‘The Rohingya Amongst Us’: Bangladeshi Perspectives on the Rohingya Crisis Survey

“How many times they will live as nomads? Their repatriation is most needed.”

50-year-old Bangladeshi male, Nhilla

Introduction

August 25 2018 marks one year since the beginning of an aggressive Myanmar military “crackdown”; a disproportionate and indiscriminate campaign in response to coordinated attacks by Rohingya insurgents. The military’s self-described “clearance operations” drove an estimated 706,000 Rohingya Muslims en masse across the border from Myanmar into Bangladesh in what is now the fastest-growing refugee crisis in the world. [1] As demonstrated in Xchange’s Rohingya Survey 2017, [2] those who fled the most recent eruption of violence suffered considerable trauma as a result of a widespread campaign of murder, rape, and arson tantamount to crimes against humanity. [3] One year on, the result of this campaign of state-sponsored violence is the near-eradication of the Rohingya population from northern Rakhine State and an ongoing humanitarian emergency in Bangladesh, where the Rohingya population in some areas outnumber surrounding host communities by a ratio of two to one. [4]

Bangladesh has shown compassion in their openness toward the fleeing Rohingya by providing temporary shelter, keeping their borders open and, with the help of the international community, leading the humanitarian response on this issue. However, the sheer scale and speed of the most recent influx of Rohingya refugees has inevitably had an economic, social, political, environmental, and security impact on the host communities in Cox’s Bazar district, where the Rohingya refugees have almost universally settled. The district is one of the most impoverished regions of Bangladesh, already struggling to cope with extreme poverty, high population density, and the effects of regular natural disasters and climate change. [6]

Like most countries in Asia, Bangladesh is not signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, [7] meaning there are few domestic legal mechanisms for handling asylum cases. [8] As a result, the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) does not recognise the Rohingya as refugees, but rather as “Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals” (FDMN), denying the Rohingya legal refugee status and the rights associated with this. [9]

The Rohingya have been living tenuous lives within sprawling refugee camps, denied freedom of movement, access to education, livelihoods and public services. [10] Durable solutions or long-term development strategies for this protracted refugee situation for both refugees and affected local Bangladeshi communities are close to non-existent. [11] Instead, the GoB has promoted repatriation and resettlement strategies as the preferred long-term solutions. The alternative, integration, implies a sense of permanence. In light of the upcoming national elections later in 2018 where domestic issues and national interests will continue to be prioritised, the GoB seems reluctant to support integration-based policies.

Following the events of late 2017, the Bangladesh and Myanmar governments agreed in January 2018 to begin a two-year process to repatriate the more than 770,000 Rohingya Muslims who had fled Rakhine State since October 2016. [12] However, the GoB delayed repatriation amid criticism that any returns would be premature, as Rohingya refugees continue to cross the border seeking safety in Bangladesh.[13] In April 2018, a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed by UNHCR and the GoB established a framework of cooperation for the “safe, voluntary, and dignified returns of refugees in line with international standards.” [14] A tripartite repatriation deal between the governments of Bangladesh, Myanmar and UNHCR is still in progress.

Despite the restrictions placed on them, the Rohingya community in Bangladesh has shown considerable resilience. Outside the parameters of the national asylum system and beyond the confines of the camps, the Rohingya have been working informally in an effort to take their livelihoods and family finances into their own hands. [17] However, there are no government-led long-term or permanent development solutions in sight, nor any infrastructure to support the Rohingya in the long term. [18] This has significant consequences for the locals, including the burdening of public expenditure, service delivery, the labour market, and increased tension and competition between the two communities. [19]

In 2017, Xchange established a presence on the ground in Cox’s Bazar district, at the epicentre of the refugee settlement area, and has been closely monitoring developments on the ground ever since.

In our recent Rohingya surveys, Xchange documented the nature of the Rohingya population’s day-to-day lives and conditions they experience in the camps of Bangladesh. We also examined what the Rohingya understand about the details of the proposed repatriation processes, looking at what they desire and the fears they hold, both as individuals and as a community who potentially face repatriation (or refoulement) to Myanmar.

