“Life is a fight that should be fought”

Life in transit: Voices from returning migrants

Introduction

Though migration is intrinsic to Niger, movement through the country has been on the rise in recent years. Environmental, socio-economic, and political instability in the region have fueled an increase in northbound migration, particularly since the fall of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi in 2011. Increased insecurity in the region has made Niger a country of geostrategic importance in the trans-Saharan irregular migration corridor. In 2017, there were approximately 330,000 migrants on the move through Niger, with at least 100,000 migrants having passed through the country every year since 2000.

Diverse migratory routes from across West Africa have converged for centuries in Niger constituting mixed migration flows with varied motivations, strategies, and goals. Contrary to conventional belief, not all migrants travelling northwards through Niger have Europe in mind: 84% of migration happens internally within the ECOWAS region. However, most of those that do in fact reach Europe have at some point travelled through the country. In fact, three-quarters of all migrants of African origin that have arrived in Italy by boat in recent times have travelled through Niger.

Carpets. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Northbound migration flows have been used for centuries across West Africa for both human cargo and commerce, however, these routes are changing. The first part of the Niger Report 2019 expressed how such a shift in migration dynamics has come as a result of the Nigerien government’s crackdown on human smuggling, which de facto illegalized the centuries-old migration industry through the introduction of Law 2015-036. In addition to far-reaching consequences for the local population and economy, the migration industry has been driven underground; migrants, passeurs, and coxeurs have started to take non-traditional routes, crossing the north of Niger and into North Africa through longer and more perilous journeys. Departure locations and routes have changed to circumvent the big cities and lookouts have been posted in the desert to warn drivers about military patrols, as the region has become increasingly militarised since the crackdown started in 2015. West African migrants are now smuggled among Nigerien workers to avoid being detected, and police extortion and bribes at checkpoints are becoming increasingly common.

View from the Grand Mosque. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Migrants are crossing into Algeria in increasing numbers and in response to this influx, the Algerian military has started forcibly deporting migrants back into Niger, often done through questionable means as it has been reported that migrants are often dumped back in the desert at the Algerien border with Niger. Additionally, East Africans are increasingly travelling to Niger through Chad in order to avoid the dangers of transiting in Southern Libya. Of those making their way through Libya, many end up returning either due to the failure to reach Europe, or due to the abuses experienced in Libya at the hands of smugglers and authorities. Subsequently, Niger has become a temporary home to many of the returning migrants in the region as those returning from both Libya and Algeria end up in Niger; some will try their luck and travel north again, while others wait in Niger to return to their home countries or seek opportunities in another West African country. Of those wanting to go back to their countries of origin, many do so through IOM’s Assisted Voluntary Return (AVR) program, and as a consequence will stay in Niger’s ‘transit centres’ for extended periods of time.

Our Central Mediterranean Survey sought to understand the experiences of migrants who were making their way to Europe. This time, Xchange Foundation has investigated what happens to those who either did not plan to cross the Mediterranean in the first place or did not manage to do so successfully. Seeking to understand the experiences of these returning migrants, Xchange was in Niger to carry out field research. As the first part of the Niger Report 2019 expressed, Agadez is one of the biggest migration hubs for Sub-Saharan Africans travelling northwards, towards Libya and Algeria, or southwards. During its one-month mission in Agadez, Xchange Foundation collected first-hand data and testimonies from migrants transiting through Niger in mixed migration flows across Africa. These qualitative data considered the complex routes being taken by migrants, the abuse and human rights violations they experienced since leaving their homes, as well as their intended destinations and expectations from their outward travels. The research project involved returning migrants (via Assisted Voluntary Return (AVR) and personal volition), expelled migrants from neighbouring countries (Algeria and Libya), and recipients of UNHCR’s Emergency Transit Mechanism (EMT) arriving in Niger from Libya.

This part of the report aims to do the following:

- Map current and recent shifts in migratory routes across Africa through Niger (including outflows, inflows, and circular migration);

- Identify human rights abuses experienced by migrants on these routes and the perpetrators of these abuses;

- Identify migrants' original destination country, their expectations for the route, as well as future steps on their journeys.

Methodology & Research Implementation

Fieldwork-Data Collection

In late 2018, Xchange conducted fieldwork to obtain first-hand data from migrants transiting Niger. The cross-sectional survey informing this report took place in Agadez, Niger, between November 5 and December 4, 2018. The data were collected using a purposive sampling technique, where only ‘returning’ migrants were targeted and sampled. This research combined quantitative and qualitative methodologies to primarily identify:

- Contemporary migratory routes across Africa and;

- Incidents experienced by migrants on the move.

The population of migrants transiting Agadez fluctuates and cannot be exactly determined, as, according to local authorities, there is “no official mechanism collecting accurate data”. No sample can therefore be considered representative of all migration movements through Agadez. However, Xchange aimed to include a diverse group of respondents to capture a broad picture of the migratory routes and a variety of potentially experienced or witnessed events or incidents, reaching a sample size of 189 migrants.

In this report, there was no specification applied with regards to the interviewees' immigration status; the term 'migrant' is used throughout the whole report to refer to all respondents (e.g. refugees, asylum seekers, economic migrants). Here, a 'returning migrant', or 'returnee', is defined as any African migrant who had reached either Libya or Algeria, and who – irrespective of whether their intention was to continue travelling outside of the African continent – ended up in Agadez.

Data Collection. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Three days prior to the official data collection period, the research team conducted a pilot test of the research instrument in both French and English. Minor changes were made to the questionnaire to facilitate the respondents’ understanding and reduce any potential response bias.

The data collection team consisted of two enumerators, one male and one female, both Nigeriens, and fluent in local languages, French, and English. The enumerators administered questionnaires in English or French, depending on which language the respondents felt more comfortable conversing in, with the use of a mobile application which allowed the data to be collected offline. At the end of each collection day, the surveys were immediately uploaded to an online platform for review by the coordinator thereby minimizing data loss.

Whenever required, interpreters - who were migrants themselves - were used to facilitate interviews. For instance, in the Sudanese community, two migrants who spoke good English assisted the enumerators on the spot with those respondents who only spoke Arabic. In detail, 115 surveys were conducted in French, 30 in English, 28 in Arabic, 14 in Hausa, and two in Zarma. The majority of the interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes.

The research instrument included closed-ended (yes/no), open-ended, and multiple-choice questions. In the final section of the survey, respondents were given the option to share any experiences or opinions they deemed relevant to the survey. The questionnaire included questions regarding the migrants' demographic profiles, push or pull factors, types of journeys and routes, countries and locations transited, time and cost of travel, most significant incidents experienced or witnessed since departing from their home countries, as well as plans for the near future.

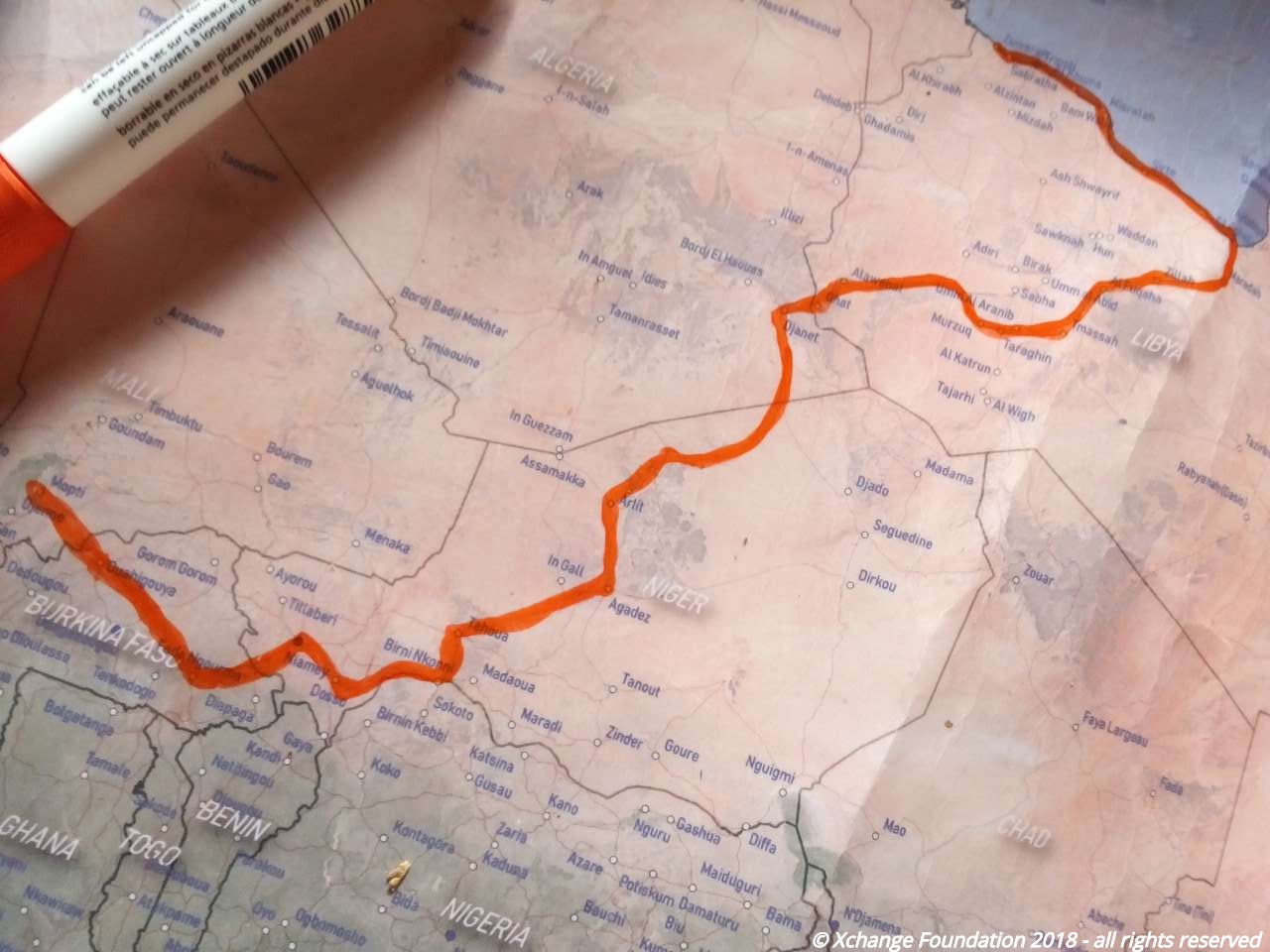

During each interview, every respondent was provided with a detailed map of Africa to identify the transit hubs and draw with a marker the route they took since they left their home countries. This allowed the researchers to subsequently reconstruct the respondent’s routes in the most accurate way possible.

Data Collection: map of outward journey of a Malian migrant. - © Xchange.org 2018

Ethical Considerations

The purpose and objectives of the project were explained to all respondents prior to any data being collected. Moreover, all respondents were provided with anonymity and the right to withdraw from the study at any time. Verbal consent was ensured right before proceeding with the surveys. The interviews were generally done in public spaces where the migrants felt comfortable talking and, at times, in a separated area to ensure their privacy was protected and their dignity preserved. All female respondents were interviewed by the female enumerator to establish a high level of rapport between interviewer and interviewees, and to ensure the information received was as unbiased as possible.

As participation in the project was done entirely on a voluntary basis, none of the respondents were promised any compensation prior to the survey. However, after the completion of several interviews, the enumerators made sure that some migrants were rewarded in-kind, depending on their needs (medicine, rice, sugar, tea) as a show of appreciation for their time. No respondents were rewarded financially.

Interview with a West African returnee. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Limitations

Overall, there were several limitations associated with the data collection, which initially was intended to last two weeks and reach a sample of 200 returning migrants. Technical problems with the data collection application, the length of the questionnaire, and the unavailability of migrants to take part in the survey were some of the limitations experienced. As a result, fewer interviews (189) were conducted, some of which were incomplete due to unintended data loss.

