Introduction

More than 700,000 Rohingya Muslims have fled across the border from Myanmar to Bangladesh since 25 August 2017, making the ongoing Rohingya refugee crisis the fastest-growing refugee crisis in the world. However, the Rohingyas have long faced persecution by the state and have been forcibly expelled in waves dating back to the 1970s, engendering a reputation as one of “the most persecuted minorities in the world.” Stripped of Myanmar citizenship under a 1982 law, neither Myanmar nor Bangladesh recognises them as citizens, despite the fact that they consider themselves to be ‘indigenous’ peoples of Myanmar. The most recent mass migration of Rohingya from Myanmar to Bangladesh followed a Myanmar military “crackdown” in response to Rohingya insurgent attacks on security posts on August 25 last year, which the government claims killed nine police officers. The August incidents followed an earlier wave of attacks by Rohingya militants, in October 2016; the Myanmar military’s vicious response sent more than 70,000 over the border in search of safety by February 2017 . Following the August 2017 attacks, ten times that number were forced to flee Myanmar, the result of a campaign of state-led violence that has led to the near-eradication of the Rohingya population within Myanmar itself.

In late 2017, Xchange established a presence on the ground in Cox’s Bazar district of southern Bangladesh, at the epicentre of the refugee settlement area. Through our extensive research, we uncovered hundreds of stories of killings and other mass atrocities that had been carried out in Rakhine State by the Myanmar military and groups of extremist civilians from the majority Rakhine ethnic group.[1] We have collected data and closely monitored developments on the ground ever since.

Soon after the expulsions of Rohingyas from Rakhine State began last year, the Bangladeshi and Myanmar governments agreed to begin a two-year process to return over 770,000 individuals, predominantly Rohingya Muslims, that had fled Rakhine State since October 2016. The first 1,200 returnees were set to do so on 23 January 2018.[5] In anticipation of the first Rohingya repatriations, the Myanmar government has constructed two reception centres and a temporary camp close to the border in Rakhine.[6] On 22 January 2018, however, Dhaka delayed the repatriation, amid a torrent of criticism that such returns were deeply premature, as refugees continued to trickle across the border seeking safety in Bangladesh.[7]

In April 2018, a memorandum of understanding (MOU) signed by UNHCR and the government of Bangladesh established a framework of cooperation between the UNHCR and Bangladesh for the “safe, voluntary, and dignified returns of refugees in line with international standards”.[8] A tripartite deal between Bangladesh, Myanmar, and the UNHCR is still in progress, making the future of the Rohingya refugees living in Bangladesh uncertain.[9]

The prospect of returning to Myanmar has been a central theme running throughout our research. Data collected in the Rohingya Survey we conducted in 2017 showed that 78% of respondents would return to Myanmar if the security, welfare and/or political situation improved, 16% would not under any circumstances, and 6% would return unconditionally.

However, many respondents shared their concerns regarding repatriation. In our most recent Snapshot Survey, conducted in January and February of 2018, a small number of respondents stated unequivocally that they would not return to Myanmar because of the traumas they had experienced there.[10]

“I am very happy after arriving in Bangladesh. When I remember the incidents that occurred, I never want to go back to Myanmar.”

20-year-old Rohingya man

Most importantly, this recent repatriation deal failed to consult the Rohingya. It failed to outline what conditions they may face upon their return or include guarantees for the provision of basic rights, including citizenship, freedom of religion, freedom of movement, and right to employment, among other factors, which would leave the Rohingyas’ situation upon return no different in practice from the persecution they had just fled.[11] Taking matters into their own hands to voice opposition, a number of Rohingya refugees from Balukhali camp presented a letter to the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Myanmar, Ms. Yanghee Lee, listing their demands before being repatriated to Myanmar. Seven of these conditions were listed as non-negotiable pre-requisites before they would even consider repatriation in any form.[12]

In this survey, Xchange seeks to understand a critical component of this tragedy that has largely been overlooked: what the Rohingya understand about the proposed repatriation processes, and what they desire and fear as individuals and as a community. This report builds upon Xchange’s three previous Rohingya Surveys conducted in early 2016, September-October 2017, and January-February 2018; it considers the views of more than 1,700 Rohingya refugees who arrived after 25 August 2017, across 12 refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, and who potentially face repatriation (or refoulement) to Myanmar.

During April-May 2018 we collected over 1,700 testimonies from Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar (Bangladesh) – This is what we found.

Inside Unchiprang refugee camp – © MOAS.eu/Dale Gillett 2018

Context

Rohingya Muslims are the largest Muslim community in Myanmar and form a distinct ethnic group, with their own language and culture.[13] Rohingya Muslims -and other Muslim ethnic groups- are subject to severe discrimination from the government as well as marginalization from the general population. The Rohingya are considered “illegal immigrants” from neighbouring Bangladesh despite considering themselves indigenous people and being able to trace their roots back centuries into the territory which now forms Myanmar. As a result, the Rohingya have faced decades of protracted displacement, discrimination, limited access to education and employment, as well as restrictions on marriage, birth registration, health services and freedom of movement. These restrictions have increased significantly in recent years, particularly after attacks on their homes and properties in 2012 that resulted in the displacement of hundreds of thousands internally and the ‘hardening’ of an extant Apartheid system across the northern part of Rakhine State.[14]

The majority of Rohingya Muslims live in the northern areas of Rakhine State in north-western Myanmar, concentrated in Maungdaw, Buthidaung, and Rathedaung townships. Rakhine State is one of the most deprived states in Myanmar, and suffers from chronic poverty, poor infrastructure, limited access to basic services, few livelihood opportunities, compounded (and created) by decades of government neglect..[15] Though both Muslims and Buddhist communities in the state have been subjected to government oppression post-independence, as a predominantly Buddhist country, Rakhine’s Muslim populations have been singled out for particular abuse, with prevailing discourse deeming most of them ‘illegal immigrants’ undeserving of basic rights or dignity.[16]

The Bangladesh Government has historically provided shelter and humanitarian relief to Rohingyas that have fled Myanmar, with considerable assistance from international humanitarian organisations. The majority of Rohingya refugees reside in Cox’s Bazar district, a popular Bangladeshi tourist destination, which is now known simultaneously for being home to ‘the longest natural beach in the world’ and one of the most protracted refugee crises of our time.[17] It is also one of Bangladesh’s poorest districts, suffering from chronic food insecurity and malnutrition at moderate levels, as well as poverty levels above the national average.[18]

Prior to the recent influx of more than 700,000 Rohingya refugees, Bangladesh hosted more than 200,000 documented Rohingya Muslims from Myanmar. This population arrived in Bangladesh as the result of multiple ‘crackdowns’ on the Rohingya by the Myanmar military, the most significant of which occurred in 1978 and 1991-1992.[19]

In 1978, army brutality in Rakhine State as part of “Operation Nagamin,” ostensibly designed to weed out illegal immigrants, ultimately forced more than 200,000 Rohingya out of the country to Bangladesh.[20] The Bangladeshi government, quickly overwhelmed by the influx, requested a repatriation agreement with Myanmar. Though Rohingya refugees were initially reluctant to return, more returned as the camp conditions began to decline and food was rationed to the extent that the Rohingya faced starvation.[21] Many individuals and their descendants expelled in 1978 remain resident in Bangladesh to this day. In 1982, the Myanmar government made significant amendments to the country’s citizenship laws, which served to de facto exclude the Rohingya from citizenship and resulted in the creation of the world’s single largest stateless population.

