Investigating fatal childhood drowning incidents in the Cox’s Bazar refugee camps

Introduction

Drowning is a serious and neglected public health threat that results in the deaths of 320,000 people a year worldwide. Drowning is the second leading cause of childhood injury-related deaths worldwide and is the most common cause of injury-related deaths among under-fives. This issue is especially critical in Bangladesh, where drowning has previously been identified as the leading cause of death among children aged 1–17 years, with approximately 17,000 children drowning each year. Whilst there is not yet a national childhood drowning prevention scheme in Bangladesh, various studies and interventions have been undertaken throughout the country, particularly focusing on rural areas and children under 5 years old. However, such research and actions have so far largely neglected the refugee camps hosting Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar, a region where drowning is the fourth highest cause of accidental death, according to a UNDP district level report.

Drowning data collection since 2019 shows several incidents involving children under 5 years old drowning in unfenced water sources, such as ponds that are close to their shelters. In response, fences and barriers have been installed to restrict access and exposure to water bodies. However, there is also a need to consider interventions focusing on school age children who intentionally choose to enter the water to wash or play. Fatal drowning incidents involving children between the ages of 5 and 17 also occur in larger water bodies such as reservoirs and canals, often after the victims have finished or not attended school or madrasa.

Figure 1. Young boys playing in a lake in Kutupalong refugee camp, Cox’s Bazar.

In response to this, fatal drowning cases that occurred in the refugee camps in 2019 and 2020 have been investigated, to further explore the influencing factors and age groups associated with the drowning incidents and possible interventions. The field team was sent into the camps to speak to the families of children that have drowned in 2019 and 2020 and to examine the water bodies in which the incidents occurred.

Findings from the field

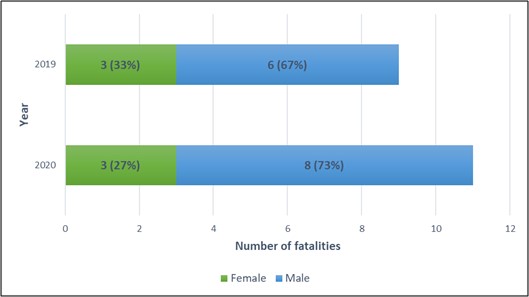

In total, eighteen fatal drowning incidents were recorded in 2019 and 2020, which resulted in the deaths of twenty children. The ages of the victims ranged from 2 to 17 years old. Fourteen (70%) of the victims were male and six (30%) were female. Six (30%) fatalities recorded were children under 5 and fourteen (70%) fatalities recorded were school age children (between 5 and 17 years old). Twelve (60%) of these fatalities occurred in ponds, three (15%) in canals, two (10%) in a deep man-made hole that had accumulated rain, and one (5%) each in a lake, reservoir and water bucket.

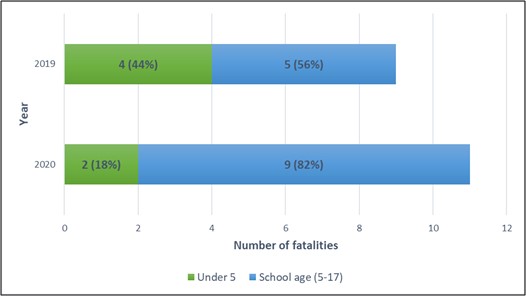

Nine fatalities were recorded in 2019. Four (44%) of the fatalities recorded in 2019 were children under the age of five. Each of these fatalities occurred as the victim’s parents were undertaking essential household activities, such as work, prayer and preparing food, which meant the child was unsupervised and wandered into ponds near their shelters. Five (56%) of the fatalities during 2019 were school age children. The majority of fatalities (67%) recorded in 2019 were boys (figure 2).

Eleven fatalities were recorded in 2020. Nine (82%) of the fatalities in 2020 were school age children. These occurred primarily in the afternoon, as the children went to play and bathe in canals, reservoirs and ponds without adult supervision, on days when there was no school or madrasa, or after finishing school or madrasa. Other common themes were; the fatalities occurring in water bodies described as far away from the victim’s home camp; victims engaging in behaviour such as bathing in ponds alone; and fatalities being witnessed by peers and bystanders who did not know how to help. In addition, three (27%) of the fatalities took place in a canal, after the children involved got into difficulty in the water. Two (18%) of the fatalities in 2020 were children under 5. Whilst one of these fatalities occurred in similar circumstances to those recorded in 2019, the other occurred as an unsupervised 2 years old child suffering from diarrhoea fell into a water bucket in her own shelter, as her mother briefly left her unsupervised. An important finding is that three (27%) of the fatalities that occurred in 2020 involved children that had epilepsy. Research from high-income countries shows that children with epilepsy are at a much higher risk of drowning. The majority of fatalities (73%) in 2020 were boys.

fatalities recorded in 2019 involved unsupervised children under 5 drowning in ponds close to their homes, and this finding supports previous research conducted in Bangladesh which highlighted the high drowning risks for children under 5 and emphasised the need for increased child supervision and fences to surround ponds. The fatalities recorded in 2020 revealed a shift in the age groups of the victims (figure 3). Whilst 2019 fatalities were almost evenly split between age categories, the 2020 findings data demonstrated an increase in school age child fatalities, and a decrease in fatalities to children under 5.

Figure 2. Age groups of fatalities recorded in 2019 and 2020.

The decrease in fatalities to children under 5 could be influenced by efforts undertaken in the last 18 months to build fences around ponds in the camps, which may have reduced the frequency of unsupervised children accidentally falling into the pools. The incidents involving school age child drownings may be influenced by several factors. Previous research has found that older children tend to be less closely supervised and more likely to engage in risky behaviour around water, whilst also drowning further from home, often 500 metres or more, where they swim alone or with peers who do not have swimming, rescue or resuscitation skills.

Figure 3. Sexes of fatalities recorded in 2019 and 2020.

The increase in drowning incidents involving this age group in 2020 may have also been partly influenced by the COVID-19 situation and related measures. 2020 saw a significant reduction in children attending schools and learning centres as a result of COVID-19 restrictions. Consequently, with limited or no school, children will have had more unstructured free time and would have been searching for activities and entertainment, and potentially increased the frequency of children playing and bathing in ponds, lakes, reservoirs and canals.

Conclusion and recommendations

This investigation has shown that childhood drowning is a grave issue in the refugee camps that requires urgent intervention. Drowning is preventable and there are proven strategies that can be implemented. However, different interventions are required for different age groups. For children under 5, the installation of fences and barriers and increased supervision are key measures that have been proven effective in Bangladesh. For older children, interventions may include teaching school age children basic water safety and safe rescue skills. This can also be complemented by training bystanders in safe rescue and resuscitation, strengthening public awareness of drowning and highlighting the vulnerability of children. These forms of intervention have already seen some success in other areas in Bangladesh through programmes such as SwimSafe, which teaches basic water safety and safe rescue skills to children age 7–17 years. Similar lifesaving training targeted at the children living in the refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar are highly needed.