"Abroad means difficult..."

In July 2019, Xchange conducted 17 in-depth interviews in Malaysia with Rohingya refugees. The findings are presented in this video-report.

Introduction

Departure: Bangladesh

During 2018 and 2019, Xchange explored the living conditions and issues which both new arrivals and more long-term resident Rohingya were facing in the refugee camps in Bangladesh. The Rohingya Survey 2019 focused on assessing the living conditions in the camps from the perspective of the Rohingya and explored their attitudes towards living in Bangladesh; 98% of respondents often felt stressed or overwhelmed by their living situation, whilst 41% felt at home very little and 47% did not feel at home at all in their camp in Bangladesh. Unsurprisingly, almost one in three Rohingya (31%) admitted to considering an onward movement to another country, with 6% being determined to attempt to flee with the help of a human smuggler. The top desired countries of destination were in order of preference: Saudi Arabia, Canada, USA, Australia, Turkey, and Malaysia.

Destination: Malaysia

Being a Muslim-majority country with a dual justice system that incorporates Sharia law, Malaysia has long been an attractive destination for Rohingya Muslims seeking a prosperous future outside the cramped refugee camps of Bangladesh. Despite ranking only sixth in the respondent’s preferences in the Rohingya Survey 2019 Malaysia was geographically the closest country to Bangladesh, and hence the most affordable for Rohingya to go to. Moreover, two thirds of respondents who were in regular contact with a Rohingya abroad stated they had a family member or friend in Malaysia. The likelihood of a Rohingya choosing Malaysia over other countries could therefore be considered quite high.

Traditionally, Rohingya refugees have been reaching Malaysia by boat, crossing the Andaman Sea and Strait of Malacca either directly or via Thailand. Following a recent increase in maritime patrols by the Thai authorities, boat traffic in the Andaman Sea has been relatively reduced and the crossing has become a risky endeavour. As a result, the desire to escape the refugee camps has led many Rohingya towards seeking alternative ways.

In the last two years, more and more cases of Rohingya attempting to reach Malaysia by air and land have come to light; several have been detained at airports in Bangladesh and India, while a few manage to cross the border to India or get on a plane to Kuala Lumpur on forged Bangladeshi passports.

The Rohingya refugee situation in Malaysia

As of the end of April 2019, there are some 90,200 Rohingya refugees registered with UNHCR in Malaysia. Most Rohingya end up living in the northern states of Perlis, Kedah, and Kelantan (which act as transit points from Thailand), the states of Penang and Johor, as well as Kuala Lumpur and its suburbs.

Malaysia does not recognise the Rohingya as refugees – it lacks the legal and policy infrastructure to do so; the country has not signed the UN 1951 Refugee Convention, nor its 1967 Protocol (nor the 1954 and 1961 UN Statelessness Convention), meaning it is under no obligation to provide support and access to services. Even when registered as refugees with the UNHCR, refugees continue to be at risk of deportation as the cards granted by the UN do not constitute official documentation.

As a result, Rohingya refugees cannot access the formal labour market or public education even when recognised as refugees, and their access to public healthcare is limited. Hence, most Rohingya in Malaysia are irregularly occupied in industries such as agriculture, construction, textile manufacturing, or recycling scrap metal. Due to their vulnerability and uncertain legal status, cases of exploitation and human trafficking are not rare.