In 1991, after another wave of attacks by the military, approximately 250,000 Rohingyas were forced to flee to Bangladesh.[22] The increasing number of Rohingya refugees led Bangladesh to request international assistance from UNHCR to provide assistance to the refugees.[23] A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) was subsequently drawn up between the Bangladeshi and Myanmar governments which resulted in the repatriation, between 1993 and 1997, of more than 200,000 Rohingyas who could prove their origins in Myanmar. The UNHCR ultimately refused to take part in the process when evidence emerged of Rohingyas being coerced to return against their will, a concept known as refoulement that is against international law. In 1993, the UNHCR once again agreed to facilitate returns after signing an MOU with the Bangladesh Government. [24] However, approximately 30,000 refugees in Bangladesh were unable to give the required evidence of their previous residence in Myanmar. As a result, they were granted refugee status by UNHCR and permitted to stay in Kutupalong and Nayapara camps, two “official” government-run camps in Cox’s Bazar District. [25]

Violence in Rakhine State has been particularly piqued since 2012, with widespread injury and death, the razing of villages, and mass displacement.[29] These clashes are widely believed to have been orchestrated by elements within the security forces and government, as well as ethnic Rakhine Buddhist nationalists.[30] In October and November 2016, Rohingya men, allegedly from the insurgent group, Harakah al-Yaqin, or “The Faith Movement”, attacked three border posts in Maungdaw and Rathedaung townships in Rakhine State, killing nine police officers. The Myanmar military responded with a brutal crackdown in a major operation that resulted in extensive human rights abuses and resulting in the flight of 87,000 Rohingyas to Bangladesh. The most recent government-sanctioned crackdown on the Rohingya, that started on 25 August 2017, was, the government claimed, a “clearance operation” in response to the same group, rebranded as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), that were allegedly behind attacks on 30 police posts and an army base, killing 11 members of the Myanmar security forces.[31]

The Bangladeshi authorities view the recent influx of Rohingyas as a temporary problem, solved by a policy of “quick and safe return” to Myanmar. The government is therefore reluctant to identify the Rohingya as or “refugees”, preferring the nomenclature “forcefully displaced people from Myanmar” (FDMNs). This refusal to acknowledge the vast majority as refugees means that Bangladesh hopes to limit its responsibility for them. As a result, the Rohingya live a harsh existence in the refugee camps across the district, which are little more than open-air prisons.[32] They are unable to participate fully in family life, nor integrate into local Bangladeshi communities, and as our Snapshot Survey indicated, they face cramped living conditions, limited WASH facilities, restricted livelihood and education opportunities, and multiple protection issues.[33]

The new repatriation agreement between the Bangladesh and Myanmar governments contains terms and conditions that mirror the 1990s repatriation deal. The Rohingya must agree to repatriation on “temporary resident” status, and provide proof or previous residence in Rakhine State through providing Myanmar authorities with documentation.[35] This is an impossible burden of proof for most to achieve, as in 2016 and 2017 hundreds of Rohingya villages were razed to the ground, destroying most of the Rohingya residents’ worldly possessions and prompting them to flee, in many cases, with the clothes on their backs.[36] There are also no guarantees that they would be allowed to return to their home villages, many of which have been destroyed in any case: the construction of grim “processing centres” and vast “transit camps” may in fact be the creation of permanent infrastructure to contain them indefinitely if they do, in fact, return.[37] The Myanmar government has a poor record in this regard. More than 120,000 Rohingyas that fled their homes in 2012 remain in supposedly “temporary” camps in central Rakhine State.[38] IDPs who have been temporarily housed due to previous outbreaks of violence have complained of squalid conditions and uncertain futures, and face almost total restrictions on their movement, access to health care, and education.[39] Crucially, it is uncertain how voluntary whatever repatriation process agreed on between the two countries would ultimately be.

Rohingya refugees installing drainage systems in Kutupalong refugee camp – © MOAS.eu/Dale Gillett 2018

Methodology & Research Implementation

Building on previous research, the objective of this project was to collect and analyse data on refugees’ views and understanding of potential repatriation to Myanmar, from a wide range of adult Rohingya respondents that had arrived in Bangladesh after the August 25th military operation in northern Rakhine State. This research combines quantitative and qualitative methodologies to address the following primary research objectives:

- Demographics

- Quality of life in Bangladesh

- Views on, and knowledge of, repatriation

- Attitudes towards repatriation and willingness to return to Myanmar

Data Collection

Over a three-week period (15 April-6 May 2018), Xchange conducted a cross-sectional survey with Rohingya refugees across 12 official and unofficial refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

The data collection team consisted of four enumerators, two men and two women, all Rohingya refugees themselves and fluent in the Rohingya language. The enumerators administered questionnaires with the use of an online application at two officially registered camps (RC), and 10 other unofficial settlements in Cox’s Bazar:

- Kutupalong RC and its expansion (including Lambashiya and Madhur Chara)

- Balukhali MS and its expansion

- Thangkhali-Burma Para and Mainnerghona

- Hakimpara

- Bagghona-Potibonia

- Jamtoli

- Chakmarkul

- Shamlapur

- Unchiprang

- Leda

- Nayapara RC and its expansion

- Jadimura

Each enumerator interviewed an average of 19 people per day while maintaining constant remote communication with the Xchange research team and guidance from MOAS operational staff on the ground. Their efforts resulted in a total of 1,823 interviews; 1,703 were deemed relevant for further analysis.

The survey design was based on Xchange’s previous reports, literature reviews, and key informant interviews. Three days prior to the official data collection period, the enumerators conducted a pilot testing of the research instrument in Kutupalong RC. Minor changes were made to the questionnaire to facilitate the respondents’ understanding and reduce any potential response bias.

To establish a high level of rapport between interviewers and interviewees and ensure the information received was as unbiased as possible, female enumerators interviewed only women.[40] The two male enumerators interviewed a predetermined number of women (64 in total) in Kutupalong RC, Balukhali, Leda, and Bagghona-Potibonia, and were responsible for interviewing all male respondents. At the end of each working day, the surveys were immediately uploaded to an online platform for review by the coordination team and to minimize data loss.

All surveys were conducted in person in a secluded area to ensure privacy. The principle of confidentiality was explained to all respondents and verbal consent was ensured before proceeding with the survey.

The research instrument[41] included closed-ended (yes/no), open-ended, and multiple-choice questions. Most open-ended questions yielded similar responses, so it was considered appropriate to analyze these responses both quantitatively and qualitatively. In the final section of the survey, respondents were given the option to comment freely on their thoughts about repatriation.

Target Population and Sampling

The research for this project employed a stratified random sampling technique. The underlying target population was estimated to be 317,706 adults (over 18 years old), ‘new Rohingyas’ (those who had arrived in Bangladesh after the events of 25 August 2017), currently resident in refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar district. This number was determined through simple calculations[42] based on the newest data provided by the UNHCR (18 March 2018) at the time of data collection preparation.[43] The data provided by UNHCR gave the researchers the ability to break the population down by refugee camp of residence and gender, reducing opportunities for selection bias to occur. As randomization was applied after the stratification of the entire population, the sample accurately reflects the population under study. Moreover, each subgroup within the population received appropriate representation within the sample and no subpopulation was either over- or underrepresented in the results.

Therefore, the sample of 1,703 respondents can be considered broadly representative of the total adult ‘new Rohingya’ population residing in refugee camps across Cox’s Bazar district. With a sample of 1,703 from a population of 317,706, on a 95% confidence level, the margin of sampling error stands at 2.37.

Limitations

Sampling

As the borders of the expansion zones of the two largest camps in the area (Kutupalong and Balukhali) differed across maps, the whole area of Kutupalong-Balukhali was roughly divided in half during the stratification process.

Even though the enumerators made every effort to select respondents randomly, the majority of interviewees were heads of households, as enumerators went from door to door increasing the likelihood that heads of households would be approached before interviewing others. Furthermore, due to random selection, not all age groups were represented in correspondence with the gender-age group distribution of the total Rohingya population in Cox’s Bazar.

Validity and Reliability

Challenges in validity and reliability were moderated by employing extensively trained enumerators, conducting daily analysis of the uploaded surveys, and holding weekly online meetings to discuss the status of the data collection and solve any difficulties that had arisen during the process.

The enumerators, as Rohingya refugees themselves and fluent in Rohingya, could clarify questions posed by the respondents. However, the questions and the responses were translated from English to Rohingya and from Rohingya to English respectively by each enumerator on the spot. This might have resulted in misinterpretations and/or negatively influenced the accuracy of some responses, despite the good command of English of all enumerators.

Representativeness

The results are generalisable for the whole adult ‘new Rohingya’ population in Cox’s Bazar but not for the population of each camp considered separate from the others. One should be cautious about making inferences from the results for a certain camp or a certain subgroup of individuals across the sample as, due to time constraints, no statistical tests were undertaken, meaning that some of the results might be outcomes of pure chance.

Rohingya refugees weaving shelters out of bamboo in Unchiprang refugee camp – © MOAS.eu/Dale Gillett 2018

Key Findings

Demographics

The Xchange team interviewed a total of 1,703 adult ethnic Rohingyas who fled Northern Rakhine State to Cox’s Bazar District in Bangladesh after the events of 25 August 2017.

Date of arrival: 97% arrived between 25 August and 31 December 2017; 3% arrived in 2018.

Gender: 763 were men (45%); 940 were women (55%)

Gender: 763 were men (45%); 940 were women (55%)

Age: Respondents’ ages ranged between 18–120, with a median of 40 and an average of 40.4 years. The largest age group represented in the survey are 35-39-year-olds. Women were mostly between the ages of 20 and 39, and men were mostly between the ages of 35 and 54. In the youngest and oldest age groups (<20 and 85+ respectively) women were more represented than men.