Many potential respondents did not agree to be interviewed as they were either afraid to share their stories or had become “tired of all the ‘research’ and ‘assessments’ going on in Agadez”. Others demanded to be paid for their time instead of providing information voluntarily. This phenomenon consequently limited opportunities for data collection. The interviewed migrants, however, were more than happy to participate in the project, openly sharing their feelings at the end of interviews:

Burkinabe female [02]

Disruptions in data collection were quite prevalent. On occasion, the data collection application would encounter technical problems leading to some answers not being recorded. This reduced the sample size for certain variables during the analysis. The retrospective character of the research understandably resulted in missing data, as respondents oftentimes could not remember exact dates of events or all the cities they transited through during their journeys. To ensure high-quality data and analysis for the report, some respondents’ responses were not included in the analysis as the data collected was not sufficient to reconstruct the complete itinerary of their journey.

It must be noted that the frequency of occurrence of human rights violations is most likely higher than presented in this report. According to the enumerators, respondents did not report all the incidents they had either experienced or witnessed for several reasons. These included being physically or mentally tired while the survey was taking place. Hence, for practical reasons and to ensure quality data, the interviewers asked about particular incidents - not all incidents - allowing the migrants to primarily focus on those events they thought were most important/relevant.

Challenges in validity and reliability were moderated by employing extensively trained enumerators, conducting daily analysis of the uploaded surveys, holding meetings to discuss the status of data collection and solving any difficulties that had arisen during the process. The fact that the enumerators were Africans themselves, assisted significantly in Xchange gaining the trust of respondents, minimising bias, and filling in cultural gaps where needed. However, on several occasions the enumerators used migrants as interpreters which increased the length of the interviews and might have also influenced the level of detail and accuracy of the testimonies. As a result, it was considered appropriate that a few surveys be discontinued and completed the following day, as their length prevented some respondents from participating fully.

Returning Migrant Profiles

Sex and Age

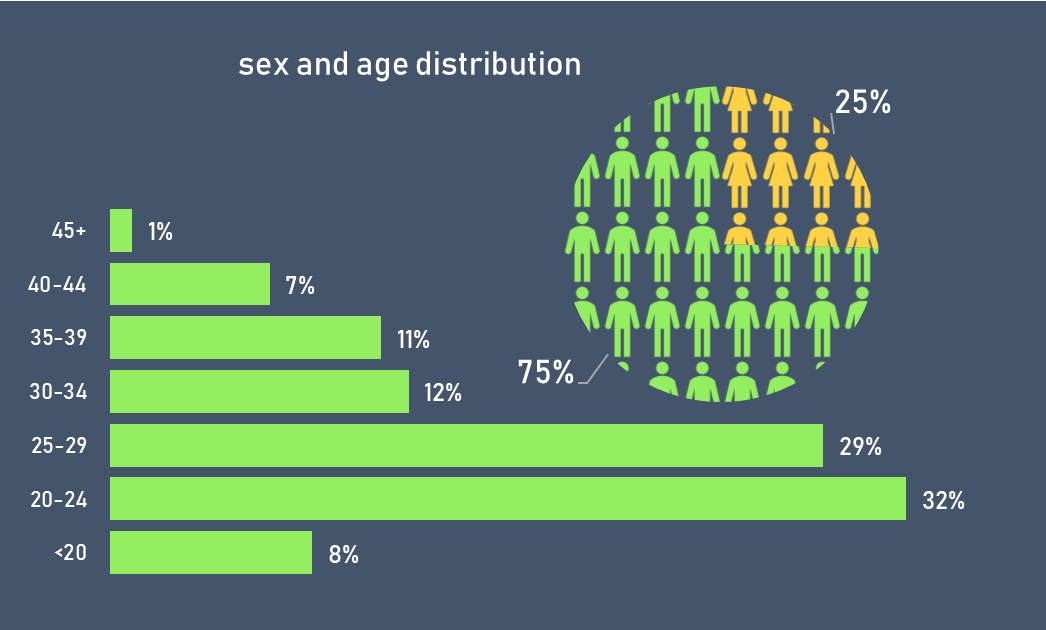

Sex and Age distribution of the sample - © Xchange.org 2019

The sample comprised of a total of 189 returning migrants, all of which were at the time residing in Agadez. One in four respondents (48) were female and three in four (141) were male. This sex imbalance is partly due to the fact that fewer females typically attempt the journey, making in turn more males available for interview. The proportion of females included in the survey can be considered quite high in comparison to the total number of migrants transiting through Niger.

The respondents’ ages ranged from 18 to 52 years. Overall, respondents were quite young, with 69% (125) being below the age of 30 at the time of enumeration. Disaggregated by sex, relatively more males than females were below the age of 30; eight in ten males (79%) compared to four in ten (39%) females. The largest age groups surveyed were 20 to 24-year-olds (58 respondents) and 25 to 29-year-olds (52 respondents).

National and Ethnic origin

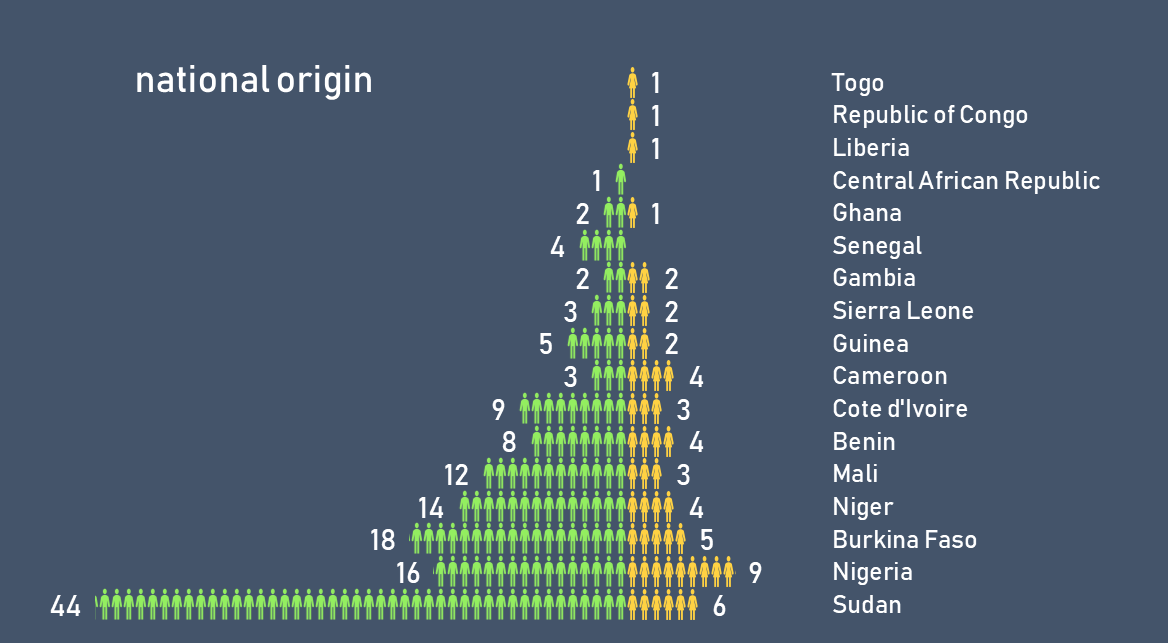

Pyramid of national origin of respondents - © Xchange.org 2019

The sample on national origin was quite diverse, with respondents originating from 17 countries in the African continent. Overall, female respondents came from 15 countries, while male respondents came from 14 countries.

A majority of our respondents were Sudanese (26%), representing the large community of Sudanese asylum seekers in Agadez. The remaining nationalities included Nigerians (13%), Burkinabes (12%), Nigeriens (10%), Malians (8%), Beninese (6%), and Ivorians (6%). There was also one female respondent from each of the following countries: Togo, Republic of Congo, Liberia, as well as one male from the Central African Republic. All the interviewed Senegalese were males.

Interractive map of respondents' origins - © Xchange.org 2019

Respondents originated from 94 different cities and villages within these 17 countries of origin. The cities represented by the highest number of respondents were Niyala and Al-Fashir in Sudan (14 and 13 respondents, respectively), Zinder in Niger (nine), Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso (eight), Djougou in Benin (seven), Benin City in Nigeria, Bobo Dioulasso in Burkina Faso, Gao in Mali (each five), and Bouake in Ivory Coast (four). Apart from the eight from Ouagadougou, 15 more respondents originated from the capitals of their respective 11 countries of origin: one from Monrovia, Brazzaville, Conakry, Freetown, Banjul, Bangui, Niamey; two from Yamoussoukro; and three from Bamako.

Moreover, the interviewed migrants reported over 40 different ethnic identities in total, with 18% identifying as Zaghawa, 16% as Fula/Fulani/Peuls, 14% as Hausa, 4% as Igbo-Ibo and Fon, 3% as Mossi and Yoruba/Itsekiri. In detail, the majority of Sudanese (64%) were Zaghawa; 32% of Nigerians were Hausa and 32% Igbo/Ibo; 29% of Burkinabes were Fula, 24% Mossi, and 19% Bobo; 72% of Nigeriens were Hausa; 33% of Malians were Songhai, and 27% Tuareg; and 55% of the Beninese were Fon.

Traditional (Fulani) Hat. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Respondents were also asked to state how many and which languages they felt comfortable speaking. Overall, there were 47 distinct languages stated by the 189 respondents, ranging from one to seven languages spoken per respondent, with a median of 2 languages spoken per respondent. 51% (96 respondents) were French-speaking, 34% (65) Arabic, while English came as the third most-spoken language with 27% (51).

Education and profession in country of origin

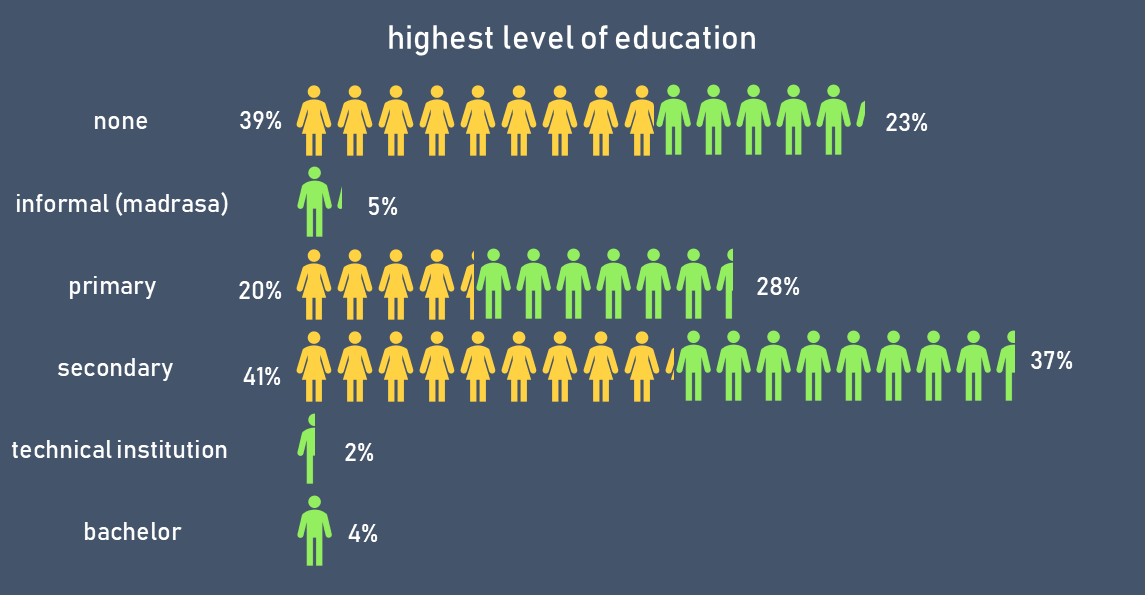

Highest level of education of respondents - © Xchange.org 2019

Overall, 38% of the sample (69) had secondary education and 26% (47) had primary. A substantial 27% (49 respondents) were not educated at the time of the study, while seven respondents (5%) had attended only informal (religious) education in madrasas. Two in five (18, or 39%) females had not attended any form of education while two in five (19, or 41%) had completed secondary education. In comparison, 37% of males (50) had secondary education and 23% (31) had none. None of the females went to university compared to 4% of males (6), who were holders of a bachelor's degree.