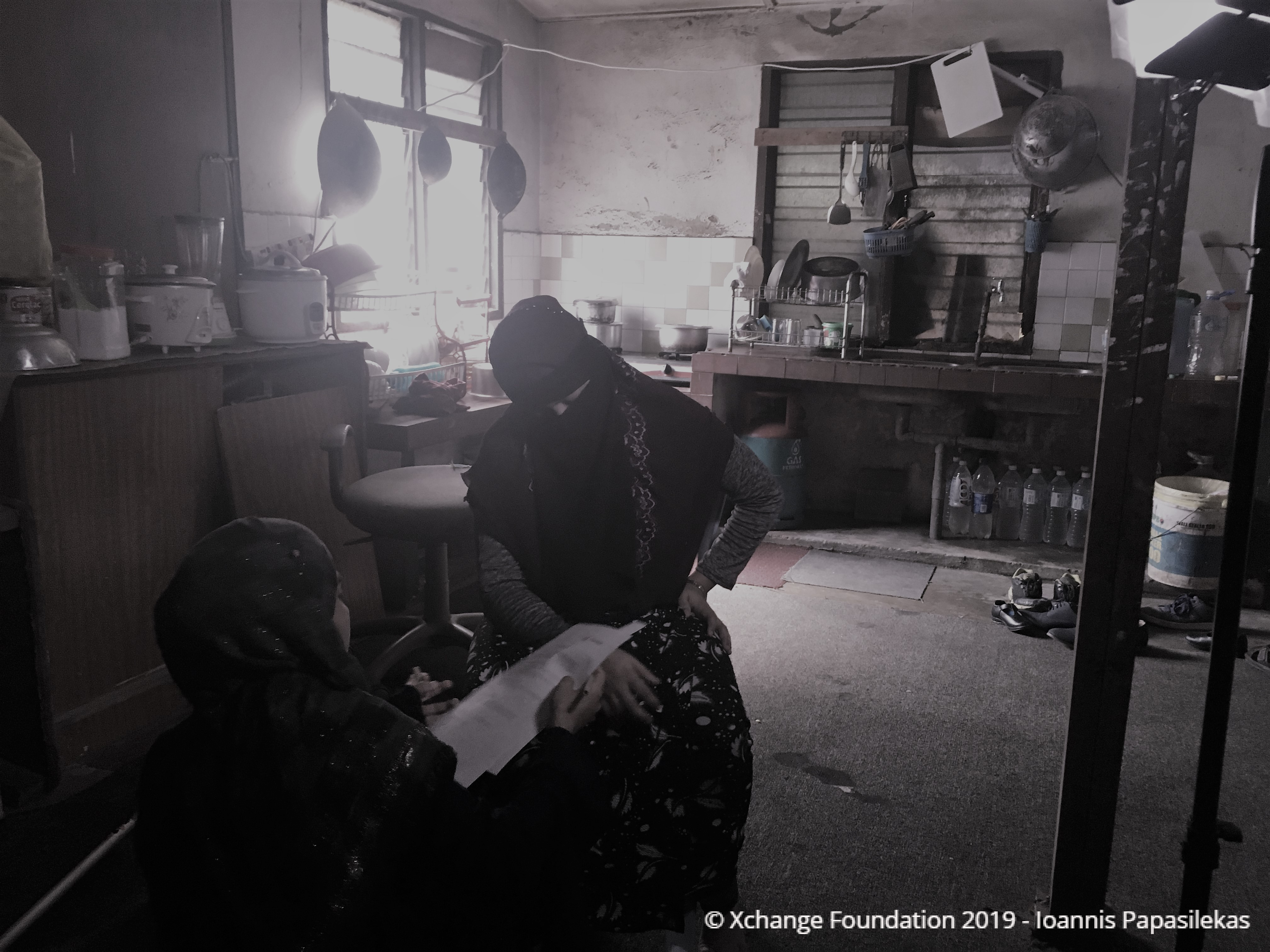

Refugee accommodation in Penang, Malaysia, July 2019

Methodology & Research Implementation

Research Objective

Building on the Rohingya Survey 2019, the aim of this video-report is to:

- Understand the push and pull factors which led Rohingya refugees to consider leaving their camps in Bangladesh,

- Investigate the means and connections they utilised to leave the country,

- Explore what the journeys they undertook entailed, and finally

- Give an overview of how life for the Rohingya community in Malaysia is and how they feel towards the situation in Bangladesh refugee camps.

Research Design & Data Collection

Over the course of two weeks (July 2019), Xchange conducted 17 in-depth interviews with Rohingya refugees residing in Kuala Lumpur, its outskirts, Butterworth, and Penang island, Malaysia. The data collection team comprised of an Xchange Researcher, a Rohingya cultural mediator, and a videographer.

The interviews were carried out with the use of a semi-structured interview guide either in Rohingya (12 interviews) or English (five). On average, each interview lasted 45 minutes. All 17 interviews were audio-recorded; 16 were also filmed.

Participants were familiarized with the purpose of the study in advance and were informed that participation was entirely voluntary and that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any given time. Immediately before each interview, written consent was explicitly collected for both the audio- and the video-recording of the interviews; all participants were given the option to disagree with being on camera (one participant) or not show their faces (five participants) and have their voice changed (one participant). Finally, all participants’ names were replaced with pseudonyms and all names of locations were excluded from the video-report.