Place of Origin: As expected, the majority (65%) of respondents came from townships that were heavily targeted by the armed forces in Northern Rakhine State: 65% from Maungdaw, 26% from Buthidaung, 7% from Rathedaung. 1% were from Sittwe (Akyab), the Rakhine State capital, and one person claimed to be from Yangon/Rangoon[44], Myanmar’s largest city and former capital.

Place of Origin: As expected, the majority (65%) of respondents came from townships that were heavily targeted by the armed forces in Northern Rakhine State: 65% from Maungdaw, 26% from Buthidaung, 7% from Rathedaung. 1% were from Sittwe (Akyab), the Rakhine State capital, and one person claimed to be from Yangon/Rangoon[44], Myanmar’s largest city and former capital.

Marital Status & Children: 83% of respondents were married; 4% were Single; 12% were Widowed; and 1% were Divorced. 78% of the respondents stated that they have children in Bangladesh.

Household size: 79% of the sample were heads of households. Only 2.3% live with one or two other people, while more than half of the respondents (54%) live in cramped conditions, in households of seven to ten people.

Household size: 79% of the sample were heads of households. Only 2.3% live with one or two other people, while more than half of the respondents (54%) live in cramped conditions, in households of seven to ten people.

Life in Myanmar

Education

Only one in three (34%) respondents received an education in Myanmar. In the sample, ten people were holders of a bachelor’s degree. Two held Master’s degrees. One in five (20.6%) had received their Burmese Secondary Education Certificate. One in five (21.8%) received education in madrasas.

Rohingyas residing in Rakhine State have limited access to education; primary school enrolment and completion rates are among the lowest in the country; secondary education is nearly non-existent. This is due to a number of factors, including mobility restrictions, sub-par school facilities, high levels of poverty, limited teacher training, and the inability of parents to pay school fees.[45] These factors have only worsened since the 2012 violence.

Employment

Employment

Waves of inter-communal violence in Rakhine State in 2012 divided communities and disrupted trade and commerce as well as any trade across the border with Bangladesh. Discrimination against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine resulted in very low employment among the Rohingya population. In addition to this, mobility restrictions have made it difficult to find employment outside of their immediate surroundings.[46]

As expected, most respondents (87%) were not previously employed in Myanmar; 12% (11% men and 1% women) had a job. Of those respondents:

- 17% worked for an NGO (unspecified job excluding teachers),

- 14% were teachers (NGO/Madrasa/School),

- 12% worked at a shop,

- 12% worked at a company or had their own business,

- 6% were farmers,

- 5% worked at a mosque or madrasa,

- 5% did housework (e.g. maid),

- 5% worked in the health industry (i.e. doctor, midwife, pharmacist, nurse),

- 4% worked at a restaurant,

- 3% were drivers,

- the rest (17%) did various other jobs (e.g. secretary, clerk, fisherman, shopkeeper, tailor).

Despite this, 49% of our respondents stated that they had at least one skill/profession (e.g. tailoring, sewing, fishing, farming, driving, grocery business, etc.).

- 66% of the female respondents were skilled in tailoring, sewing, and/or embroidery. Four women in the sample had IT knowledge.

- 23% of male respondents were farmers, and an additional 32% could cultivate land. 17% were either fishermen, made fishing nets, or ran a business selling fish.

Life in Bangladesh

Overall, 98.65% of adult Rohingyas in our sample felt welcome in Bangladesh; no respondent from Jadimura, Jamtoli, Nayapara, Potibonia/Baghonna, and Shamlapur felt unwelcome in Bangladesh. Of the 23 people who did not feel welcome, the majority (eight individuals or 35%) live in Kutupalong.

This feeling of being welcome in Bangladesh could be due to a number of factors, such as Bangladesh’s historical reception of the Rohingya fleeing from Myanmar, the provision of humanitarian relief and services with the help of international organisations, and the overall feeling of security compared to their precarious existence in Myanmar

Feelings of safety

During the day:

99.41% of respondents stated that they feel safe during the day in the refugee camps.

The remaining ten respondents who did not feel safe during the day described the following reasons: the climate during the summer season (hot weather that causes discomfort in cramped conditions) and wild animals. Interestingly, eight of the ten people that claimed to not feel safe were men.

During the night:

95.89% felt safe during the night in the refugee camp. Of those who did not feel safe, 80% (54) were women. The individuals who did not feel safe specified the following reasons:

- wild animals, particularly elephants

- potential robbery

- “murderers”

- human traffickers

Interestingly, 41% (33) of the people interviewed in Leda camp did not feel safe during the night, due to potential fires and wild animal attacks at any time. This may be explained by tragic events that have occurred recently in Leda camp, including camp fires.[47] Deaths from elephant trampling are also common, as the camp sits on an elephant passage through the forest.[48] A few people mentioned fearing to sleep at night, as they hear gunshots.

“We are facing different kinds of problems here, like robbery. We can’t sleep here peacefully, because gangs of thieves shoot guns at night. How could we sleep?”

29-year-old Rohingya woman

Integration into the camps and host communities

79.57% of the respondents stated that they had made new Rohingya friends (other than family) after arriving in Bangladesh.

79.57% of the respondents stated that they had made new Rohingya friends (other than family) after arriving in Bangladesh.

91% of male respondents stated they had made new Rohingya friends compared to 70% of women, reflecting the fact that men in the camps are more likely to be outside their household and in social spaces.

16% (273 people) stated they had made at least one Bangladeshi friend. No respondents from Nayapara or Jadimura had made Bangladeshi friends. Anecdotal evidence indicates women are more likely than men to interact with the local Bangladeshi neighbours or hosts.

16% (273 people) stated they had made at least one Bangladeshi friend. No respondents from Nayapara or Jadimura had made Bangladeshi friends. Anecdotal evidence indicates women are more likely than men to interact with the local Bangladeshi neighbours or hosts.

92.78% of all respondents stated that there is a strong sense of community in the refugee camps:

- 100% of respondents from Chakmarkul

- 98% of respondents from Thangkhali

- 96% of respondents from Nayapara

Notably, 11.75% (43) of the interviewees from Kutupalong did not feel a strong sense of community there. This could be due to the camp’s large size, which accommodates over half of the Rohingya population in Cox’s Bazar District.[49]

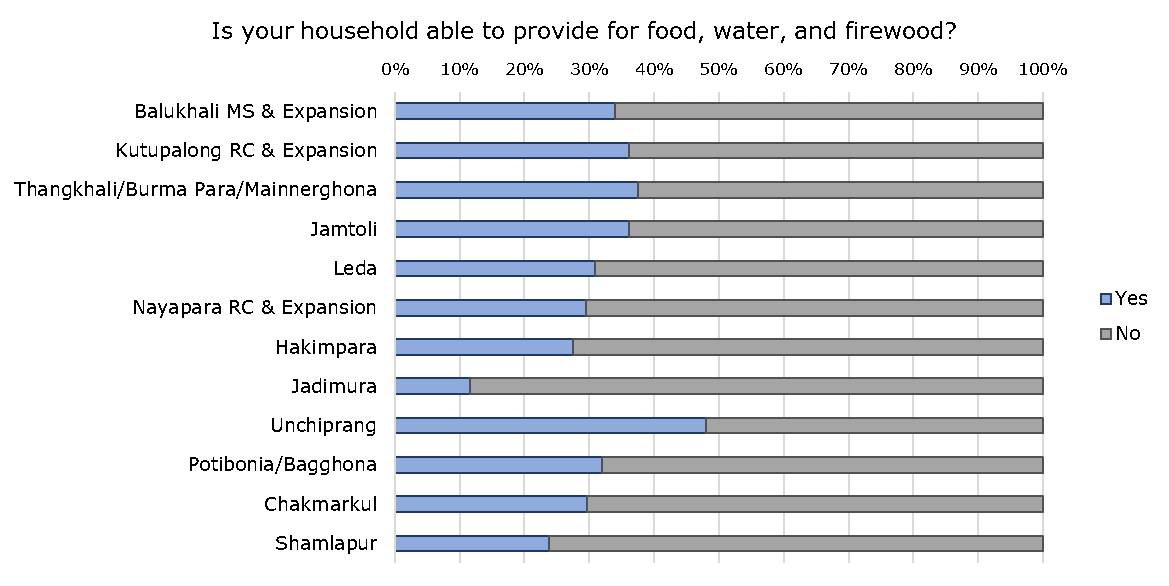

Provision of everyday needs

66% of all respondents did not feel they were able to provide essentials such as food, water, and firewood for their households. This could be due to limited resources in the camps, the need to survive on government and humanitarian provisions, and a lack of livelihood opportunities.