One in five (34, or 19%) respondents reported they gained no skills in their home country. 49 respondents (27%) worked in agriculture, 41 respondents (23%) in trade (half of the females were in trade), 15 respondents (8%) in transportation, and 11 respondents (6%) in construction.

Prayer. Agadez Market - © Xchange.org 2018

Religious Identity, Marital Status, and Disability

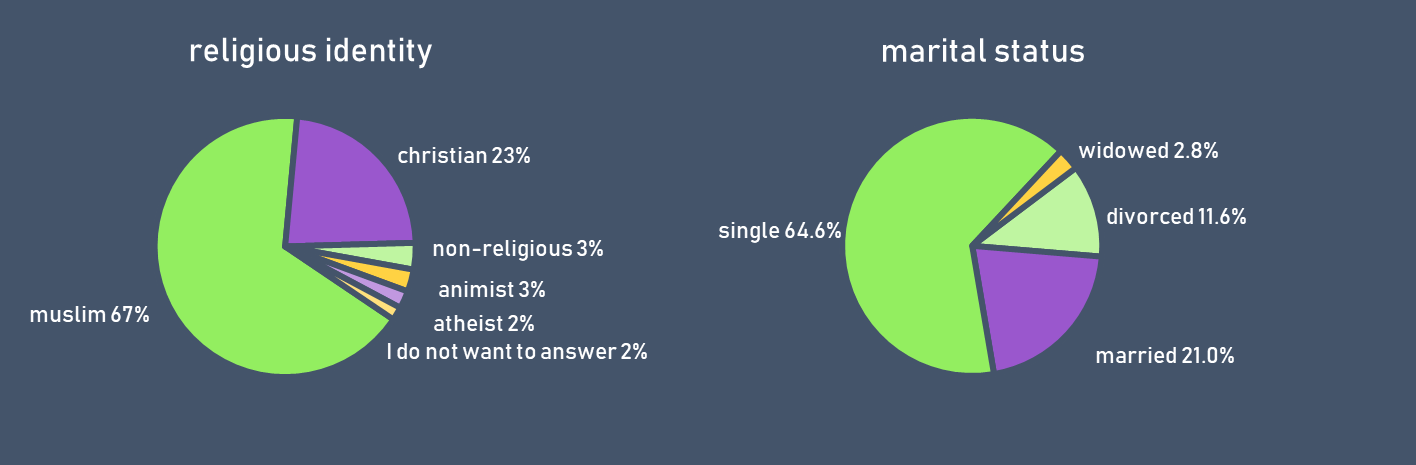

Religion and Marital Status of respondents - © Xchange.org 2019

The majority of the sample (67%, or 122) identified as Muslim, 77% of whom identified as Sunni, and 16% as ‘just Muslim’ without specifying any affiliation. Christians represented the second-largest group with 42 respondents (23%) belonging to one of Christianity’s subdivisions; 48% Catholics, 36% Protestants, and 7% Orthodox. Six individuals were animists, five non-religious, three Jehovah’s witnesses, and three atheists, while a 2.2% did not wish to disclose a religious affiliation.

With regards to their marital status at the time the survey took place, 65% of the sample (117) reported being single, 21% (38) were married, 12% (21) were divorced and 3% (5) were widowed. Relatively more males (72%) were single compared to females (44%), while one in four females (26%) had gotten divorced compared to only a few (7%) males.

Only six individuals reported having some sort of disability (physical or mental), while the vast majority (97%) reported being healthy.

Sudanese male [17]

However, the real percentage of those reporting a disability should have been higher, as it was reported by the enumerators that interviewees had different understandings of what a disability entailed and many hesitated to answer the question.

Market. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Leaving the country of origin

Push and pull factors

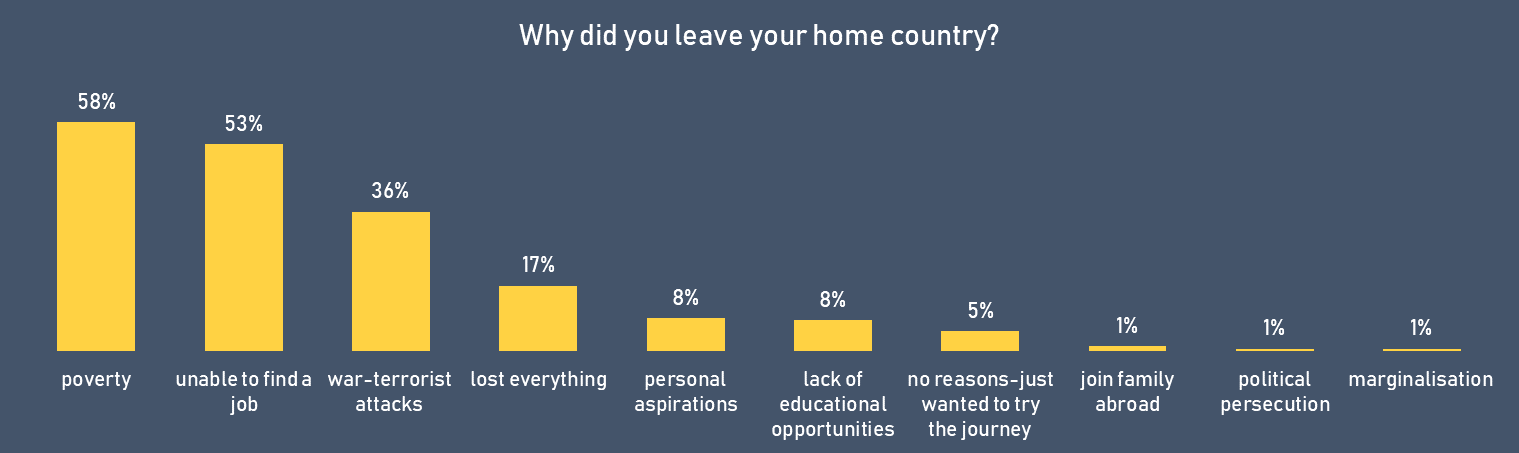

Leaving the country of origin: Push and Pull factors - © Xchange.org 2019

Most respondents left their countries of origin to escape poverty, war, and terrorist attacks, as well as due to a lack of employment and educational opportunities. 15 respondents (8%) left to realise their dreams, e.g. become a football player. There were only a few individuals (9, or 5%) who “just wanted to try the journey”.

Encouragement and advice before the journey

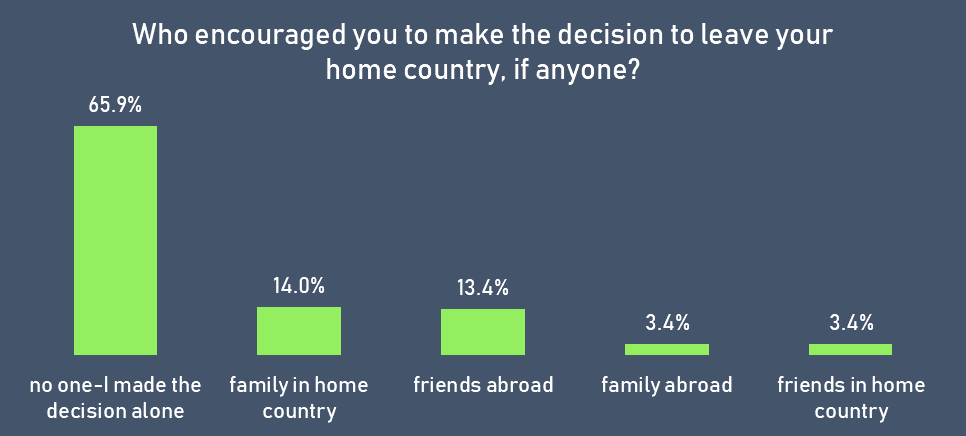

Encouragement to leave - © Xchange.org 2019

We asked the respondents whether they had made the decision to leave their country of origin. Two in three migrants (118, or 66% of the sample) indicated leaving was an autonomous decision. The remaining 34% (61) were encouraged by; family in their home country (14%), friends abroad (13%), family abroad (3%), or friends in their home country (3%). By sex, 70% of male migrants made the decision to leave alone compared to 54% of females. Also, 13% of males were encouraged by their family and 24% of females were encouraged by friends who had already migrated and had been living abroad at that time.

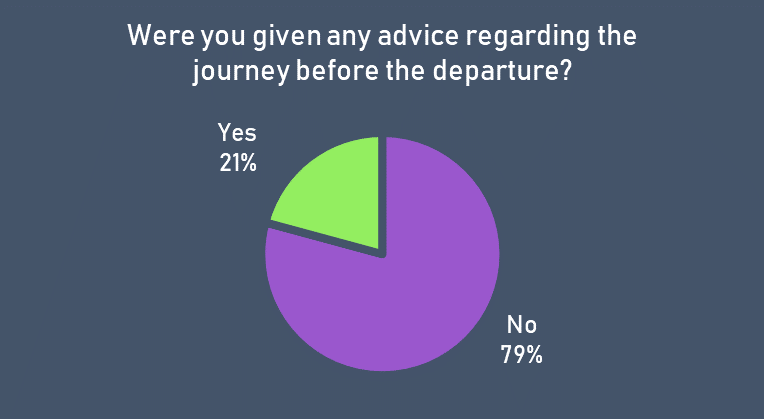

Advice before departure - © Xchange.org 2019

The vast majority (141, or 79%) replied in the negative as to whether they had received any advice before leaving their home country regarding what they should have been aware of during their journey. Relatively fewer females (15%) said they were advised by someone they trusted in comparison to males (23%). Those who were counselled by someone before leaving reported being given mostly general advice along the lines of “taking care of oneself”. Almost all evaluated this advice as ‘very valuable’.

Sudanese female [04]

Gambian male [02]

Nigerien male [04]

However, only a few were given specific advice with regards to practicalities, incidents that might occur, or how to avoid certain difficult situations.

Malian male [06]

Intended country of destination

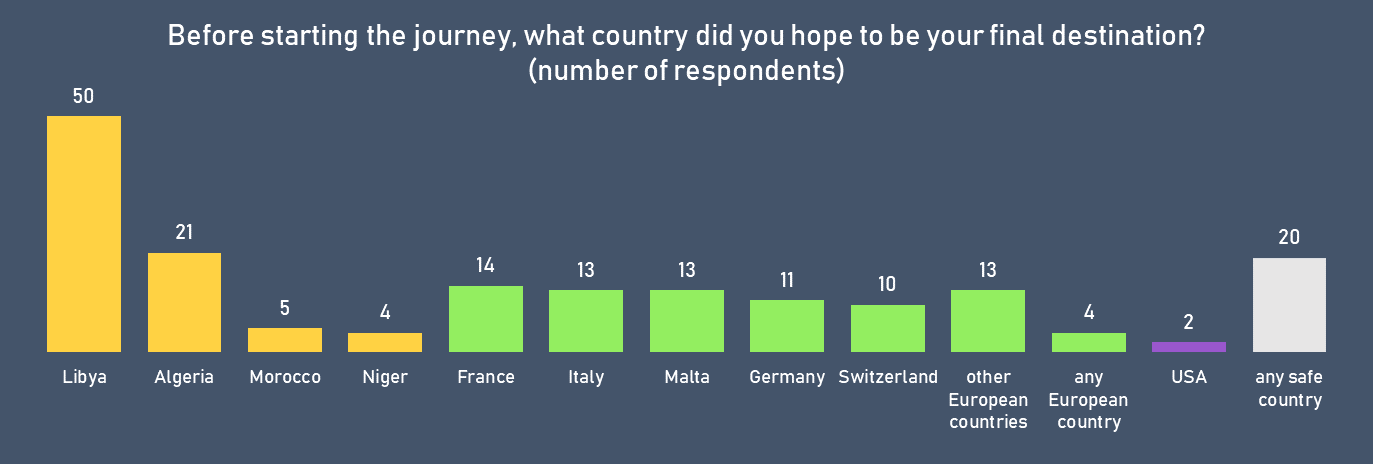

Intended destination countries - © Xchange.org 2019

The majority of migrants who returned to Niger did not intend to go to Europe in the first place - a finding that is supported later in this report. 44.4% (80) of the interviewed migrants intended to go to an African country (in order: Libya, Algeria, Morocco, Niger) with the goal of finding a job.