With little attention given to the real impacts on and perceptions of the host and local Bangladeshi communities, a more holistic response to this refugee crisis is therefore necessary, one that must include both the Rohingya refugees and local Bangladeshi communities as stakeholders. [20] In light of this, this survey seeks to understand the Bangladeshi host communities’ perceptions of the Rohingya refugees, including the relationship between the two communities, the most noticeable changes since the Rohingya’s most recent arrivals from 2016 onward, and their opinions about the proposed Rohingya repatriation deal and process.

Between June 30 and July 21, the Xchange team interviewed a total of 1,708 Bangladeshi locals in Teknaf and Ukhia upazilas (subdistricts) in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Of these, 1,697 surveys were considered for analysis.

During June and July 2018 we collected over 1,700 testimonies from Bangladeshi residents of Cox’s Bazar zila (district). This is what we found.

Fishermen in Baharchhara, Teknaf, Bangladesh – © Xchange Foundation 2018

Timeline of Rohingya Migration to Bangladesh

The Rohingya are a distinct Muslim ethnic group predominantly hailing from the Rakhine State (formerly known as Arakan State). Their presence in Myanmar dates back to the seventh century, with the settling of Arab Muslim traders. Despite this heritage, the Rohingya have faced decades of protracted displacement, discrimination, and restrictions on freedom of movement imposed by the Myanmar government due to their status as “illegal immigrants”. [21] Despite self-identifying as Rohingya Muslims and ‘indigenous’ peoples of Myanmar, the minority has been stripped of Myanmar citizenship under a 1982 Citizenship Law [22] which served to de facto exclude the Rohingya citizenship. This resulted in the creation of one of the world’s largest stateless populations.

1970s

In 1978, Myanmar’s army waged a brutal campaign against the Rohingya in Rakhine State, as part of “Operation Nagamin” (Dragon King), a citizenship scrutiny exercise ostensibly designed to weed out illegal immigrants. This ultimately forced more than 200,000 Rohingya out of the country into Bangladesh, which had only recently achieved independence. [25] The GoB, quickly overwhelmed by the influx, requested a repatriation agreement with Myanmar. Though Rohingya refugees were initially reluctant to return, more did so as camp conditions began to decline and food was rationed to the extent that the Rohingya faced starvation. [26] Many of the individuals expelled in 1978 and their descendants remain resident in Bangladesh to this day.

1990s

In 1991, after another wave of attacks by the military, approximately 250,000 Rohingya were forced to flee to Bangladesh. [27] The majority of those who fled in 1991-1992 were recognised prima facie as refugees due to being Muslim. However, this ended in mid-1992 when Bangladesh signed a bilateral agreement to return the Rohingya under a controversial repatriation programme. [28] The increasing number of refugees led Bangladesh to enlist the UNHCR to provide assistance to the Rohingya. [29] An MoU (Memorandum of Understanding) was subsequently drawn up between the Bangladeshi and Myanmar governments which resulted in the repatriation of the 250,000 Rohingya who were able to prove their origins in Myanmar between 1993 and 1997. UNHCR abandoned its role in the process when evidence emerged of Rohingya being coerced to return against their will, a concept known as refoulement that is against international law.

In 1993, the UNHCR once again agreed to facilitate returns after signing an MoU with the GoB. [30] However, approximately 30,000 refugees in Bangladesh were unable to give the required evidence of their previous residence in Myanmar. As a result, they were granted refugee status by UNHCR and permitted to stay in Kutupalong and Nayapara camps, the two “official” government-run camps in Cox’s Bazar District. [31]

2000s

Since 2012, the situation inside Rakhine State has been particularly volatile with widespread injury and death, the razing of villages, and mass displacement. [32] The second wave of the 2012 clashes are widely believed to have been orchestrated by security forces and political actors, as well as ethnic Rakhine Buddhist-nationalists. [33] In October and November 2016, Rohingya men, allegedly from a new insurgent group called Harakah al-Yaqin (Faith Movement), attacked three border posts in Maungdaw and Rathedaung townships in Rakhine State, killing nine police officers. The Myanmar military responded with a brutal crackdown that resulted in extensive human rights abuses and ultimately in the flight of 87,000 Rohingya to Bangladesh.