Livelihoods & Employment

Livelihoods & Employment

90% of the respondents were not engaged in any employment. Of the 168 respondents that did have a job, 146 (87%) were satisfied with their job. This is likely to be because Rohingyas struggle to access formal, legal, employment due to the lack of recognition as refugees by the Bangladeshi government, yet as indicated in the previous survey question, have unfulfilled household needs. This was also recognized in our previous Snapshot Survey, which indicated that respondents were surviving by selling food and non-food items, as well as engaging in occasional casual work around the camps.[50]

Of those who were looking for a job, 41% would be happy to have any kind of job and 33% reported that they would like to work for an (I)NGO/charity. This demonstrates the strong desire for any kind of employment, as well as the most common types of contracting within the camps (contracted to work for humanitarian organisations or charities).

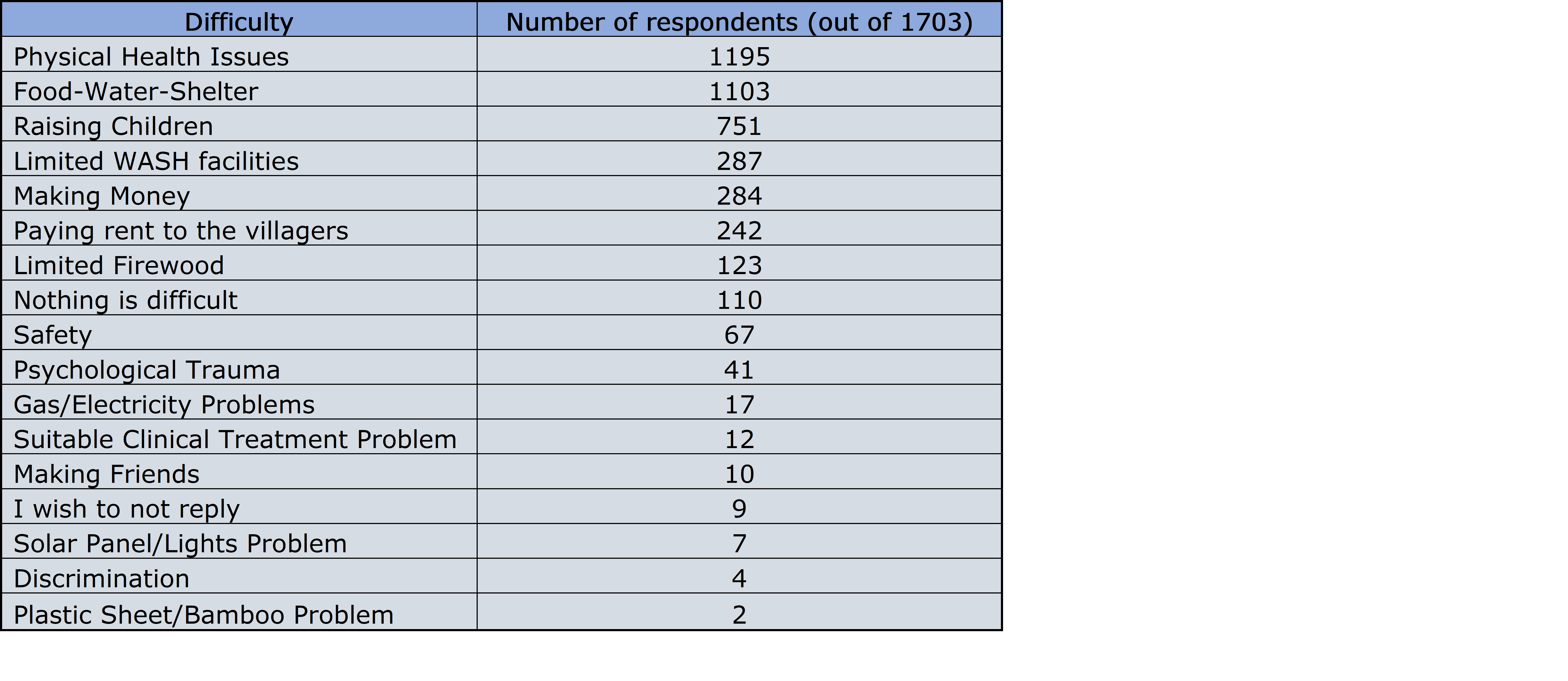

Difficulties living in Bangladesh

Difficulties living in Bangladesh

When respondents were asked to choose the three most difficult aspects of life in Bangladesh for themselves and their family, 70% of the respondents stated ‘health issues’. This is indicative of both the previous living conditions and limited healthcare available in Myanmar,[51] as well as the possible consequences of the military crackdown, which left scores of Rohingya injured before coming to Bangladesh.[52]

Providing the family with adequate food, water, and shelter was reported as a critical issue by 65% of respondents and corroborates data from earlier survey questions on family provisions.

“In Bangladesh We are not getting enough food, water, and shelter. Every month we have to pay rent for the land where we have built our houses. It’s difficult to pay the money; we don’t have any way to make money. So, I would like to request from the UN to solve our problem before repatriating us without safety.”

18-year-old Rohingya woman

44% mentioned that raising children is one of the most difficult things for them; 96% of respondents that highlighted this issue were women. These responses could be due to the previous traumas they experienced in Myanmar, a lack of educational and recreational facilities – particularly for children over primary school age – as well as perceived dangers in cramped camp conditions.[53]

Only 6.5% claimed to find nothing difficult about life in Bangladesh. Of those, 91% were men.

Knowledge and Perceptions of Repatriation

Knowledge and Perceptions of Repatriation

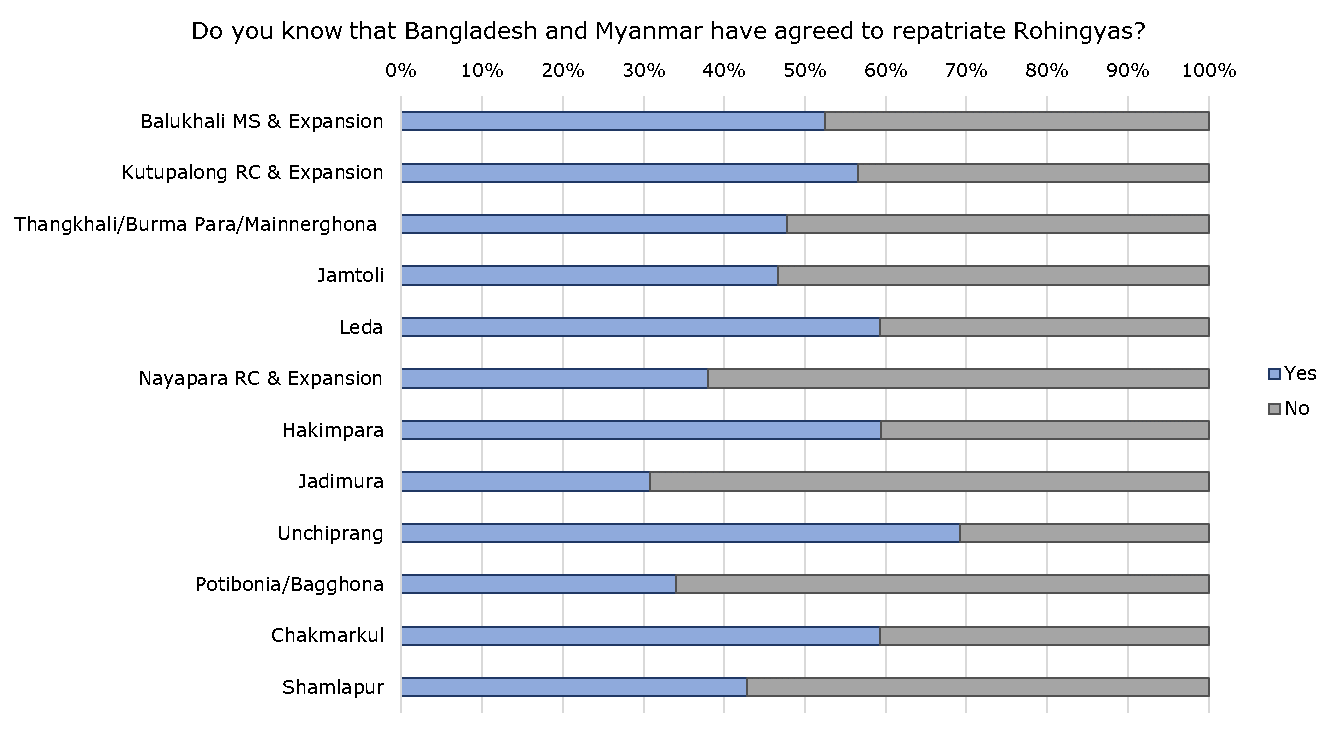

Overall knowledge of repatriation

When respondents were asked about their knowledge of the repatriation agreement between Bangladesh and Myanmar, only 51.6% had heard about it; 57% of male respondents and 47% of female respondents, respectively.