Guinean male [03]

Nigerien female [03]

Sudanese respondents left for Libya aspiring to begin a new life, but their expectations were shattered once they arrived.

Sudanese male [15]

Some Nigerians decided to leave due to the insecurity caused by Boko Haram in northern Nigeria and headed to Niger because they heard about IOM’s presence there. However, their plans must have changed while in Niger, as they continued north towards Libya.

Nigerian male [16]

Grand Mosque of Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

On the other hand, 43.3% (78) aspired to cross the Mediterranean and go to Europe (11 countries with most-mentioned being France, Italy, Malta, Germany, and Switzerland), 11.1% (20) would consider moving anywhere in the world where they felt safe, whereas 1.1% wanted to go to the USA. The most-reported statements of those considering going to Europe included: “to earn a lot of money”, “to better my life”, “to earn a living”, and “to marry a European”. Their decisions were based partly on word of mouth; what they heard from other migrants they know, such as family members or friends abroad, and partly on the opinions they formed based on the media’s portrayal of European countries and ‘success stories’ of other migrants.

Malian male [11]

Nigerian male [09]

Burkinabe male [11]

Burkinabe female [02]

Malian male [01]

Malian male [02]

Liberian female

Nigerian female [07]

All those who aspired to reach any safe country were from either Sudan or the Central African Republic.

Central African male

Identification documents

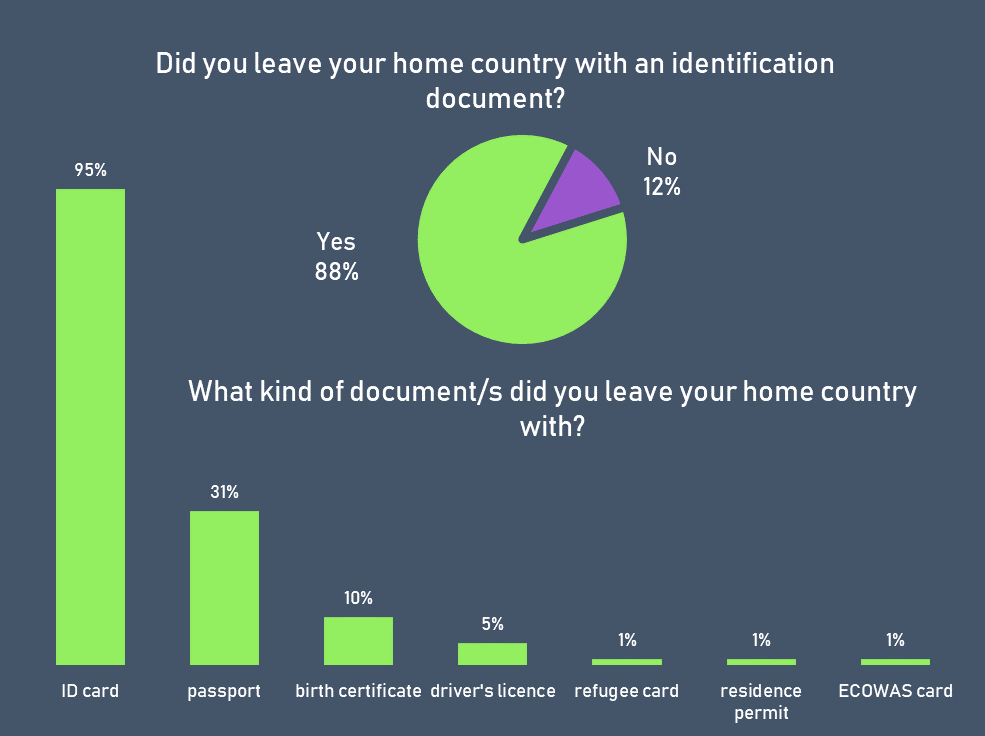

Possession of identification documents at departure - © Xchange.org 2019

88% (156 respondents) left their home country with some sort of identification document in their possession. 12% (22) left without any form of identification, most of whom were Sudanese; three in ten (30%) of those leaving Sudan did not have an identification document, compared to relatively lower proportions coming from other countries. Of those who left with at least one identification document, 95% had a national ID card, 30% had a passport, and 10% had a birth certificate.

'Boutique'. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Outward Journey

Overall, the collected spatial data allowed for the mapping of a total of 185 migrant journeys (out of the 189 total conducted surveys). The outward routes were categorised based on the region of Africa respondents departed from, and the analysis of their routes was done according to this categorisation: Burkina Faso-Mali: 38; Niger: 18; Nigeria-Cameroon: 33; Sudan-Chad-Central African Republic: 51; West African Coast (comprised of those departing from Senegal, The Gambia, Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire, Benin, Togo): 45.

Not all respondents departed from their city or even country of origin. In particular, 22% departed from another city within their country of origin. Relatively more females were found to depart from another city (47% compared to 14% of males). A few (3%) departed from a country other than their country of origin.

78% (144) of respondents departed for their outward journey between 2015 and 2018; most migrants departed during the first half of 2016 (31), the first half of 2017 (27) and the second half of 2016 (26). 22% of the sample had departed before 2015, hence before the implementation of Law 2015-036. On average, the outward journey lasted 29 months for the respondents (a median time of two whole years).

Outward journey routes

Map showing all outward routes used by the respondents.- ©️ Xchange.org 2019

Burkina Faso-Mali

Map showing the routes followed by migrants who departed from Burkina Faso and Mali - © Xchange.org 2019

23 respondents departed from Burkina Faso, a majority of whom (eight) from the capital city, Ouagadougou. Most Burkinabe respondents followed the regular Banfora to Niamey route, via Bobo Dioulasso, Ouagadougou, Fada Ngourma, and Kanchari, some incorporating Tenkodogo and/or Diapaga to their itineraries. Three of the 18 respondents did not follow the above-mentioned route but headed north towards Mali, crossing into Algeria via Gao and Aguelhok.

The 15 respondents who left Mali followed similar itineraries to the Burkinabes, most crossing straight into Algeria from the southwest of the country. Three respondents transited Niger, either via Burkina Faso or from Gao to Ayorou in southwest Niger. Only a few respondents departing from Mali entered Libya, with those who did so crossing in from Algeria. The majority of Malians crossed the Mali-Algeria border at Borj Badji Mokhtar or Timiaouine, heading towards Reggane or In Amguel respectively. One respondent diverted from these common routes, entering Algeria from the southwest after transiting Araouane and Taoudenni.

Typically, those migrants who cross into Libya from Algeria do so from either Djanet or Debdeb to Ghat or Ghadamis respectively. However, there was one respondent from Burkina Faso who entered Libya directly from I-n-Amenas to Dirj. Of those who transited Niger, there were two migrants who reported circumventing Assamakka and from Arlit headed to Djanet without stopping in between.

Niger

Map showing the routes followed by migrants who departed from Niger - © Xchange.org 2019

Ten of the 18 Nigerien respondents departed from Zinder, a city in the south of Niger known for its high rate of outmigration towards Algeria and Libya. All respondents transited Agadez on their way to either Libya or Algeria and followed the regular Dirkou-Séguedine-Madama and Arlit-Assamakka routes respectively. Just two respondents diverted from these routes; one circumventing Assamakka on their way to Algeria, and one transiting Djado on their way to Madama from Séguedine.

An interesting observation on the route to Libya, however, is that two respondents did not follow the Madama-Al Wigh way, but entered Libya from the southwest, close to the Niger-Libya-Algeria border heading directly to Ghat in Libya.

The routes Nigerien migrants took within Libya and Algeria were much shorter in distance than those taken by other migrants. Moreover, unlike other respondents, none of the interviewed Nigerien migrants passed through both Algeria and Libya during their outward journeys, possibly indicating that they had a clear destination in mind before departing Niger.

Nigeria-Cameroon

Map showing the routes followed by migrants who departed from Nigeria and Cameroon - © Xchange.org 2019

The Nigerian and Congolese respondents departed from all across Nigeria; five from Bauchi, five from Benin City, and four from Abuja. The majority of those departing from the south of the country headed northwards and entered Niger from the south via Abuja and Kano. One respondent travelled through Benin, while two transited Chad and headed to the northeast of Libya via Al Jawf in Al Kufra.

The seven respondents from Cameroon entered Nigeria and took routes similar to the Nigerian itineraries; two via Benin, others transiting Kano and from Zinder towards Libya, while one went from Maiduguri to Diffa in Niger and from there headed north towards Madama, and from there into Libya.

Perhaps the most interesting finding is that several respondents departing from Nigeria and Cameroon did not transit Assamakka at the Niger-Algeria border, which is the main entry point into Algeria from Niger. Instead, after reaching Arlit (north of Agadez) they took an alternative route towards Djanet in southeast Algeria via the Air Mountains, a route not previously recorded in our Central Mediterranean Survey. Moreover, from Djanet, four respondents crossed into Libya from the southwest, transiting Ghat and Alawenat on their way north.

West African Coast

Map showing the routes followed by migrants who departed from countries in the West African coast - © Xchange.org 2019

Overall, migrants departing from countries of the West African Coast (comprised of Senegal, The Gambia, Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Benin, and Togo) followed a combination of all the above-mentioned itineraries. Typically, the 45 migrants who departed from these countries transited Burkina Faso, Niger, and/or Mali before entering Libya or Algeria; 39 transited Niger, 19 transited Burkina Faso, 19 transited Mali, 33 transited Algeria, and 29 transited Libya. All migrants departing from Benin crossed into Niger via Kandi to Gaya in Niger. One Ivorian respondent reported reaching Tangier in Morocco and after failing to cross the Strait of Gibraltar, headed back to Algeria.

Regarding ‘irregular’ border crossings, one Guinean respondent went directly from Gao, Mali to Arlit, Niger and from Arlit to Tamanrasset, Algeria, avoiding transiting Assamakka and In Guezzam. Another Guinean entered Libya directly from I-n-Amenas to Dirj. Six respondents, all departing from different countries went from Arlit to Djanet circumventing Assamakka, In Guezzam, and Tamanrasset.

Sudan-Chad-Central African Republic

Map showing the routes followed by migrants who departed from Sudan, Chad, and the Central African Republic - © Xchange.org 2019

All 51 respondents departing from Sudan, Chad, and CAR headed towards Libya in a bid to escape war and poverty in search of a better future. The majority of Sudanese departed from war-torn Darfur in the south of the country, mostly from Niyala and Al-Fashir. Two respondents departed from Chad, where they had relocated earlier in their lives as refugees.

Eight respondents departing from Darfur headed north, and entered directly into Libya via the Al Kufra region, heading to Al Jawf, Rabyanah (oasis), or directly to Qatrun. One transited Egypt and entered Libya from Al Jaghbub in the North-East of the country.

The majority of respondents taking this route (42), however, transited Chad (Zouar, Faya-Largeau, Fada) before entering Libya. Of those who crossed Chad, two respondents entered Niger from the east, one from Mao, central Chad, to Nguigmi, Niger, and one from Zouar, north of Chad, to Dirkou, Niger, and continued to Libya via Madama. The Central African left the capital of his country, Bangui, and headed towards Sudan, from where he continued in a similar way as the majority of the Sudanese.