Once the data collection had finished, the interviews were translated into English and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were subsequently coded and analysed thematically. The findings of the coding and the analysis are presented in the video-report.

Collecting personal information and Informed Consent, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, July 2019

Sample Description

Participant recruitment was done through snowball sampling initiated by a female Rohingya refugee who had also fled Bangladesh and was in Malaysia at the time. The snowball sampling was continued until saturation was achieved. This was in order to ensure a diverse, albeit non-representative sample, and to capture a holistic picture of the Rohingya diaspora’s experiences in Malaysia. The sample comprised of 13 male and four female participants, aged between 18 and 60 years, with a median of 26 years. Nine participants were born in Myanmar while eight were born in Bangladesh. All participants had moved to Malaysia from Bangladesh; 12 left Bangladesh prior to 2017 and five left after 2017. Their time in Bangladesh ranged between five weeks and 26 years, while their time in Malaysia ranged between seven months and eight years.

List of participants - © Xchange.org 2019

The male participants’ occupations included grasscutter, general factory worker, English and Mathematics tutor, interpreter, councillor, drain and street cleaner, and shopkeeper. The oldest participant was not employed, and one other male had recently resigned from his job. All four female participants were unemployed. Nine participants were married, one was divorced and seven were single at the time of data collection. A majority had received basic education or none, while five had finished class ten in either Myanmar or Bangladesh.

Limitations

A pre-arranged 18th interview was conducted. Due to time constraints during the transcription and translation phase, this interview was excluded from the analysis and the final report. Since saturation had already been reached, the Research team considered that this interview would not add new aspects to the findings.

As some of the interviews were conducted in English, this might have played a negative role on the quality of the collected information. For the interviews conducted in Rohingya, questions and replies were translated from English to Rohingya and from Rohingya to English respectively. Despite the rapidity of these translations, it did present some difficulties when maintaining the flow of the interview. For the same reason, building rapport with some interviewees also became a challenge.

Findings

Video-presentation of the findings - ©️ Xchange Foundation 2019

In this video-report, Xchange explores the experiences of Rohingya who fled refugee camps in Bangladesh either by boat, land, or plane on fake passports and investigates what life entails for the Rohingya community in Malaysia.

Push and pull factors

There was an array of push factors identified that caused participants distress in Bangladesh and made them seek livelihood abroad. These included restrictions of movement, employment, and formal education. A few participants referred to their former residence as ‘concentration camps’; Rohingya in Bangladesh are not allowed to move outside the camps freely and need to follow certain restrictive and often changing rules. For younger participants, the main reason leaving Bangladesh was the limited formal and secondary education options, as well as the prohibition against working formally which prevented them from making a living. They felt they were always dependent on humanitarian assistance which intensified their sense of financial uncertainty. A majority stated they would often be discriminated against by Bangladeshi locals and even falsely accused, extorted, arbitrarily arrested, and incarcerated by the Bangladeshi authorities for crimes they allegedly were not aware of. To avoid the potential for such unfavorable situations, participants would often conceal their Rohingya identity among the Bangladeshi population, which only intensified their feelings of insecurity in Bangladesh.

Abdul Aziz

Ali Johar

Regarding pull factors, geographic proximity to Bangladesh made it easier and more affordable for interviewees to move to Malaysia than to another country. Apart from a few participants who were not well-informed about the situation in Malaysia prior to their arrival, most had a relative or friend already living in the country who kept them up-to-date and made emigration to Malaysia appealing as they could assist them upon arrival. Moreover, Malaysia being a predominantly Muslim country attracted the Rohingya who sought a place where they could practice their religion and culture without fear of religious persecution.

Several interviewees viewed Malaysia as a temporary destination; they knew in advance that the Government does not recognize refugees but also knew that UNHCR has a strong presence in Malaysia and lobbies for refugee relocation. This attracted many Rohingya who wished to be resettled to another country such as the USA, Canada, Australia, and Norway as their chances to do so from Malaysia rather than from other countries were perceived to be much higher.

Md Rafik

Younger participants moved to Malaysia hoping they would be able to receive secondary and tertiary education. Reportedly, rumors had been spread in Bangladesh that the education system in Malaysia accepts everyone. Participants realized refugees are not admitted to the Malaysian education system only after their arrival.