When respondents were asked about their knowledge of the repatriation agreement between Bangladesh and Myanmar, only 51.6% had heard about it; 57% of male respondents and 47% of female respondents, respectively.

In Jamtoli, Jadimura, Baghonna/Potibonia, Shamlapur, Thangkhali, and Nayapara camps, there were more respondents without knowledge than with knowledge of the repatriation agreement.

In Jamtoli, Jadimura, Baghonna/Potibonia, Shamlapur, Thangkhali, and Nayapara camps, there were more respondents without knowledge than with knowledge of the repatriation agreement.

Knowledge of repatriation: how?

Those respondents who knew about the agreement were asked how they first heard about it. The most common means by which respondents had heard that an agreement had been signed (40%) was through the media (internet, radio, TV). This was mostly the case for men; women relied more on word of mouth via family, neighbours, or friends. This is likely because men have better access to media and social spaces, and women typically spend more time engaged in chores around their homes.

Those respondents who knew about the agreement were asked how they first heard about it. The most common means by which respondents had heard that an agreement had been signed (40%) was through the media (internet, radio, TV). This was mostly the case for men; women relied more on word of mouth via family, neighbours, or friends. This is likely because men have better access to media and social spaces, and women typically spend more time engaged in chores around their homes.

Knowledge of repatriation: why?

When respondents were asked whether they understand why the government of Bangladesh wants to repatriate them, 94.5% of those who had knowledge of repatriation, did not have a clear picture of why it was occurring.

The remainder (5.5%, or 48 people) were asked to give their explanation as to why they think repatriation was being discussed at this point in time. Here, their opinions varied. Some supported the notion that Bangladesh could not afford to take care of Rohingyas due to its large population; others mentioned that talk of repatriation may just be media propaganda, while many stated that it is a “human business” between the two countries and/or that their ultimate plan is to kill all Rohingyas.

“Myanmar wants to kill us all. They have been killing us for many years. I think, they have planned to cleanse us all.”

29-year-old Rohingya woman

On the other hand, some respondents were optimistic, stating that the Myanmar government might have agreed to repatriation because they truly want to give Rohingyas their nationality and rights.

“I think that the government of Myanmar has agreed to accept us as Rohingya and they want to give us nationality, freedom, and opportunities.”

49-year-old Rohingya woman

This could indicate possible information transfer issues from authorities and international organisations on repatriation. The low comprehension figures and overwhelming lack of clarity reported by respondents is extremely concerning, as repatriation should be voluntary in nature and decided with full knowledge of the process and consequences.

Cooperation between governments and the current situation in Rakhine State

Cooperation between governments and the current situation in Rakhine State

62% of respondents believed that the governments of Bangladesh and Myanmar were not cooperating well on the situation of the Rohingyas. Women were divided equally on this matter, whereas 76% of the male respondents believed that the cooperation is inadequate.

74% of respondents had not received any information about the current situation in Rakhine State. 31% of women believed they knew the current condition in Rakhine State, compared to 19% of the total population of men. Many respondents thought that the situation there is still the same, i.e. that the security forces continued to burn homes and that mobility was still extremely restricted. Some respondents mentioned that every day they hear stories of their neighbours being killed. One respondent mentioned that they heard the Myanmar authorities told current Rohingya residents of Rakhine State that they had to accept the National Verification Card (NVC), which does not grant them full citizenship, but may allow them increased mobility rights and access to services.[54]

“I think, they [the government and military of Myanmar] don’t think that we are also humans.”

33-year-old Rohingya woman

“At our village in Rakhine State, people can’t move anywhere.”

28-year-old Rohingya man

“I’m hearing from my neighbours that Myanmar military and police are still torturing Rohingya. They do not allow them to move freely nor receive educations.”

23-year-old Rohingya woman

Timing

78% of respondents believed that repatriation would eventually happen in the next two years. This could be due to memory of previous repatriation/refoulment processes undertaken by the two governments that, despite taking long periods of time, resulted in the return of large numbers of Rohingya back to Myanmar. However, older respondents who lived through the 1978 and 1991 repatriation efforts expressed their concerns.

“I have been hearing about murders kept secret by Myanmar military and Myanmar people for many years. In this age I have become a refugee in Bangladesh three times. Every time, they – the Myanmar government – said they will not torture us anymore but after returning they always start killing and looting properties of Rohingya people.”

97-year-old Rohingya woman

Satisfaction with information received

80% of respondents did not feel satisfied with the level of information they had been receiving regarding the repatriation process. This was mostly due to there being no information provided regarding their rights, citizenship, and their ability to exercise their religious freedom back in Myanmar. The majority expressed a desire to know if upon return they will be provided with equal rights.

“[I am not satisfied] because I heard that Myanmar wants to accept us as Bengali. We are not Bengali. We are Rohingya. We want our native name as Rohingya.”

23-year-old Rohingya woman

“In Bangladesh, all religions have equal rights. Here there are no differences between Muslims, Hindus, or Buddhists. We want equal rights just like in Bangladesh.”

27-year-old Rohingya woman

The respondents wanted to know more about their own rights from the international community and the United Nations, and whether they would be living in internment camps inside Myanmar or whether they would be provided with land again.

“I’m not satisfied with the level of repatriation. Because Myanmar wants to keep us in camps.”

55-year-old Rohingya woman

Justice and involvement of the international community

The respondents desired those who killed their loved ones and burned their properties be brought to justice. Respondents asked for the UN Security Council to stand by them and urged that those responsible for crimes in Myanmar be brought to the International Criminal Court (ICC). Respondents feared there was a plan to commit the same atrocities they had already been subjected to upon their return and questioned why Myanmar is willing to let them do so considering the number of Rohingyas that had been killed already.

“I’m a Rohingya girl. I think every human has the right to live in this world without fearing their own country’s government. I would like to call the UN to give us justice for genocide and give us our country.”

19-year-old Rohingya woman

“I still have some relatives in Myanmar. Sometimes they call us and cry for us to save them. They said many times that Myanmar military and people are looting and killing them one by one.”

60-year-old Rohingya woman

“The Myanmar military raped me when I was fleeing from Myanmar to save my life. A whole group of military people; they all raped me. That time I became senseless. I don’t want to return to Myanmar without my identity as a Rohingya.”

21-year-old Rohingya woman

Conditions for repatriation

“I could return to Myanmar, but how? Myanmar tells the Rohingya: “You are Bangladeshi!” and Bangladesh tell us here: “You are Burmese!”. Where is our country? Please introduce us to where in the world our land is.”

65-year-old Rohingya man

Overall, 97.5% of the Rohingya population would consider returning to Myanmar. Almost all the respondents (99%), however, mentioned that they would go back only if certain conditions were met, with the majority mentioning citizenship of Myanmar with acknowledgement that they are Rohingya, freedom of movement and religion, and their rights and dignity restored.

“If we go back again without justice, the Myanmar government will play as like football. How can we go back without freedom?”

40-year-old Rohingya woman

Of the respondents who considered going back to Myanmar in the future:

- 99% would return to the same township they were living in before the move.

- Only five people (0.31%) stated that they would return unconditionally, whereas the vast majority (99.69%) would consider returning only after certain conditions were met (e.g. nationality, citizenship, freedom of movement, equal rights with other peoples of Myanmar, religious freedom).

However, 40 individuals (36 of whom women) categorically refused to ever go back to Myanmar.

“I don’t want to return! I don’t have any condition to return. It’s better to resettle me from Bangladesh to another country. It’s better if we die than return.”

36-year-old Rohingya woman

In addition to this, respondents wanted their identity documents, properties and businesses back which were taken by the military:

“We want nationality and freedom. We weren’t homeless in Myanmar; we have homes, lands, and properties. The Myanmar military destroyed all our homes and lands. We want our properties before returning to Myanmar.”