Two in three respondents (34) taking this route transited Qatrun, which was the first reported stop in Libya for most. Many of the respondents never reached the coastal cities of Libya, either because they did not attempt to or because they did not have the means.

Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Agadez as a transit hub

For the majority of the interviewed migrants, it was at least their second time being in Agadez. 107 out of 185 (58%) migrants had transited Agadez before reaching Libya or Algeria. Moreover, the fact that none of the Sudanese migrants transited Agadez before reaching Libya means that 107 out of 136 (79%) migrants leaving all other countries of departure transited Agadez before arriving in Libya or Algeria.

From the 102 respondents (excluding the Sudanese) who departed for their journey between 2015 and 2018, 82 (80%) passed through Agadez, making it the most transited city before the Libyan and Algerian borders as reported by respondents. This corroborates the findings of our Central Mediterranean Survey and Niger Report 2019 (Part One) that Agadez is still a major transit hub despite Law 2015-036, which attempted to stall Sub-Saharan African migration in Niger.

Adedeta. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Modes of transport - Passeurs, coxeurs, and drivers

On average, each migrant used at least two modes of transport to get to the furthest point of their journey before they either made the decision or were forced to start heading south towards Agadez. The most-used means of transport reported were: car by 128 respondents (74%); bus by 127 respondents (73%); SUV by 94 respondents (54%); and truck by 31 respondents (18%). Moreover, a few reported walking long distances, while two migrants mentioned riding a camel to traverse some part of the Sahara. No respondents flew by plane during their outward journey.

Respondents were asked how many passeurs, coxeurs, and drivers were used to reach the furthermost point of their journey (in Libya or Algeria) from their country of departure. On average, each migrant used five or six different passeurs, coxeurs, and drivers. 21 migrants reported using more than ten different passeurs, coxeurs, and drivers. By geographical area of departure, as expected, the further away from Libya and Algeria the more passeurs, coxeurs, and drivers migrants used; those departing from Sudan-Chad-CAR and Niger used fewer than four passeurs, coxeurs, and drivers (73% and 61%, respectively). Those departing from the other regions used more on average.

With regards to the nationalities of these passeurs, coxeurs, and drivers, 99 (56%) respondents remember at least one of them being Nigerien, 77 (43%) at least one Malian, 55 (30%) at least one Libyan, 51 (29%) at least one Algerian, while the majority of those departing from Sudan-Chad-CAR (57%) and Nigeria-Cameroon (78%) reported being transported by people from Sudan and Nigeria respectively. All Nigeriens used at least one Nigerien passeur, coxeur, or driver. 76% of respondents departing from West African Coastal countries used at least one Nigerien passeur, coxeur, or driver.

Agadez market - © Xchange.org 2018

Income-earning activities during the journey

87% (155 respondents) stated that they worked at least one job during their journey, with the most frequently mentioned locations being Sabha, Qatrun, and Tripoli in Libya, and Tamanrasset and Algiers in Algeria. Many said they worked wherever they could, with several considering begging in the streets as work. Most interviewees identified markets, houses of wealthy individuals, restaurants, buildings under construction, as well as ghettos as their work environments. Men primarily worked in cleaning, guarding, selling products, and farming, whereas a few women were involved in domestic work.

Beninese female [01]

More than half of the female migrants (21) who worked during their journey, however, said their main income-earning activity was prostitution.

Togolese female

Cameroonian female [04]

Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Many males described the working conditions as being extremely bad, and on numerous occasions reported not being paid at all.

Sudanese male [42]

Malian male [01]

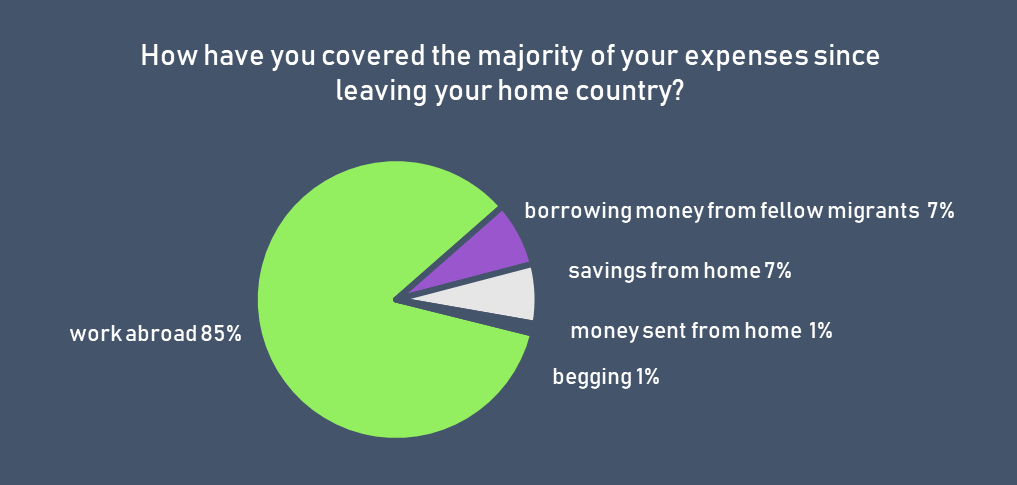

Covering the majority of expenses during the journey - © Xchange.org 2019

The vast majority (85%) reported that most of their expenses were covered by the income-earning activities they practiced abroad (including begging and prostitution), while savings from home (7%) and borrowing money from other migrants (7%) covered the majority of a few migrants’ expenses.

Ivorian female [01]

When asked in what currencies they paid smugglers throughout their journeys, the majority (71%) mentioned to have used the West African Franc (XOF), followed by 53% paying in Libyan Dinars and 29% in Algerian Dinars. Those departing from Nigeria or Cameroon paid in Nigerian Naira, and those departing or transiting Sudan paid in Sudanese Pounds. Four individuals paid in Euros and one in USD.

Attempt to cross the Mediterranean Sea

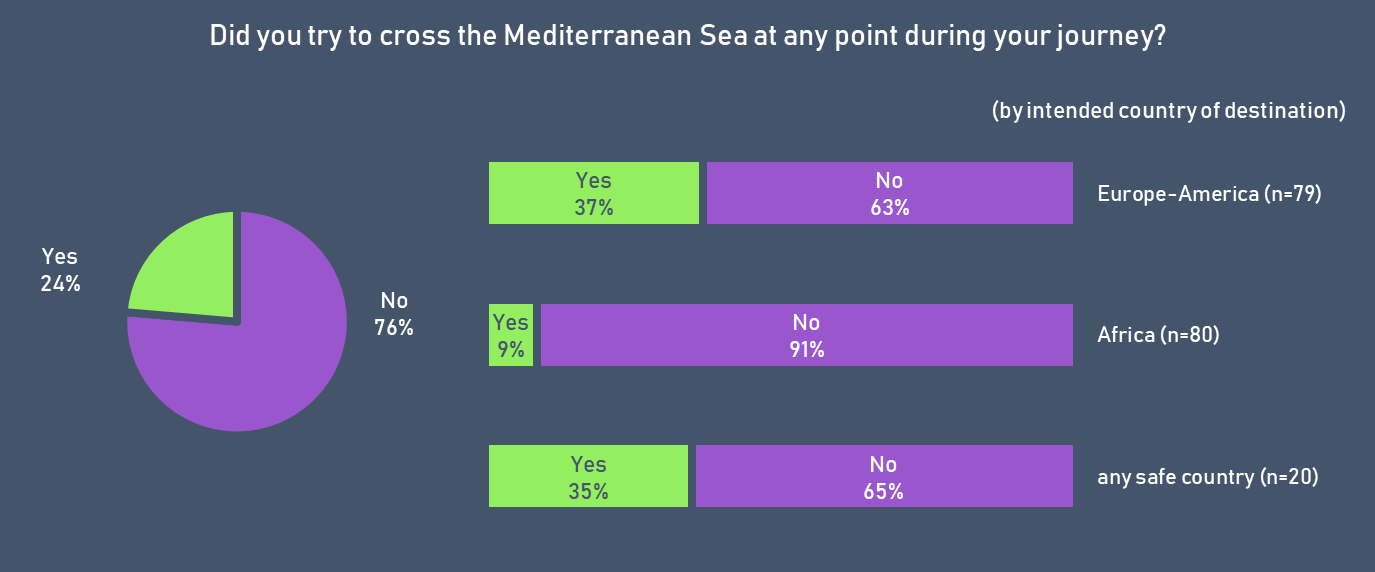

Attempt to cross the Mediterranean Sea - © Xchange.org 2019

One in four (24%) migrants interviewed had attempted to cross the Mediterranean from Libya, Algeria, or Morocco and failed. By sex, relatively more females (35%) than males (20%) attempted the crossing at least once. None of the respondents coming from the Central African Republic, Ghana, Guinea, Niger, Republic of Congo, Senegal and Togo tried to do the crossing.

The remaining 76% did not attempt to cross the Mediterranean. Interestingly, many of those who previously reported intending to go to Europe before they departed for their outward journey, did not attempt to cross the Mediterranean. This might imply that either they did not have enough savings, were detained, or never managed to reach the Libyan or Algerian shores - among other explanations. However, what is more interesting is that several people who did not intend to continue their journey outside the African continent when they first started did eventually attempt to cross the Mediterranean, possibly tempted by others.

Those 44 migrants who tried to cross the Mediterranean Sea, did so in their majority (89%) from Libya (11 from Tripoli, six from Sabratha, six from Misratah, four from Sirte). 43% tried only once, while there were more who failed between two and seven times (55%).

Burkinabe male [11]

Burkinabe female [03]

Gambian male [02]

Sudanese male [09]

Some reported that they were given away to police despite being compliant and paying the exact amount asked by coxeurs and passeurs.

Cameroonian female [04]

Burkinabe female [04]

Desert. Agadez Region - © Xchange.org 2018

Starvation and Dehydration

During their journeys, respondents also faced harsh travelling conditions; many suffered medical complications from dehydration, exhaustion, and lack of food. 73 respondents (39%) reported starving from the lack of available food to them at some point during their outward journey. One in five (22%) experienced dehydration.

Sudanese male [18]

Malian male [12]

Incidents during outward journey

Irrespective of the respondents’ identities, routes taken, or the duration of the journeys, interviewees faced violence and exploitation throughout their outward journeys at the hands of smugglers, government officials, gangs, insurgent groups, and abusive citizens.

The types of incidents that this study collected data on were extortion-bribery, discrimination (marginalisation), robbery, physical abuse, sexual harassment and abuse, detention, slavery-bonded labour, torture, abandonment in the desert, and death. Overall, relatively more females reported incidents of human rights violations than males. A significant number of respondents avoided sharing their experiences, either stating that they are not mentally prepared to remember what happened to them, or that they had more stories to tell than the interview would cover:

Beninese female [03]

Burkinabe male [12]

Numerous migrants reported being discriminated against in both Libya and Algeria.

Nigerien male [12]

Half of the respondents reported being extorted at some point of their journey, mostly by the police, their smugglers, as well as managers of detention centres.

Nigerien male [03]

Nine in ten females reported incidents of extortion and five in ten reported being robbed at some point during their outward journey. Robbery was the most witnessed incident reported, with one in four respondents having witnessed at least one occasion where fellow migrants were robbed. Incidents of extortion or robbery were in many occasions followed by physical or sexual abuse.

Sudanese male [39]

Sudanese male [35]

Malian male [06]

Cameroonian male [02]

Five in ten females reported being sexually abused during their outward journey ordeal.

Burkinabe male [02]

It seems likely that males do not feel comfortable sharing experiences of sexual abuse; only one male respondent reported having been sexually abused, although anecdotal evidence supports that it is not as uncommon as one might expect for men to be sexually –and not only physically- abused during the journey.