The most recent government-sanctioned crackdown on the Rohingya, starting on August 25 of 2017, was, the government claimed, a “clearance operation” in response to attacks by Al-Yakin, which had by then rebranded as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA). The group was allegedly behind coordinated attacks on 30 police posts and an army base on August 25, killing 11 members of the Myanmar security forces. [35] However, a recent report by Fortify Rights indicates that wide-ranging preparations were made by Myanmar authorities in advance of the August crackdown. [36]

International, regional, and national policy

Countries in Asia often suffer from a lack of regional planning for mass migration or large influxes of refugees and asylum seekers. Instead, human migration in the region is viewed as a domestic matter, or a bilateral issue concerning only the country of origin and the host country. In the case of the Rohingya influx into Bangladesh, government policy responses and planning have been slow and ad-hoc. The response from intergovernmental organisations such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) [37] and South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) [38] has primarily been one of non-interference. Rather, the Governments of Bangladesh and Myanmar continue to address the issue bilaterally.

Bangladesh is reluctant to introduce legislation and policies related to the definition, regulation, and protection of refugees and asylum seekers. Historically, Bangladesh’s response to the influx of Rohingya refugees has been to enable humanitarian relief and implement push-back policies and repatriation. [41] The majority of protection-related assistance, including registration and needs assessments, has been provided by multilateral organisations, such as the UNHCR and IOM, and international aid organisations.

In an attempt to curb the integration of Rohingya into Bangladeshi society, the GoB has implemented multiple restrictions on the community. For example, a 2014 law forbids registrars from marrying Bangladeshi-nationals and Rohingya, in a bid to limit the number of Rohingya able to obtain Bangladeshi citizenship; anyone found to have married a Rohingya can face seven years in prison. [42] In addition to this, the GoB upholds that children born in Bangladesh do not have a right to Bangladeshi citizenship but are registered as ”Citizens of Myanmar”. [43] The limited education available in the camps is taught in English and Burmese, rather than Bengali. [44] Despite the government trying to limit Rohingya integration into Bangladeshi society, as highlighted in this report, the reality on the ground is quite different.

Thus, the lack of legal and policy framework pertaining to refugee protection in Bangladesh leaves the Rohingya vulnerable to exploitation and abuse in their host environment. Their irregular status and restricted mobility, coupled with their limited access to livelihoods and education, forces them to be almost entirely reliant on international aid. This allows the GoB to distance themselves further from responsibility and drives the Rohingya underground in search of some normality. The result is an extremely vulnerable Rohingya population, both inside and outside the camps, who face threats of corruption, exploitation, and crime at the hands of opportunist locals. [45]

Tuktuks in Baharchhara, Teknaf, Bangladesh – © Xchange Foundation 2018

Bangladesh: a reluctant host country

Cox’s Bazar District: the epicentre of displaced Rohingya

Bangladesh currently hosts the second largest number of refugees in South and Southeast Asia, due to the recent Rohingya influx from Myanmar. [46] The majority of Rohingya refugees reside in Cox’s Bazar District, a coastal region of south-eastern Bangladesh. The area is a popular destination for domestic tourism and its 120-kilometre sandy coastline is home to the longest natural sea beach in the world. [47] Cox’s Bazar shares a 62-kilometre border with Myanmar, separated by the Naf River, an obstacle that many Rohingya refugees had to navigate in their exodus from Myanmar.