23-year-old Rohingya woman

“If Myanmar will return my properties which were looted by the military and Myanmar peoples. They killed my husband. I want justice for my husband. I want citizenship of Myanmar. If the Myanmar government will accept my demands then I will go back to Myanmar.

48-year-old Rohingya woman

Respondents requested equal opportunities to other Myanmar citizens, and their rights to education and employment opportunities for themselves and their loved ones:

“We want citizenship of Myanmar. After returning to Myanmar, we don’t want to live like refugees anymore. Myanmar is our country. I have the right to get the citizenship and freedom of any kind in Myanmar.”

19-year-old Rohingya woman

“We want nationality and equal rights. We also want to be like the Rakhine people; we want equal rights with them. If they have freedom of movement, education, treatments etc., then we must have those opportunities.”

23-year-old Rohingya woman

Respondents demanded that the government of Myanmar “stops genocide and rape” before they return. In this regard, respondents asked for the UN to oversee their return to ensure their security. They also demanded sanctions be placed on the Myanmar government.

However, 69.8% of respondents did not believe that the Myanmar government would eventually recognise their rights. 30.1% were more optimistic. Men were more pessimistic than women in general (87% of men compared to 55% of women).

A few respondents mentioned they had been refugees in Bangladesh more than once before. After their previous repatriations, they witnessed the same kind of atrocities being committed. The respondents’ trust in Myanmar could therefore not be restored without receiving confirmation of their rights in advance.

“I became a refugee in Bangladesh three times. The first time, the Myanmar government said that they won’t torture Rohingyas anymore. But they didn’t keep their promise. This time I want to return safely with dignity.”

81-year-old Rohingya woman

There was a large disparity between camps over the belief that their rights will be recognised in Myanmar if they return; overall, interviewees from the south (Nayapara (98.6%), Jadimura (96%), Shamlapur (85%), Baghonna (98%)) were pessimistic, with more than four in five respondents believing that the Myanmar government would never recognise their rights. In Chakmarkul and Unchiprang, however, more respondents believed their rights would be recognised (52% and 54% of each camp’s respondents respectively).

There was a large disparity between camps over the belief that their rights will be recognised in Myanmar if they return; overall, interviewees from the south (Nayapara (98.6%), Jadimura (96%), Shamlapur (85%), Baghonna (98%)) were pessimistic, with more than four in five respondents believing that the Myanmar government would never recognise their rights. In Chakmarkul and Unchiprang, however, more respondents believed their rights would be recognised (52% and 54% of each camp’s respondents respectively).

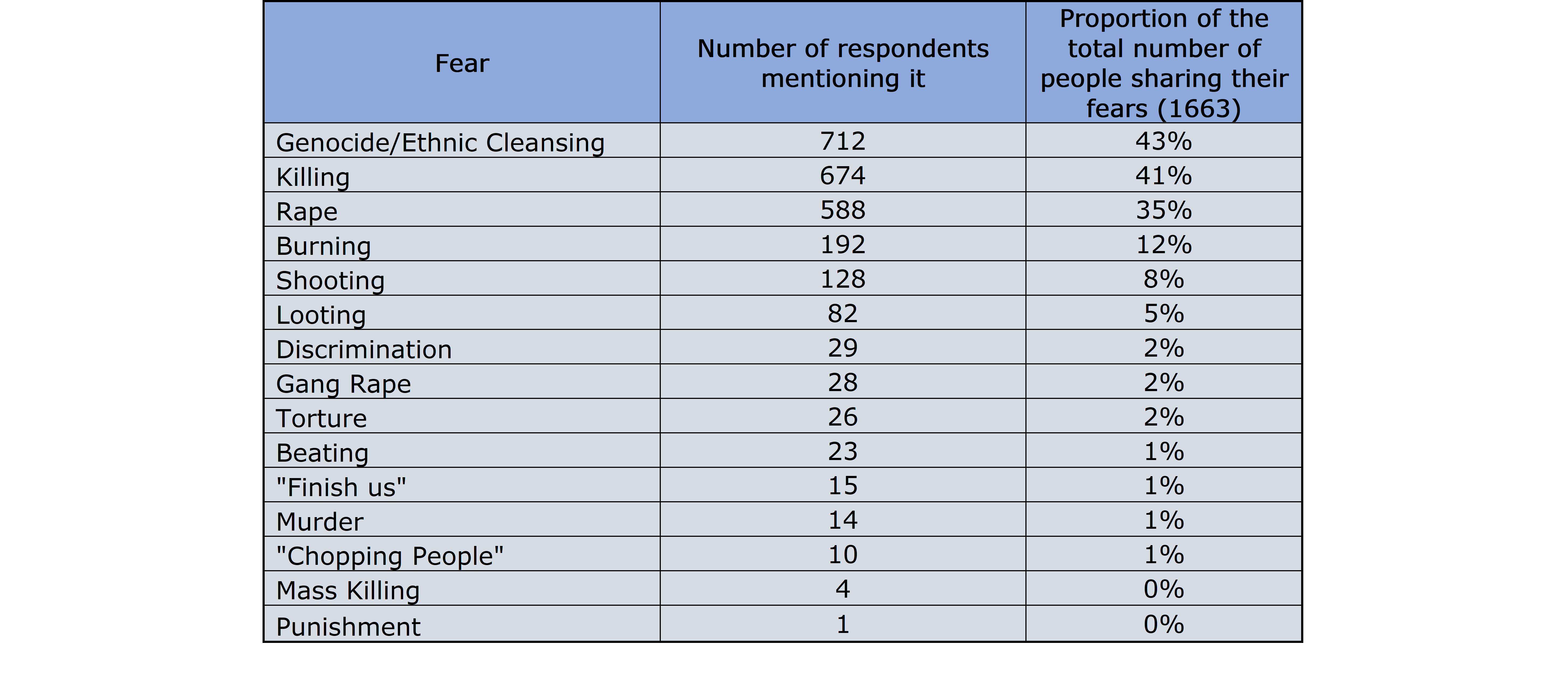

Biggest fears upon returning

97.77% of respondents feared returning to Myanmar. Of these, almost all (98.98%) believed that they would face discrimination upon their return. In addition to whether they expected to be discriminated against, respondents were given the opportunity to openly share their biggest fears about returning to Myanmar. The most common responses included the following:

Some respondents specified who they were afraid of: 16% specified the Myanmar government, 13% the ethnic Rakhine people/Buddhists, 13% the Myanmar military.

Some respondents specified who they were afraid of: 16% specified the Myanmar government, 13% the ethnic Rakhine people/Buddhists, 13% the Myanmar military.

“The government of Myanmar and the Rakhine people will always discriminate us. It might be better for us to hang ourselves.”

28-year-old Rohingya woman

Most people’s fears can be seen to be derived from their previously lived or witnessed traumatic experiences, including rape, torture, and the murder of adults and children, among other incidents.

“My biggest fear is this: while returning to Myanmar, the [Myanmar] military will start chopping people and then a stream of blood in my village…”

70-year-old Rohingya man

“Chopping people piece by piece and raping children in front of me; this is my biggest fear about returning to Myanmar.”

45-year-old Rohingya man

“I’m very afraid to go back because of shooting, raping, killing, and burning infants in front of us.”

75-year-old Rohingya man

Feelings towards the future

With reference to their views of the future, nine in ten Rohingyas (91%) felt positive about their own (and their families’) future in Bangladesh. However, 96.94% did not want to stay in Bangladesh permanently.

“We don’t want to stay in Bangladesh permanently because Myanmar is our motherland. We want freedom, Rohingya citizenship, equal rights, and free movement.”

40-year-old Rohingya woman

Many explained that their freedom and resources are extremely limited in the camps, so they cannot restore their livelihoods in Bangladesh. Others said that they did not want to live in Myanmar nor Bangladesh; they wanted to be resettled in third countries where their safety could be guaranteed.

“In Bangladesh we are facing many problems like safety, not enough food, water, and firewood. [Hence,] we are not allowed to live freely either in Bangladesh or Myanmar.”

44-year-old Rohingya woman

52 individuals (3% of the total) would consider staying permanently in Bangladesh if the following conditions were met: 94% (49) wanted free movement, 71% (37) wanted citizenship and identification documents, 52% (27) wanted education options, 17% (9) wanted housing, and 13% (7) wanted employment options. Some (26.9%) wanted all three: citizenship, free movement, and education options. There were a handful of respondents who said they would be willing to stay in Bangladesh even if these conditions went unmet.