Sierra Leonean male [01]

Ivorian male [05]

Although the majority of perpetrators of such acts of violence were reported to be armed men along the routes or managers of ghettos and detention centres, female respondents reported being raped by other migrants in ghettos.

Sudanese female [05]

Togolese female

Six in ten women and four in ten men reported that they had been arbitrarily arrested and detained at some point during their outward journey. It was reported that the conditions in these centres were deplorable, as people were given food once a day and were systematically abused, both physically and sexually, by those running the detention centres and unidentified armed groups, referred to as ‘militias’. During their incarceration, migrants were subjected to several other types of abuses and severe human rights violations.

Malian female [03]

Burkinabe female [03]

Burkinabe female [02]

Sudanese male [23]

Burkinabe female [02]

There were also occasions were minors were - systematically - sexually abused.

Nigerien female [03]

Several reported incidents of slavery, forced labour, and torture.

Sudanese male [11]

Ivorian male [07]

Burkinabe male [06]

One in five respondents mentioned witnessing the death of a fellow migrant during their outward journey. Some reported such incidents as being a natural death, caused mainly due to severe dehydration, starvation, or illness, hence holding no one accountable for them. However, there were several respondents who supported that fellow migrants have been exploited and abused so much that this might have played a role in their death.

Sudanese male [19]

Sudanese male [24]

Beninese male [03]

Several reported migrants being killed. The majority of deaths witnessed took place either in the deserts of Niger, Libya, Sudan, Algeria, Chad, or in detention centres in Libya.

Burkinabe male [11]

Ivorian male [02]

Agadez from above - © Xchange.org 2018

Return Journey

From a total of 187 respondents, 131 (70%) departed from Libya, 54 (29%) from Algeria, and two (1%) from Morocco. Overall, the spatial information collected allowed for 185 return journeys to be mapped.

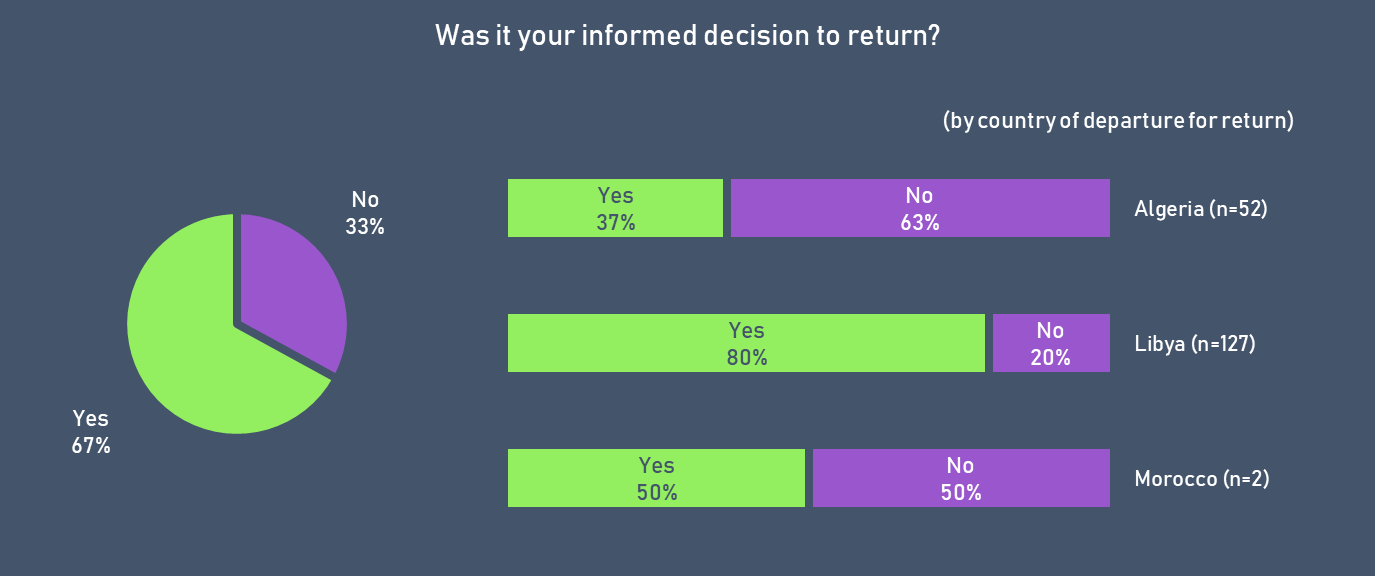

Decision to return - © Xchange.org 2019

Respondents were asked whether it was their own decision to leave Libya, Algeria, or Morocco and start heading towards Niger. Two in three (122 or 67%) respondents said that it was their own decision to return, while one in three (60 or 33%) stated they were forced to. Of those leaving Libya, the vast majority (80%) stated it was their own decision to return. In comparison, only 37% of those returning from Algeria did so because they wanted to, which reinforces the view that the Algerian military has been carrying out mass deportations of migrants.

Nigerian male [09]

Sudanese male [39]

UN presence. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Those who said they were forced to return were asked who took that decision. Except for a few respondents who returned for personal reasons, stating circumstances like “it was my husband’s decision”, or “I lost my mother and wanted to come back”, most respondents (55, or 92%) held the Libyan and Algerian authorities responsible. It is important to notice that a large number of those who reportedly made the decision to return themselves did so due to a lack of financial means or because the experiences of exploitation and abuse they had lived through made them see no alternative.

Ivorian male [02]

77% of those who had left their countries with an identification document were still in possession of the same document when the survey took place. A substantial 33% (35 individuals), however, said they had either lost it in Libya or Algeria, or had it been taken away by the Libyan or Algerian authorities.

Ivorian female [01]

Sudanese male [42]

Beninese male [04]

Those who left their country without an identification document were asked whether they now possess any form of ID. Almost half (10) of those respondents replied in the affirmative, most of whom have only a ‘case number’ issued by the UNHCR.

135 respondents (72.6%) departed from Libya or Algeria in 2018, including all female migrants; 47 respondents (24.7%) departed in 2017; only five respondents (2.7%) departed before 2017. Most of those returning from both Algeria and Libya in 2018 (84% and 55%, respectively) departed in the second half of 2018.

Return journey routes

Map showing all return routes used by the respondents.- ©️ Xchange.org 2019

Many respondents arrived in Agadez on their way back from the north of Africa, taking a similar route to the one they originally took when travelling north. As most returnees departed from Libya and Algeria well after the implementation of Law 2015-036, military presence in the region had significantly increased in line with mounting securitisation in the region, in comparison to when they first attempted to travel northbound before the crackdown on the migration industry started. Many migrants returning from Algeria or Libya were accompanied by military forces.

Algeria-Morocco

Map showing the routes followed by migrants returning from Algeria and Morocco - © Xchange.org 2019

As expected, no respondents leaving Algeria or Morocco crossed into Libya before entering Niger. Almost all Algerian routes converged on either Tamanrasset or Djanet. In the vast majority of cases, returnees headed southwards and crossed into Niger from two main locations, either from Assamakka or from south of Djanet by the border with Libya.

Interestingly, there were return routes that were not mentioned in the outward journeys, particularly from returnees who were not forcibly returned. This might indicate that these routes were used to avoid detection by the Nigerien authorities due to the higher police presence. Typical examples are the direct routes from Djanet to Madama. Others mentioned routes already taken on their way to Libya and Algeria, as can be the case of those from Djanet or Tamanrasset directly to Arlit, avoiding detection in In Guezzam and Assamakka.

Algiers by night - © Xchange.org 2019/Ioannis Papasilekas

Libya

Map showing the routes followed by migrants returning from Libya - © Xchange.org 2019

The majority of respondents returning from Libya transited Al Wigh in the south of the country and entered Niger from the usual entry point of Madama, continuing to Dirkou and Seguedine before arriving in Agadez. Their routes converged in Qatrun, Libya, irrespective of which city they departed from. Two Nigeriens, however, reported returning directly from Ghat, Libya, entering Niger from close to the Algerian border without crossing it.

Several others leaving Libya crossed into Algeria (Debdeb or Djanet) from Ghadamis or Ghat before entering Niger, very likely in an attempt to avoid detection by the Nigerien authorities deployed close to the border in Libya. From there, they continued via Tamanrasset and In Guezzam to Assamakka or directly via Djanet headed to either Madama or Arlit via the mountainous region of northwest Agadez. One Beninese leaving Ghat did not follow the usual route to Djanet, but went north towards Illizi, from where he went southwest to Tamanrasset via Borj El Haouas. One Burkinabe flew to Niamey from Tripoli and from there he went by car to Agadez.

Niamey to Agadez aerial photo - © Xchange.org 2018

Modes of transport

On average, respondents used either one or two modes of transport to reach Agadez; 91 (51%) used a truck, 80 (45%) car, 48 (27%) SUV, 45 (25%) bus. Compared to the outward journey, where the most common means of transport was the car, the majority used a truck to return, irrespective of which country they departed from.

Starvation and Dehydration

On average, the return journeys were much shorter in length than the outward. This, coupled with the fact that the majority of respondents were accompanied by figures of authority, led as expected to fewer experiences of dehydration or starvation. One in ten (11%) migrants reported starving during their return journey and one in twenty (5%) reported feeling dehydrated.

Poste de Police. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Incidents during return journey

The vast majority of respondents supported that they did not experience any major incident or human rights violation on their way south towards Agadez. They attributed this to the fact that they were accompanied by either the Algerian or the Libyan authorities, police, or military.

Beninese male [03]

Nigerian female [05]

Beninese female [05]

Nigerien male [06]

However, there were several who, despite being accompanied by state forces, witnessed cases of robbery or extortion, saw dead bodies, or were abandoned in the desert and suffered from physical and/or sexual abuse. Similar experiences were told by those who returned from Libya and Algeria with the help of a passeur or coxeur.

Burkinabe male [07]

Migrants were extorted.

Sudanese male [39]

Abuse of multiple forms was also prevalent during the return journeys, mostly following extortion and robbery incidents.

Sudanese male [38]

Burkinabe male [02]

Ghanaian male [01]

Rainy Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

According to the survivors, several incidents during the return journey happened within Niger itself.

Sudanese female [05]

Sudanese male [21]

A few were detained after being caught by the Nigerien police while entering Niger.

Sudanese male [22]

During the return journey fewer migrants witnessed the death of someone in the desert compared to the outward journey. It is important to mention, however, that these few respondents witnessed death in the region of Agadez on their way from Libya, between Dirkou and Madama.

Burkinabe female [01]

Malian male [12]

Ivorian male [09]

Sudanese male [18]

Sierra Leonean male [01]

Feelings of safety in Agadez

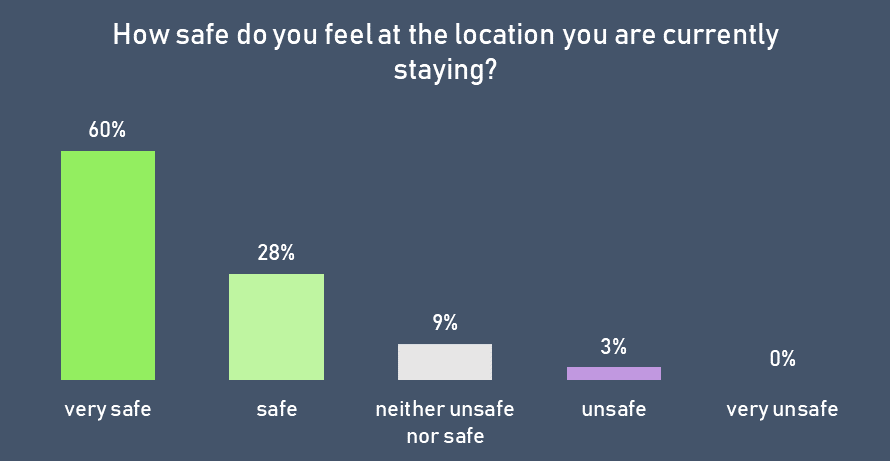

Feelings of safety at temporary home (in Agadez) - © Xchange.org 2019

Respondents were asked how safe they felt living in Agadez, and in particular at the place they were staying in temporarily. Overall, most respondents felt either very safe or safe in Agadez (88%). In more detail, 108 (60%) reported feeling very safe, 50 (28%) safe, 17 (9%) neither unsafe nor safe, only 6 (3%) unsafe, and none very unsafe.