Cox’s Bazar has a population of 2,290,000 and is one of Bangladesh’s poorest districts. [48] Even before the influx of Rohingya refugees, one in five households in Cox’s Bazar experienced poor food consumption levels well above the national average. On average, 33% lived below the poverty line, and 17% below the extreme poverty line. [49] The country is also subject to serious climate changes and environmental hazards – it is hit by approximately 40% of the world’s total storm surges [50] which regularly undermine the local populations’ resilience and livelihoods. [51]

Bangladesh is on track to graduate from the UN’s Least-Developed Country list by 2024 due to sustained economic growth and remarkable success in reducing poverty in recent years. [52] However, high poverty rates still prevail with approximately 22 million people living below the poverty line and an ever-increasing population density. [53] Bangladesh is currently ranked at 139 (of 188) on the Human Development Index. [54]

The recent influx of Rohingya refugees and haphazard construction of sprawling camps in one of the poorest areas of the country has understandably roused local concerns: both communities are competing for resources and there has been widespread destruction of forests and agricultural land, and a related surge in inflation for everything from food to housing prices. [55]

The GoB has, historically, tried to separate refugees from the local Bangladeshi population by containing the Rohingya population in official camps. By attempting to prevent the Rohingya self-settling, the GoB can more easily manage and monitor the population, with a view to facilitating repatriation. [56] However, to some extent, the protracted displacement of the Rohingya has resulted in their de facto integration in Bangladesh, particularly for those settled outside of the camps from previous waves of migration. Integration is made easier by the Rohingya and Bangladeshi communities’ shared faith and cultural and linguistic characteristics. [57]

In Cox’s Bazar, there are only two officially-recognised “registered” camps, Kutupalong and Nayapara, which sit side by side the many spontaneous “makeshift settlements” scattered across the district. As the recent crisis quickly escalated and the mass exodus of the Rohingya to Bangladesh began, the GoB made available 500 hectares of forest land; [58] 4,800 acres of which sits in close proximity to Kutupalong Camp. This expansion site together with the original camp has since become the Kutupalong-Balukhali ”mega-camp”, the world’s largest refugee camp, hosting more than 600,000 people. [59] The site has grown from 146ha to 1,365ha (a total growth rate of 835%) in response to the rapid population growth.

In the Kutupalong-Balukhali mega-camp there is, on average, just 10.7 square meters of usable space per person compared to the recommended international standard of 45 square metres per person. [60] Such overpopulation within the camp increases the vulnerability of its inhabitants and also that of neighbouring Bangladeshi villages. Mismanagement of WASH facilities and poor camp planning have led to contamination of local agricultural land and drinking water sources, as well as increased likelihood of fires. This poses major concerns for the health and safety of those living in the camp’s vicinity. One existing major concern is the rise in the number of communicable diseases present in the camp. Instances of sexual and gender-based violence (S/GBV) are on the rise, as are inter- and intra-community tensions. [61] In addition to this, such swift expansion has resulted in rapid degradation of forested land, causing ecological problems and disturbing local communities and wildlife habitats. [62] The multi-hazard environment is subject to regular extreme weather events, meaning that approximately 215,000 refugees in Cox’s Bazar are in danger of landslides and flooding, yet as of June 2018, only 19,500 have been relocated from sites deemed to have the highest risk [63]

In May 2015, the GoB suggested the relocation of Rohingya refugees to Hatiya Island in the Bay of Bengal, to reduce disruption to host communities and the tourism sector in Cox’s Bazar. [64] Similar plans emerged in 2017, with an announced intention to move refugees to Thengar Char, a low-lying “uninhabitable” island. [65] However, with the current restrictions on mobility, this plan could be tantamount to relocating Rohingya refugees to an offshore detention camp. It offers no durable solutions to the crisis.

Local boats (nowka) – © Xchange Foundation 2018

Methodology & Research Implementation

The findings presented in this report are based on primary data collected in Cox’s Bazar district, Bangladesh over a period of three weeks, from June 30 to July 21, 2018. The research team employed a mixed-method approach where in-depth individual interviews supplemented a large-scale cross-sectional survey conducted with around 1,700 local Bangladeshis across the southern part of Cox’s Bazar district where the majority of the Rohingya refugee population resides.

Objective & Research Questions

The survey aims to understand the local Bangladeshi community’s perceptions of and relationship with Rohingya refugees, the most noticeable changes in their community since the recent Rohingya arrivals, and their opinions about the proposed Rohingya repatriation deal and process.