Plans upon returning

The majority of respondents who planned to return to Myanmar wished to continue their education, take up some type of training or continue farming and create a business. This included continuing as farmers, or to be trained in other skills, such as in tailoring or IT. Most female respondents considered their children’s educations as a top priority.

However, some respondents held little hope around the prospect returning. The oldest interviewees were pessimistic about their capabilities due to their advanced ages. A few respondents said they would only think about their futures after returning to Myanmar. Other respondents just wanted to return and find peace of mind before considering their futures.

“I have no [future] plans before going back to Myanmar and this is because we lost everything; the Myanmar government finished what we had.”

45-year-old Rohingya woman

“We could die in Bangladesh, but we do not agree to go to Myanmar without justice.”

28-year-old Rohingya woman

Rohingya refugee carries firewood in Unchiprang refugee camp – © MOAS.eu/Dale Gillett 2018

Conclusion

In the wake of the August 25 attacks, hundreds of thousands of Rohingyas from Rakhine State were forced to flee their homes across the border to Bangladesh. Most had witnessed, or experienced themselves, grave human rights abuses at the hands of the Myanmar military and Buddhist Rakhine extremists, including entire villages being razed, mass shootings, sexual abuse of women and children, and children being murdered.

Building on Xchange’s previous research, the objective of this survey was to collect and analyse, data from adult Rohingyas that had arrived in Bangladesh after the events of August 25th in northern Rakhine State, Myanmar. Our research objectives were to better understand the demographics, quality of life in Bangladesh, views, knowledge and attitudes towards repatriation and the willingness of the refugee population to return to Myanmar.

The Xchange team interviewed a total of 1,703 ethnic Rohingya across Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. As expected, most respondents came from townships that were heavily targeted by the armed forces in northern Rakhine State, particularly Maungdaw (65%), Buthidaung (26%), and Rathedaung (7%). The Rohingya interviewed for this survey faced discrimination and denial of their basic rights in Myanmar. This was evident by the number of respondents (34%) that stated they had not received any kind of education or ability to have a livelihood in their places of origin (87%). This is despite nearly half of our respondents stating that they had a skill or profession.

Rohingyas living in camps across Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, face insurmountable daily struggles. 61% live in cramped conditions, with restricted mobility, limited access to education for their children. The majority (66%) felt they were largely unable to provide for their family’s daily needs. Despite this, they felt almost universally welcome and safe in Bangladesh, with a strong sense of community. These responses could be due to an overall sense of well-being that the Rohingya did not previously enjoy in Myanmar, where they faced constant persecution and insecurity. Tellingly, however, very few respondents had made Bangladeshi friends, possibly due to the isolation of many of the refugee camps, restricted mobility, and the Bangladeshi Government’s policy of non-integration with a view to repatriation. Almost all respondents did not wish to stay in Bangladesh permanently (97%).

This most recent repatriation agreement between the Bangladesh and Myanmar governments marks the third major instance since the 1970s where Bangladesh has attempted to repatriate Rohingyas expelled from Myanmar by the Myanmar government, making the sustainability of the Bangladesh Government’s “temporary” approach to the Rohingya issue questionable. Crucially, the repatriation deal failed to consult the Rohingya or outline what conditions they may face upon their return. In addition to this, only half (51.6%) of total respondents (57% of male and 48% of female) had heard about the proposed repatriation deal between Myanmar and Bangladesh in any capacity. When asked whether they understood why the government of Bangladesh wants to repatriate them, 94.5% of those who had knowledge of repatriation did not have a clear picture of why it might occur.

Understandably, 80% of respondents did not feel satisfied with the level of information they had received regarding the repatriation process. The majority expressed a desire to know if, upon their return, they would be provided with equal rights, citizenship, and the ability exercise of their religious freedom. Moreover, 74% of respondents had not received any up-to-date information about the current situation in Rakhine State, where many Rohingyas continue to face unimaginable traumas. This is reflected in the fact that 70% of respondents did not believe that the Myanmar government would recognise their rights upon return and almost all (98%) feared returning, citing genocide/ethnic cleansing (43% of the population), rape (41%), and killing (35%) as issues of concern.

78% of Rohingya respondents believed that repatriation would happen in the next two years, despite the governments of Bangladesh and Myanmar not cooperating well on the situation (62%). Overall, 97.5% would consider returning to Myanmar, and almost all of those (99%) indicated that they would like to return to the same township they were living in before they were forced to flee. However, only 5 respondents (0.31%) expressed that they would be willing to return unconditionally, whereas the clear majority (99.69%) would consider returning only if certain conditions are met.

When asked, most respondents’ conditions for return included basic human rights and dignity, citizenship, freedom of movement and religion, and justice for the horrors they endured. Thus, while the eventual return of Rohingya refugees to their homeland voluntarily and in full dignity is desirable, Rohingyas themselves must be consulted in the repatriation process, and certain conditions must be met by the Myanmar Government before their safe return can be considered.

“We ask the United Nations: when are we going to get our justice?”

46-year-old Rohingya man

Footnote

[1]Inter Sector Coordination Group, ‘SITUATION REPORT: ROHINGYA REFUGEE CRISIS Cox’s Bazar’ (10 May 2018) available at: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/20180510_-_iscg_-_sitrep_final.pdf

[2] Gabriella Canal, ‘Rohingya Muslims Are the Most Persecuted Minority in the World: Who Are They?’ Global Citizen (10 February 2017) available at:

https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/recognizing-the-rohingya-and-their-horrifying-pers/

[3] UNHCR (2018). Mixed Movements in South-East Asia. [online] Available at: https://unhcr.atavist.com/mm2016 [Accessed 16 May 2018].

[4] Xchange Foundation, Rohingya Survey 2017 (November 2017) available at: http://xchange.org/reports/TheRohingyaSurvey2017.html

[5] Human Rights Watch, ‘Burma/Bangladesh: Return Plan Endangers Refugees: Repatriated Rohingya Would Face Abuse, Insecurity, Aid Shortages’ (23 January 2018) available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/01/23/burma/bangladesh-return-plan-endangers-refugees

[6] ABC News, ‘Myanmar’s claim of first Rohingya refugee repatriation disputed by Bangladesh and aid agency’ (16 April 2018) available at: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-04-16/bangladesh,-unhcr-dispute-myanmars-rohingya-repatriation-claim/9661722

[7] Zeba Siddiqi, ‘Bangladesh says start of Rohingya return to Myanmar delayed Thompson Reuters’ (22 January 2018)

[8] UNHCR, ‘Bangladesh and UNHCR agree on voluntary returns framework for when refugees decide conditions are right’ (13 April 2018) available at: http://www.unhcr.org/news/press/2018/4/5ad061d54/bangladesh-unhcr-agree-voluntary-returns-framework-refugees-decide-conditions.html

http://www.unhcr.org/news/press/2018/4/5ad061d54/bangladesh-unhcr-agree-voluntary-returns-framework-refugees-decide-conditions.html

[9] Serajul Quadir, Stephanie Nebehay, ‘Bangladesh, UNHCR to ink preliminary plan on Rohingya repatriation’ Thomson Reuters (11 April 2018) available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-rohingya-bangladesh-un/bangladesh-unhcr-to-ink-preliminary-plan-on-rohingya-repatriation-idUSKBN1HI2QR

[10] Xchange Foundation, Rohingya Snapshot Survey 2018 (February 2018) available at: http://xchange.org/snapshot-survey/

[11] For more information see: Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, TOWARDS A PEACEFUL, FAIR AND PROSPEROUS FUTURE FOR THE PEOPLE OF RAKHINE Final Report of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State (August 2017) available at: http://www.kofiannanfoundation.org/app/uploads/2017/08/FinalReport_Eng.pdf

[12] The 13 demands given to the UN se included “citizenship” and equal rights; that the nationality card will be issued to them before repatriation; the Myanmar government ensures improved law and order situation for all Rohingya; the UN and ICC are involved in this repatriation process; their original land in the Arakan (Rakhine) state is returned to them; ICC brings them justice against those gang-rape, killing, and destruction of properties; and the UN fact finding missions and the investigation teams are allowed to investigate the details of August 2017 incidents. See: Zeba Siddiqui, ‘Exclusive: Rohingya refugee leaders draw up demands ahead of repatriation’ Thomson Reuters (19 January 2018) https://www.reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-rohingya-petition-exclusive/exclusive-rohingya-refugee-leaders-draw-up-demands-ahead-of-repatriation-idUSKBN1F80SE