Burkinabe male [07]

Mano Dayak street. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

On the other hand, frustration was apparent, particularly among Sudanese asylum seekers who, despite feeling relatively safe where they were staying, did not know what the future holds for them.

Sudanese male [14]

Sudanese male [16]

Contact with family in country of origin

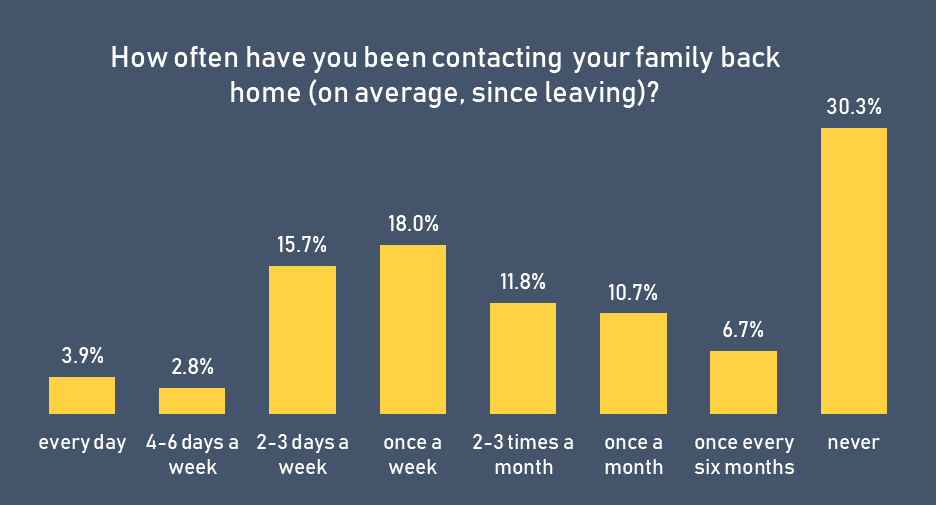

Frequency of contacting family in country of origin - © Xchange.org 2019

A large number of migrants (54, or 30.3%) supported they had not contacted their family back home since they began their journey. 40.4% of respondents had been contacting their families back home at least once a week. Only 7 respondents (3.9%) reported contacting their family every day since leaving their home country.

Of those who said that they had been primarily contacting their families at least once every six months (70%), the vast majority (89, or 72%) were using their own mobile phones as the main means of communication, 23% (28) would borrow other migrants’ phones, while the rest (5%) would contact them from internet cafes, public telephone booths, or from shops. Of those who said they have not contacted their families, some explained that it was either due to them not having a phone or their family’s phone numbers, with many admitting that they did not want to get in contact due to feeling embarrassed for not making it to their intended destination, or because they lost everything before they began their return to Agadez.

Carrier. Agadez - © Xchange.org 2018

Vision for the future

Evaluation of migration experience

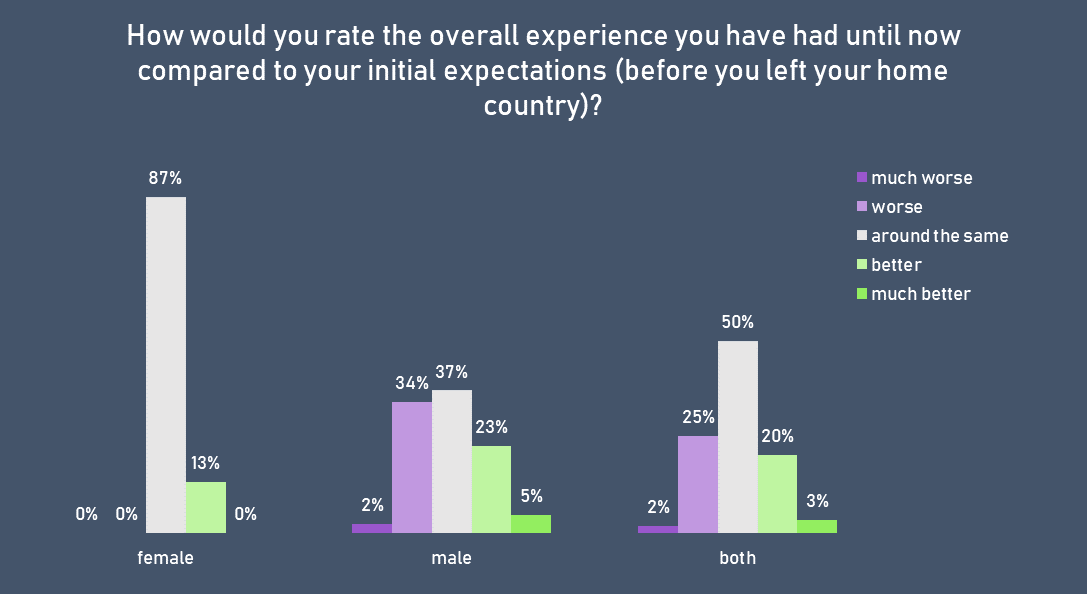

Evaluation of overall migration experience - © Xchange.org 2019

Migrants were asked to evaluate their overall experience; from the decision to leave their home country until the moment the survey took place. The sample was divided into those who felt that their experience was similar to what they had expected (50%), and those who thought it was either worse or better (50%). Of those who felt it was either worse or better, respondents were also divided. However, none of the female respondents felt their overall experience was worse or much worse than their initial expectations; 87% of female respondents expected their journey to go as it did. This might imply that when people decided to migrate, their expectations were quite low in the first place. 36% of males, on the other hand, had a worse or much worse experience from how they expected it to be.

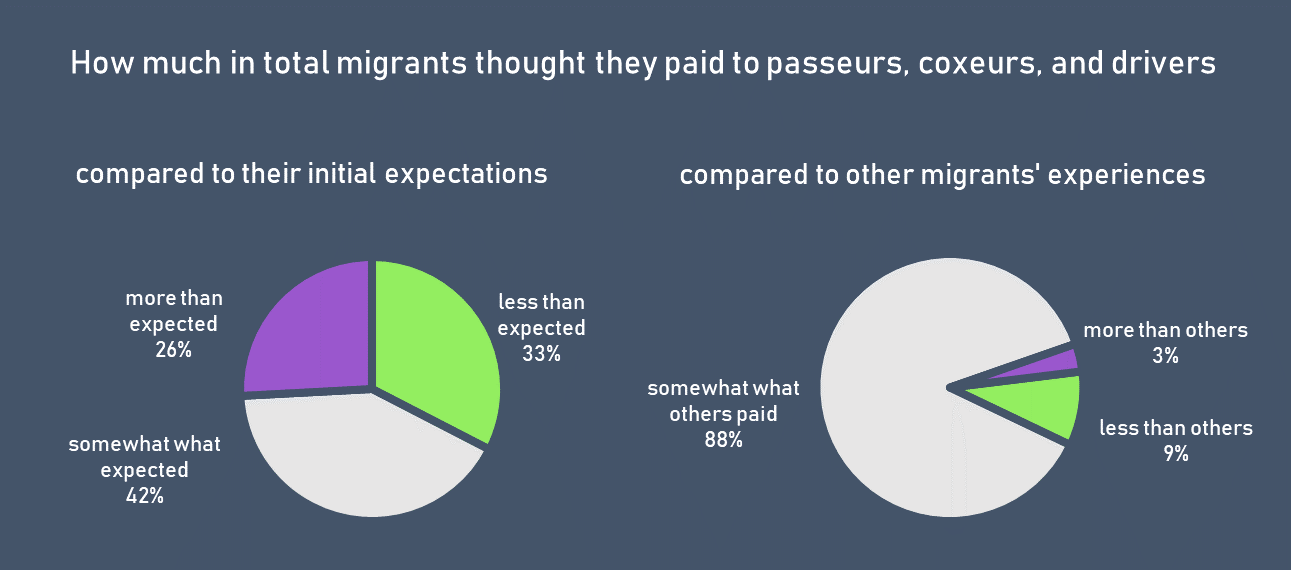

Paying passeurs, coxeurs, and drivers - © Xchange.org 2019

With regards to how much they think they spent in travel costs compared to their initial expectations, 42% of the sample paid as much as they expected, 33% paid less than what they thought the journey would have cost, and 26% paid more.

Liberian female

They were also asked to evaluate how much they think they paid to drivers, passeurs, and coxeurs based on the knowledge they had on what other migrants paid them. Here, the vast majority (89%) reckoned they paid as much as others. 9% however disagreed, believing that they were fortunate to have paid less than others.

Burkinabe male [07]

Burkinabe female [03]

Nigerien female [04]

Sudanese male [39]

A mere 3% thought they paid more than other migrants. No female respondents thought they paid more.

Sudanese male [11]

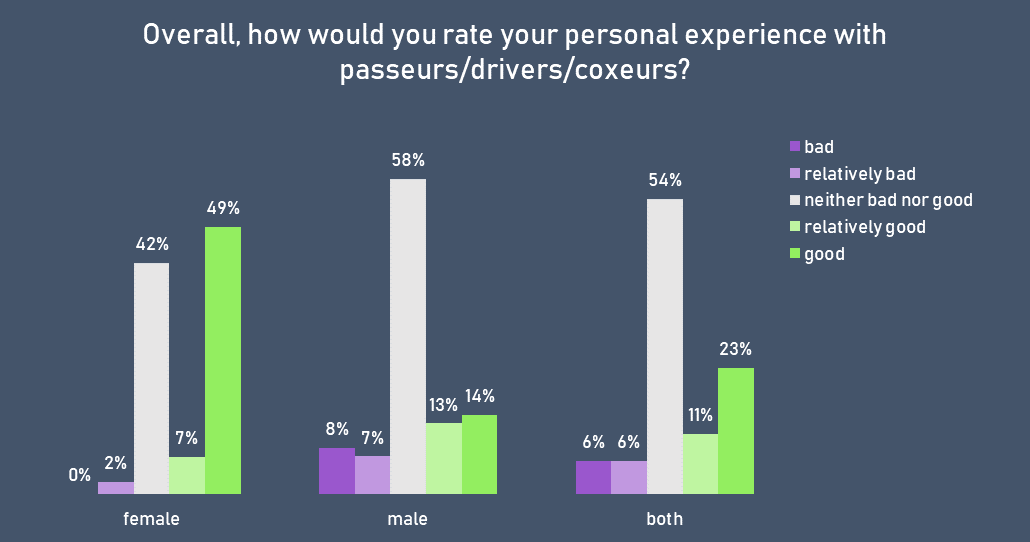

Evaluation of overall experience with passeurs, coxeurs, and drivers - © Xchange.org 2019

54% of the sample felt that their overall experience with passeurs, drivers, and coxeurs was neither bad nor good, 34% leaned towards ‘good’ (11% relatively good, 23% good), 12% leaned towards ‘bad’ (6% relatively bad, 6% bad). Interestingly, more female respondents (both in absolute and relative numbers) thought they had an overall good experience compared to male respondents (56% of females supported good or relatively good, 27% of males stated good or relatively good).