Yusuf Ali

View from Rohingya participant's accommodation in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, July 2019

Journeys

Twelve of the interviewed Rohingya had been living in Malaysia for between two and eight years at the time of the interview. Prior to 2017, leaving Bangladesh for Malaysia irregularly was facilitated by human smugglers mostly by boat via the Andaman Sea. Most participants going by boat said they were ‘following the trend’ of people leaving.

Salim Abdul

Participants referred to the people who arranged their travel from Bangladesh to Malaysia as ‘smugglers’, ‘agents’, and ‘traffickers’ interchangeably, indicating that for them the boundaries between smuggling and trafficking are blurred. This inability to distinguish between the two highlights in turn that Rohingya were at high risk of exploitation by people they would initially trust. Older participants had contacted their smuggler themselves to arrange their journey, while for the majority, the journey was arranged by someone in their family or a close friend. A few participants kept the move secret from their families. However, they recognized afterwards that this has put a financial strain on their families since there was a need to cover their journeys’ expenses by borrowing money they did not have.

Yusuf Ali

Unsurprisingly, no Rohingya refugee was required to show documentation to their smugglers to cross international waters and borders. Most participants, however, held onto a copy of their UNHCR card of Bangladesh to facilitate the refugee registration process with the UNHCR in Malaysia.

The journey was twofold for most and involved a stop in Thailand, which generally lasted for several weeks. During this time, they were moved from place to place to avoid detection by the Thai authorities. Participants were unaware of the exact locations they were taken to, referring to them as ‘the jungle’ or ‘the forest’, ‘the isolated island’, and ‘the mountain’. From there, interviewees either boarded another boat or continued by land, either with or without the help of local smugglers.

The financial cost of the journey was generally quite high. Participants disclosed they paid the equivalent of more than two thousand euros for the irregular boat journey from Bangladesh to Malaysia. Most of them had to pay for the first part of their journey in the form of ransom while they were in Thailand. They were kept in cramped ‘wooden houses’ by their smugglers until their families and friends managed to borrow money and pay the ‘debt’.

Md Roshid

Throughout the journey, there was no interviewee who had not experienced or witnessed incidents of human rights abuses, including murder, rape, beatings, enslavement, and torture, either on the way to or in Thailand.

Md Rafik

Muhib Nur

The five participants who had been in Malaysia for fewer than 24 months at the time of the interview did not use a boat as their main transport means; rather, they used fake passports and alternative modes of transport by air, land, or sea. They all followed different itineraries. Three had departed from Dhaka airport on different occasions during the last two-year period using forged Bangladeshi passports: one flew directly to Kuala Lumpur airport in Malaysia; one flew to Bangkok, Thailand, from where he continued by land; and one flew to Indonesia via Kuala Lumpur, was deported back to Bangladesh and tried anew following a similar itinerary. One refugee travelled by land to India, Myanmar, and Thailand before entering Malaysia by boat. The last interviewee was the only one who did not intend to find himself in Malaysia. He left Bangladesh by boat to Myanmar, then lived in Thailand, flew to Cambodia, and on his way to Norway on a fake Myanmar passport was detained at Kuala Lumpur airport. With the intervention of UNHCR, he managed to stay in Malaysia and at the time of the interview he was awaiting a decision regarding his application to relocate to Canada.

Typically, participants going to Malaysia by plane paid more to their smugglers compared to those who left Bangladesh by boat, usually the equivalent of more than two thousand euros excluding the cost of forgery of a passport which, according to one interviewee, cost an additional one thousand euros. Most were deceived either prior to or after their journeys by their respective ‘travel agents’-smugglers, who either ‘took the money and did not deliver’, lied about their itinerary, or stole the participant’s passport in the wake of their arrival in Malaysia.

Rohingya participant's accommodation in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, July 2019

Life in Malaysia

Among participants, the perceived quality of life in Malaysia varied depending on the time spent in the country, work and social environment, as well as Malay or English language skills, among other factors. Overall, all interviewees agreed that their everyday lives among the Malaysian population were good, especially in comparison to how they would be treated in Bangladesh. Malaysians showed compassion towards them and as a result, no participant felt the need to conceal their Rohingya identity in Malaysia.