[13] United Nations Office for the High Commissioner on Human Rights, ‘Report of OHCHR Mission to Bangladesh: Interviews with Rohingyas fleeing from Myanmar since 9 October 2016’ (3 February 2017) available at: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/MM/FlashReport3Feb2017.pdf

[14] Amnesty International, “Caged without a Roof”: Apartheid in Myanmar’s Rakhine State (2017) available at: https://www.amnestyusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Caged-without-a-Roof-Apartheid-in-Myanmar-Rakhine-State.pdf

[15] Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights, Flash Report: Report of OHCHR mission to Bangladesh, Interviews with Rohingyas fleeing from Myanmar since 9 October 2016 (3 February 2017) available at: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/MM/FlashReport3Feb2017.pdf

[16] Human Rights Watch, “All You Can Do is Pray”: Crimes Against Humanity and Ethnic Cleansing of Rohingya Muslims in Burma’s Arakan State (2013) available at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2013/04/22/all-you-can-do-pray/crimes-against-humanity-and-ethnic-cleansing-rohingya-muslims

[17] International Crisis Group, ’Myanmar’s Rohingya Crisis Enters a Dangerous New Phase’ (7 December 2017) available at: https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar/292-myanmars-rohingya-crisis-enters-dangerous-new-phase

[18] Inter Sector Coordination Group, Humanitarian Response Plan 2017: September 2017-February 2018: Rohingya Refugee Crisis (October 2017) pg 9 available at: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/bangladesh

[19]UNOCHA, ‘Rohingya Refugee Crisis’ available at: https://www.unocha.org/rohingya-refugee-crisis

[20] Human Rights Watch, Burma (2000) available at: http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs/Abrar-repatriation.htm

[21] Human Rights Watch, Burma (2000) available at: http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs/Abrar-repatriation.htm

[22] Human Rights Watch, “All You Can Do is Pray”: Crimes Against Humanity and Ethnic Cleansing of Rohingya Muslims in Burma’s Arakan State (2013) available at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2013/04/22/all-you-can-do-pray/crimes-against-humanity-and-ethnic-cleansing-rohingya-muslims

[23] Human Rights Watch, Burma (2000) available at: http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs/Abrar-repatriation.htm

[24] Rock Ronald Rozario, ‘Rohingya repatriation plan not sustainable: Plan to send refugees back to Myanmar lacks foresight as they are still unwelcome in Rakhine State’ UCANews (9 March 2018) available at: https://www.ucanews.com/news/rohingya-repatriation-plan-not-sustainable/81611

[25] Rock Ronald Rozario, ‘Rohingya repatriation plan not sustainable: Plan to send refugees back to Myanmar lacks foresight as they are still unwelcome in Rakhine State’ UCANews (9 March 2018) available at: https://www.ucanews.com/news/rohingya-repatriation-plan-not-sustainable/81611

[26] Article 13(2) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the European conventions for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental freedoms at Article 2, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination at Article 5, the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights at Article 12, and the American Conventions on Human Rights at Article 22.

[27] UN General Assembly, Statute of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 14 December 1950, A/RES/428(V), available at: http://www.unhcr.org/4d944e589.pdf

[28] Art. 8.c of UN General Assembly, Statute of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 14 December 1950, A/RES/428(V), available at: http://www.unhcr.org/4d944e589.pdf

[29] Xchange Foundation, Rohingya Survey 2017 (November 2017) available at: http://xchange.org/reports/TheRohingyaSurvey2017.html

[30] Xchange Foundation, Rohingya Survey 2016 (2016) available at: http://xchange.org/map/RohingyaSurvey.html

[31] Xchange Foundation, Rohingya Survey 2017 (November 2017) available at: http://xchange.org/reports/TheRohingyaSurvey2017.html

[32] Our Snapshot Survey indicated that most adults in Shamlapur and Unchiprang refugee camps spent their days collecting food, water, and firewood (70%), helping out with household chores (61%), praying five times a day and reading the Holy Quran (57%), as well as taking care of their children (53%)

[33] Xchange Foundation, Snapshot Survey: An Insight into the Daily Lives of the Rohingya in Unchiprang & Shamlapur (March 2018) available at: http://xchange.org/snapshot-survey/

[34] “Not to forcibly return anyone to a place where they would face persecution, torture, ill-treatment, or death. Governments cannot pressure individuals to return to a country where they face serious risk of harm.” For more see: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Advisory Opinion on the Extraterritorial Application of Non-Refoulement Obligations under the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol (26 January 2007) available at: http://www.unhcr.org/4d9486929.pdf

[35] http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs/Abrar-repatriation.htm

[36] Rock Ronald Rozario, ‘Rohingya repatriation plan not sustainable:

Plan to send refugees back to Myanmar lacks foresight as they are still unwelcome in Rakhine State’ UCANews (9 March 2018) available at: https://www.ucanews.com/news/rohingya-repatriation-plan-not-sustainable/81611

[37] Satellite images analysed by Human Rights Watch show a 100-kilometre-long area in Rakhine State razed by fires following the crackdown. This area is five times larger than where burnings by Myanmar security forces occurred from October to November 2016. See: https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/09/02/burma-satellite-images-show-massive-fire-destruction

[38] Human Rights Watch, ‘Burma/Bangladesh: Return Plan Endangers Refugees’ (23 January 2018) available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/01/23/burma/bangladesh-return-plan-endangers-refugees

[39] John Zaw, ‘No respite for Rohingya in resettlement areas: Embattled Muslim group shunted from squalid IDP camps to new homes in Myanmar befouled by poor sanitation and sewage’ UCA News (9 May 2018) available at: https://www.ucanews.com/news/no-respite-for-rohingya-in-resettlement-areas/82256

[40] For the purpose of this study, more women were intentionally queried than men. See ‘Target Population and Sampling’ below.

[41]Which can be found in Appendix B.

[42] Population arrived after 25 August 2018: 706,013 (45% over 18, 20% adult males, 25% adult females)

[43] BANGLADESH REFUGEE EMERGENCY Population Infographic (as of 18 March 2018) available at: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/62881

[45] Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, TOWARDS A PEACEFUL, FAIR AND PROSPEROUS FUTURE FOR THE PEOPLE OF RAKHINE Final Report of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State (August 2017) available at: http://www.kofiannanfoundation.org/app/uploads/2017/08/FinalReport_Eng.pdf

[46] Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, TOWARDS A PEACEFUL, FAIR AND PROSPEROUS FUTURE FOR THE PEOPLE OF RAKHINE Final Report of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State (August 2017) pg 20 available at: http://www.kofiannanfoundation.org/app/uploads/2017/08/FinalReport_Eng.pdf

[47] See for example, United News of Bangladesh, ‘Over 20 shops serving Rohingyas of Leda Camp gutted by fire’ (14 December 2017) available at: http://www.unb.com.bd/bangladesh-news/Over-20-shops-serving-Rohingyas-of-Leda-Camp-gutted-by-fire/58249

[48] Mohammad Mehedy Hassan, Audrey Culver Smith, Katherine Walker, Munshi Khaledur Rahman and Jane Southworth, Rohingya Refugee Crisis and Forest Cover Change in Teknaf, Bangladesh, MDPI Remote Sensing (2018) pg 16, available at: http://www.mdpi.com/2072-4292/10/5/689

[49] See: Reuters Graphics, ‘The Rohingya Crisis: Life in the camps‘ available at: http://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/rngs/MYANMAR-ROHINGYA/010051VB46G/index.html

[50] Xchange Foundation, Snapshot Survey: An Insight into the Daily Lives of the Rohingya in Unchiprang & Shamlapur (March 2018) available at: http://xchange.org/snapshot-survey/

[51] In a 2016 state-wide study, 52 percent of the respondents reported that they do not have access to adequate health care. See: Rakhine State Needs Assessment II, Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH), (January 2017) available at: http://www.cdnh.org/publication/rakhine-state-needs-assessment-ii/

[52] Medicins San Frontieres, ‘Myanmar/Bangladesh: Rohingya crisis – a summary of findings from six pooled surveys’ (9 December 2017) available at: https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/sites/usa/files/summary_of_findings_-_msf_mortality_surveys_-_coxs_bazar.pdf

[53] UNICEF, ‘OUTCAST AND DESPERATE: Rohingya refugee children face a perilous future’ (October 2017) available at: https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/UNICEF_Rohingya_refugee_children_2017.pdf

[54] Naw Betty Han, ‘Lack of knowledge about NVC card holding up repatriation: minister’ Myanmar Times (20 April 2018) https://www.mmtimes.com/news/lack-knowledge-about-nvc-card-holding-repatriation-minister.html