The following research questions were formed to address the research objective:

What are the perceptions of the local Bangladeshi communities toward the Rohingya refugee population?

- To what extent do the local Bangladeshi communities believe they have been welcoming to the Rohingya?

- What effects have local Bangladeshis noticed on their communities since the recent Rohingya arrivals (since 2016)?

- What are the locals’ opinions and beliefs on the Rohingya repatriation deal?

A. Survey

Sampling-Planning

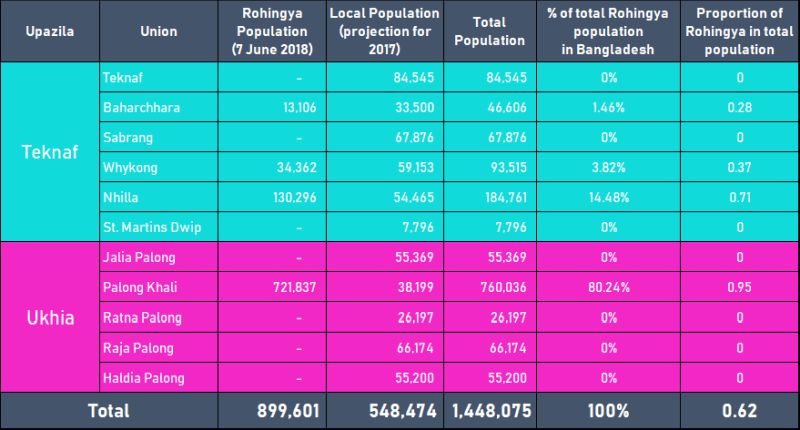

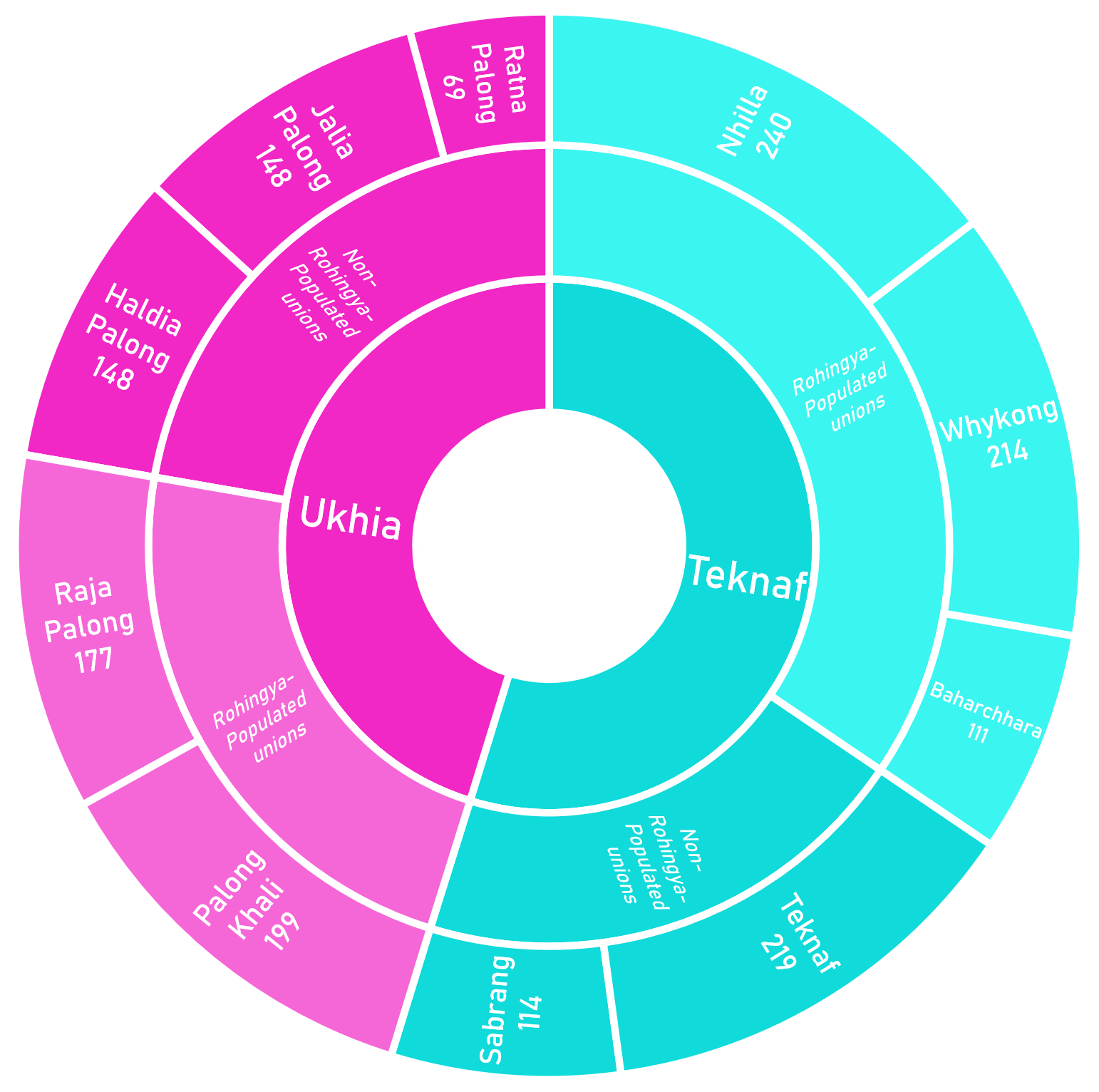

The cross-sectional survey took place in two of the eight upazilas that make up Cox’s Bazar zila, namely Teknaf and Ukhia. [66] The target population was estimated to be 229,380 adult Bangladeshis living in a union within Teknaf or Ukhia (126,563 and 102,817 adult Bangladeshis, respectively). [67]

The researchers employed a disproportionate stratified random sampling [68] procedure on the individual level. [69] The stratification process was conducted on the basis of union of residence and sex, based on population figure estimates [70] for the two focus upazilas, Teknaf and Ukhia. The two upazilas are comprised of six and five sub-regions or unions, respectively. In detail: [71]

Unions in Ukhia and Teknaf upazilas. [72]

Of the above-listed unions, only Whykong, Baharchhara, Nhilla, Palong Khali, and Raja Palong, where refugee camps and makeshift settlements are located, have significant and established new Rohingya populations. Unsurprisingly, unions with significant Rohingya populations have smaller local Bangladeshi populations than areas with fewer or without Rohingya. [73]