Md Rafik

Despite the feelings of safety and compassion, integration into Malaysian society is almost impossible, since refugees in general are considered by the Malaysian government to be illegal immigrants. All participants felt at risk of arbitrary arrest and detention by the Malaysian authorities, especially before receiving refugee status. The majority had personally experienced at least one incident of exploitation by the police.

Rahina

Soon after their arrival, all participants reached out to the UNHCR office in Kuala Lumpur and applied for refugee status. The UNHCR card provides Rohingya refugees with the right to move freely within Malaysia, yet this is perceived by interviewees as insufficient to realize one’s aspirations in the host country. One male refugee explained how he attempted multiple times to receive education over his eight-year stay in Malaysia, without success.

Salim Abdul

Others narrated incidents of failed attempts to purchase a phone and a SIM card, open a bank account, or obtain a driver’s license. As a consequence of this, they all felt embarrassed, disappointed, and helpless.

Nur Mostafa

Realizing that their options were limited, younger participants who were in need of education started working to make ends meet instead. All working males reported sending remittances every month to their families back in Bangladesh. As a result, the majority reported they were unable to save a reasonable amount of money for the future. A few participants resorted to working illegally in construction or cleaning services in order to cover their basic expenses.

Ali Johar

These findings emphasize the discrepancy between the needs of refugees and the services available to them, leaving refugees in a precarious position.

Basic accommodation in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, July 2019

Looking into the future

Despite their feelings of insecurity, most participants preferred everyday life in Malaysia to life in Bangladesh. However, the vast majority advised against other Rohingya travelling to Malaysia; they perceived that the irregular journey has become riskier with time. Alas, no participant had a positive view about the future of the Rohingya who still live in Bangladesh either; they all believed that without a national identity and rights the Rohingya in the camps will continue to feel insecure. Interviewees shared a sense of alienation and lack of belonging. They often emphasized that the challenges faced by the Rohingya in Bangladesh are universal and not limited to the refugee camp context. Regarding finding a durable solution to their problems, gaining citizenship ideally from Myanmar or alternatively from Malaysia or any other country was again identified as essential.

Salim Abdul

Abdul Aziz

Salim Abdul

Some participants expressed an overall frustration about the lack of support they had been receiving in Malaysia. Given that Malaysia does not recognize them as refugees, the majority felt in limbo. The lack of protection, education opportunities, and formal assistance by the Malaysian government only intensified the feelings of despair of those participants who were willing to integrate into the host country if they were ever given the opportunity to do so. As a result, participants felt a sense of helplessness and lack of control over their future in Malaysia. Their desire to dream and aspire was thwarted by the inability to secure their basic rights.

Tasmina

Exploitation and eviction by their landlords were not unreasonable fears for participants either; a few have had to change residences within Malaysia which consequently put a further strain on their will to integrate and build relationships. Consequently, some interviewees stated they would return to Bangladesh should they get the opportunity to do so in the near future. The lack of education and job opportunities, as well as the need for social bonds and relationships were among the main reasons why they considered leaving Malaysia.

Md Ullah

Photo Slider: Refugee accommodation in Penang, Malaysia, July 2019

Conclusion

This video-report aimed to provide an overview of the migration experience of Rohingya refugees from Bangladesh to Malaysia as well as an understanding of the life of the Rohingya diaspora in Malaysia. It highlighted the absence of a sufficient policy framework for refugees in Malaysia, where Rohingya refugees could receive quality education, gain skills, identify, pursue, and realize goals, and ultimately improve their livelihood whilst contributing positively to their host communities. Among interviewees, it was recognized that raising the education level among the Rohingya diaspora globally is a necessary first step towards improving their situation overall.

Md Zubair

In summary, we could conclude that there is an imperative need to conceptualize Rohingya refugees as valuable members of society and not merely as inactive victims in need of humanitarian assistance. Participants identified that access to services will alleviate their suffering, help them overcome their insecurities, and mitigate the sense of alienation the Rohingya diaspora experiences world-wide.

Md Ullah

Acknowledgements

Coordination, Research, Analysis, & Report-writing: Ioannis Papasilekas

Peer review: Jeki Whitmey

Contact Us

As an information and research initiative, we are eager to work with a wide spectrum of stakeholders to exchange information and knowledge.

We are looking for partners and funding organizations to support us in conducting a new round of surveys. Please, feel free to send us your proposals.

Copyright © Xchange.org 2019