Spices. Agadez Market - © Xchange.org 2018

Plan for the near future

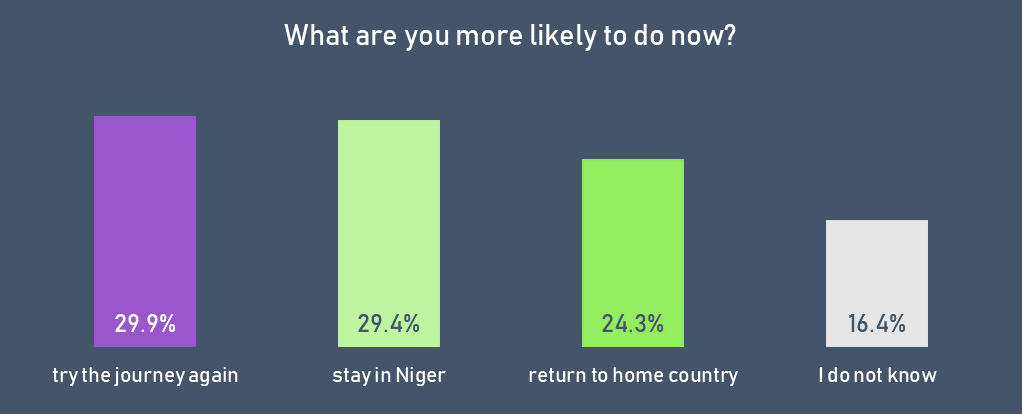

Plan for the near future - © Xchange.org 2019

Respondents did not act as a unanimous group when they were asked what their plans for the near future are. Interestingly, 53 out of 177 respondents (29.9%) stated they would like to continue their journey; go back to Libya or Algeria and perhaps try to cross the Mediterranean. Two in three Nigeriens belonged to this category, stating they will leave Niger again soon.

Ivorian female [01]

Sudanese male [10]

Agadez streets - © Xchange.org 2018

52 respondents (29.4%) were keen on staying in Niger either until they are given options or be able to decide for themselves.

Sudanese male [02]

Liberian female

29 migrants (16.4%) did not know what the future holds for them. Only one in four migrants (43 or 24.3%) stated they are more likely to return to their home country than do anything else.

Malian male [01]

Sudanese male [23]

Recommendations for others who think of migrating

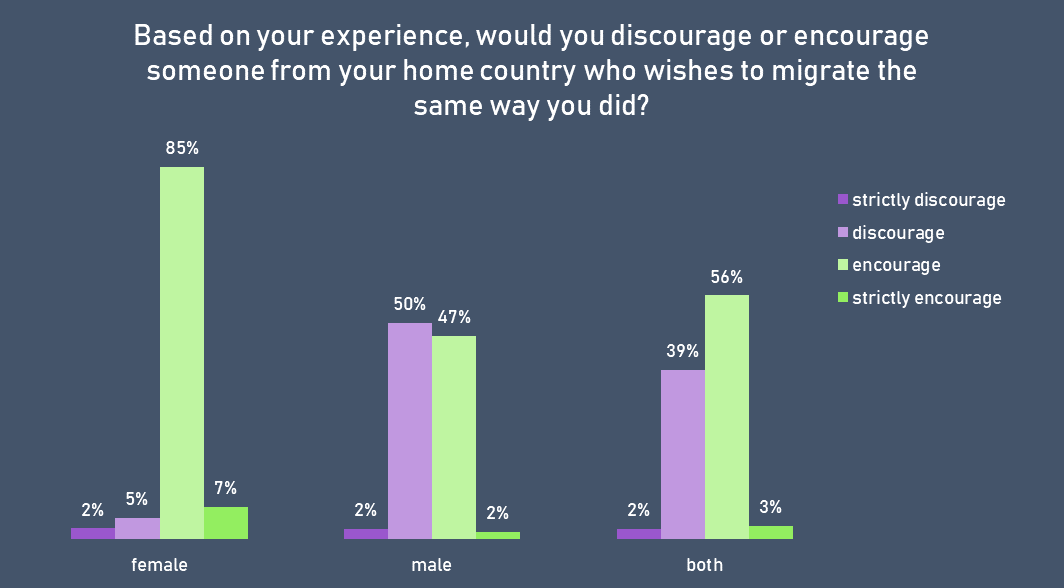

Encouragement/Discouragement of others who think of migrating - © Xchange.org 2019

100 out of 170 (59%) would encourage or strictly encourage other people from their country of origin to try the same journey based on their own experiences. Male respondents’ opinions were divided, whereas 93% of female respondents would encourage or strictly encourage others to try the journey, potentially respective of the fact that in their majority they were being repatriated against their will. This high number of people encouraging others is corroborated by testimonies given by stakeholders in the region.

As reported by Program Coordinators of both International and Nigerien NGOs, migration is the last resort in the fight for survival for many young people from West African states. Many were those respondents who would encourage young people to seek a better future, even if that meant they would have to risk their lives.

Burkinabe male [10]

Burkinabe female [02]

Nigerien male [01]

Nigerien male [14]

Malian male [12]

Several respondents gave specific advice:

Ivorian male [03]

Malian female [01]

Nigerien female [03]

However, a majority of male respondents in particular advised against all travel towards Libya.

Ivorian male [06]

Burkinabe male [01]

Beninese male [07]

Beninese male [06]

Ivorian male [07]

Sudanese male [19]

Sudanese male [24]

Sudanese male [26]

Others would support people’s decisions to migrate but advise them against getting on a boat to Europe. They maintained that young people should consider staying within the African continent.

Sierra Leonean male [02]

Sudanese female [02]

Nigerians from the region of Bauchi State wanted to inform people from their region of origin regarding the possibility of staying in Niger, where they can feel safe.

Nigerian male [16]

Taxi drive in Niamey - ©️ Xchange Foundation/Ioannis Papasilekas - 2018

Conclusion

In late 2018, Xchange was in Agadez, Niger, to investigate what happens to those migrants who either did not plan to cross the Mediterranean Sea in the first place or did not manage to do so successfully. Over the course of one month, we conducted a survey with 189 migrants in transit from 17 African countries who had already been to Libya and/or Algeria and were technically on their way back to their countries of origin, hence 'returnees'.

Agadez has long played a crucial role as a transit hub for Sub-Saharan Africans travelling northwards, towards Libya and Algeria, or southwards. This was supported by the fact that 80% of those interviewed who departed for their journey between 2015 and 2018 (excluding the Sudanese, who in their majority went to Libya either directly or via Chad) transited Agadez before arriving in Libya or Algeria.

After the implementation of Law 2015-036, smugglers, drivers, and the migrants they transport have started taking longer, alternative routes. This, in turn, has made the once-identified patterns of migratory routes across Africa more complex and difficult to map. Several of our respondents used 'irregular' routes to reach Libya or Algeria, avoiding checkpoints and crossing the borders through the desert. The border where Algeria, Niger, and Libya meet was particularly used as a crossing point; migrants would cross from Madama, Niger straight into Ghat, Libya on their journey into Libya, and from Djanet, Algeria to Madama, Niger upon their return. Checkpoints like in Assamakka in Niger were reportedly avoided on several occasions during both outward and return journeys. The vast majority of migrants experienced and witnessed human rights abuses during their ordeals, both en-route and while in Libya or Algeria, where many spent time in detention centres.

Before starting their journeys, 44% of the sample expressed their intention to stay within Africa (Libya, Algeria, Morocco, Niger), 43% intended to go to a European country, 11% stated they would go anywhere where they could feel safe, and 1% wanted to go to the USA. One in four (24%) migrants tried to cross the Mediterranean Sea at least once but failed, and either were discouraged and headed south toward Agadez or were deported.

One in three (33%) respondents returned to Niger against their will, refouled by the Algerian or Libyan authorities. However, only one in four (24%) intended to leave Niger and go back to their country of origin at the time the survey took place. 29% thought it was more likely for them to stay in Niger. The largest group (30%) was comprised of those who, on the other hand, intended to leave Niger and try the journey anew. This finding could be considered ironic as all interviewed migrants were 'returnees' or 'migrants in return'.

In conclusion, half of the migrants we interviewed thought that their overall migration experience up until the time the survey took place was similar to what they had expected before they had left their countries of origin — the vast majority of female respondents belonged to this category. The rest were divided between those whose experiences slightly exceeded their expectations and those who regretted leaving their home. As a result, many would encourage young Africans to continue seeking a better future outside their home countries, but advise them strongly against doing so in Libya.

Beninese male [02]

Malian male [03]

Agadez sunsets - © Xchange.org 2018

Key Concepts and Definitions

Asylum seeker

The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) defines ‘asylum seeker’ as a person who seeks safety from persecution or serious harm in a country other than his or her own and awaits a decision on the application for refugee status under relevant international and national instruments.

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) defines ‘forced labour’ as all work or service which is exacted from any person under the threat of penalty and for which the person has not offered himself or herself voluntarily.

Migration as a result of coercion or threat, including to life and livelihood, which can arise from natural or man-made causes.

For the purposes of this survey, an incident refers to an event, either witnessed or experienced, which either involves violation of human rights or crime or dangers which may lead to death but is not classified as a human rights violation (such as dying from dehydration in the desert), or which is a direct consequence of another incident such as being subjected to degrading treatment while detained.

According to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), irregular migration is “movement that takes place outside the regulatory norms of the sending, transit and receiving countries .” However, there is no universally accepted definition of the term.

IOM defines a migrant as any person who is or has moved across an international border or within a state away from his/her habitual place of residence, regardless of (1) the person’s legal status (2) whether the movement is voluntary or involuntary (3) what the causes for the movement are, or (4) what the length of the stay is.

There is no legal definition of a migrant in transit – OHCHR acknowledges they may include refugees, asylum seekers, economic or climate migrants – they fall under different forms of international protection. However, they are all vulnerable to the same human rights violations while in transit. For the purpose of this report, the term “migrant” refers to all people on the move encountered in this research, including refugees, economic migrants, asylum seekers, unaccompanied or separated minors.

Article 3 of the UN Protocol Against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea, and Air defines ‘migrant smuggling’ as the "procurement, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit, of the illegal entry of a person into a State Party of which the person is not a national or a permanent resident ." Smuggling, contrary to trafficking, does not require an element of exploitation, coercion, or violation of human rights.

A complex migration flow containing various types of migration motives and migrants including asylum seekers and refugees (forced migrants), economic migrants, climate/environmental migrants, stateless persons, unaccompanied migrants, trafficking victims.

The 1951 Refugee Convention defines a refugee as “an individual who is outside his or her country of nationality or habitual residence who is unable or unwilling to return due to a well-founded fear of persecution based on his or her race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.”

‘Slavery’ is described by Anti-Slavery International as the act of being owned and controlled by an 'employer' through mental and physical abuse, or threats of abuse. Article 1 of the League of Nations Slavery Convention of 1926 first defined slavery as “the status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised”. Nowadays it is described as incorporating all activities of child slavery, forced and early marriage, forced labour, debt bondage, human trafficking and descent-based slavery.

Article 1 of the United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment is the internationally agreed legal definition of torture: "Torture means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions."

Article 3, paragraph (a) of the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons defines ‘trafficking in persons’ as the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs. Trafficking in persons can take place within the borders of one State or between different States.

Economic Community of West African States. “ECOWAS is a 15-member regional group with a mandate of promoting economic integration in all fields of activity of the constituting countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Cote d’ Ivoire, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Senegal and Togo.”

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, which assists and protects refugees worldwide, striving to "ensure that everyone has the right to seek asylum and find safe refuge in another State, with the option to eventually return home, integrate or resettle." The organisation also provides emergency assistance (water, shelter, non-food items, healthcare, etc.).

Acknowledgements

Coordination, Research, GIS Mapping, Analysis, & Report writing: Ioannis Papasilekas

Report writing: Maria Fatas Ortega

Project funded by moas.eu

Contact Us

As an information and research initiative, we are eager to work with a wide spectrum of stakeholders to exchange information and knowledge.

We are looking for partners and funding organizations to support us in conducting a new round of surveys. Please, feel free to send us your proposals.

Copyright © Xchange.org 2019