The researchers considered it to be important that the unions with significant Rohingya populations are represented more than unions without in the sample as the locals living closer to the Rohingya community might have a better understanding of the situation than those living in other unions. [74] The target number of surveys was 1,700. Using design weights, different sampling fractions for each stratum were calculated to identify sub-samples (samples for each union). After the total number of individuals to be surveyed in each union was identified, the researchers used the sex ratio of each union to identify the corresponding number of men and women to be interviewed in each union. Finally, randomisation was ensured during data collection as the enumerators selected individuals to be interviewed without order in various villages and mauzas in the respective unions.

Fieldwork-Data Collection

The fieldwork took place over a period of three weeks, from June 30 to July 21, 2018. The data collection team was comprised of four (two male and two female) local Bangladeshi residents of the two upazilas. The enumerators were extensively trained both remotely and with the help of a local facilitator. The local facilitator was an experienced Rohingya enumerator, who could give important insights from the Rohingya perspective to minimise the potential for the enumerators imparting any bias they may have harboured.

The survey was conducted with the use of a questionnaire distributed through an online data collection application. All interviews were conducted in Bengali to minimise response bias. The questionnaire included 44 main questions and several sub-questions and was translated into Bengali by the enumerators and the facilitator and imported onto the online platform.

The questionnaire [75] included close-ended (yes/no), multiple- or single-choice, Likert-scale, [76] and open-ended questions. The answers to the open-ended questions were translated by the enumerators from Bengali to English on the spot. All quantitative data collected were translated back to English prior to analysis.

A pilot test (22 questionnaires) of the research instrument in Baharchhara and Raja Palong unions was conducted two days prior to the official data collection period. Minor changes, such as translation corrections, were made to the questionnaire to improve the respondents’ understanding and minimise potential response bias.

Every day, the enumerators were assigned a number of surveys to conduct at a specific location (including unions, villages and mauzas in that union). In total, fieldwork took place in more than 71 (up to 97) villages across the two upazilas, [77] more than 50 in Teknaf and more than 21 in Ukhia. A total of 1,708 questionnaires were completed, of which 1,697 were analysed; 893 with men and 804 with women. [78]

The sample of 1,697 respondents can be considered broadly representative of the total adult Bangladeshi population residing in Ukhia and Teknaf upazilas. On a 95% confidence level, the margin of sampling error stands at 2.37.

All surveys were conducted in person after respondents were informed about the survey’s objectives. Respondents were provided with anonymity and verbal consent was ensured before proceeding with each survey. The male enumerators were instructed to interview male respondents and female enumerators interviewed female respondents where possible, except when logistical complications required otherwise.

Limitations

Sampling

The most recent Population and Housing Census of Bangladesh took place in 2011, meaning that the research team had to use rough estimations to identify the current (2017-2018) population in the two upazilas of interest to identify the subsamples. Many of the targeted locations (villages) were small and online maps were either inconsistent, outdated, or did not provide their exact names and/or coordinates. This required the researchers to rely on various online sources including articles and reports, as well as the enumerators’ local knowledge. Consequently, some villages may have been unintentionally excluded.

Data Collection

The data collection was conducted during monsoon season, during which time certain villages were not accessible due to flooding. This resulted in an unintentional interruption to the randomness of the sample. For instance, St. Martins Dwip, an island union in the south of the country, was inaccessible on the planned dates for data collection and therefore excluded from the sample. However, the target areas were re-stratified two days before data collection was completed and respondents from other unions compensated correspondingly for the data loss. The results of this report are therefore generalisable to the whole of the Ukhia and Teknaf upazilas, excluding St. Martins Dwip.

Analysis

All enumerators were highly educated, however, none of them were native English speakers. As some responses were translated from Bengali to English by each enumerator on the spot, this might have resulted in misinterpretations and/or have negatively influenced the accuracy of some responses. [79]

The results yielded regarding the respondents’ views of the Rohingya should be interpreted with caution, as we cannot rule out the possibility of some sort of bias. For instance, in the question regarding access to public facilities by Rohingya, there is a possibility of extreme response bias. However, overall, these results were included in the report as they were consistent with anecdotal evidence, geographic details about certain places which came to the researchers’ knowledge at a later stage, and additionally supported by the in-depth interviews.

B. In-depth Interviews

To gain better insight into the local Bangladeshi perceptions of the Rohingya the research team conducted a small number of in-depth interviews (four with men and two with women) with key stakeholders, employees of NGOs or governmental bodies, in three unions: Sabrang, Baharchhara, and Nhilla. All interviews were conducted by a female interviewer (one of the enumerators).

The in-depth interviews were held during the third week of survey data collection with the use of an in-depth interview guide which was developed on the basis of the survey’s preliminary findings from the data collected during the first week. [80] The length of the interviews ranged from 20 to 30 minutes.

Before each interview took place, the interviewer explained its purpose and the concept of confidentiality. After she had ensured that participation was entirely voluntary and provided the interviewees with the right to withdraw from the interview at any time, written informed consent was collected.

The interviews were held in quiet and private places and recorded with a mobile phone. After the interviews were finished, the interviewer transcribed them and transferred them to the research team for qualitative analysis.

Tuk tuk and cattle, Bangladesh – © MOAS.eu/Dale Gillett 2018

Key Findings

Demographics-Sample Description

Between June 30 and July 20, the Xchange team interviewed a total of 1,708 Bangladeshi locals in Teknaf and Ukhia upazilas in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. 1,697 of these surveys were considered for analysis.

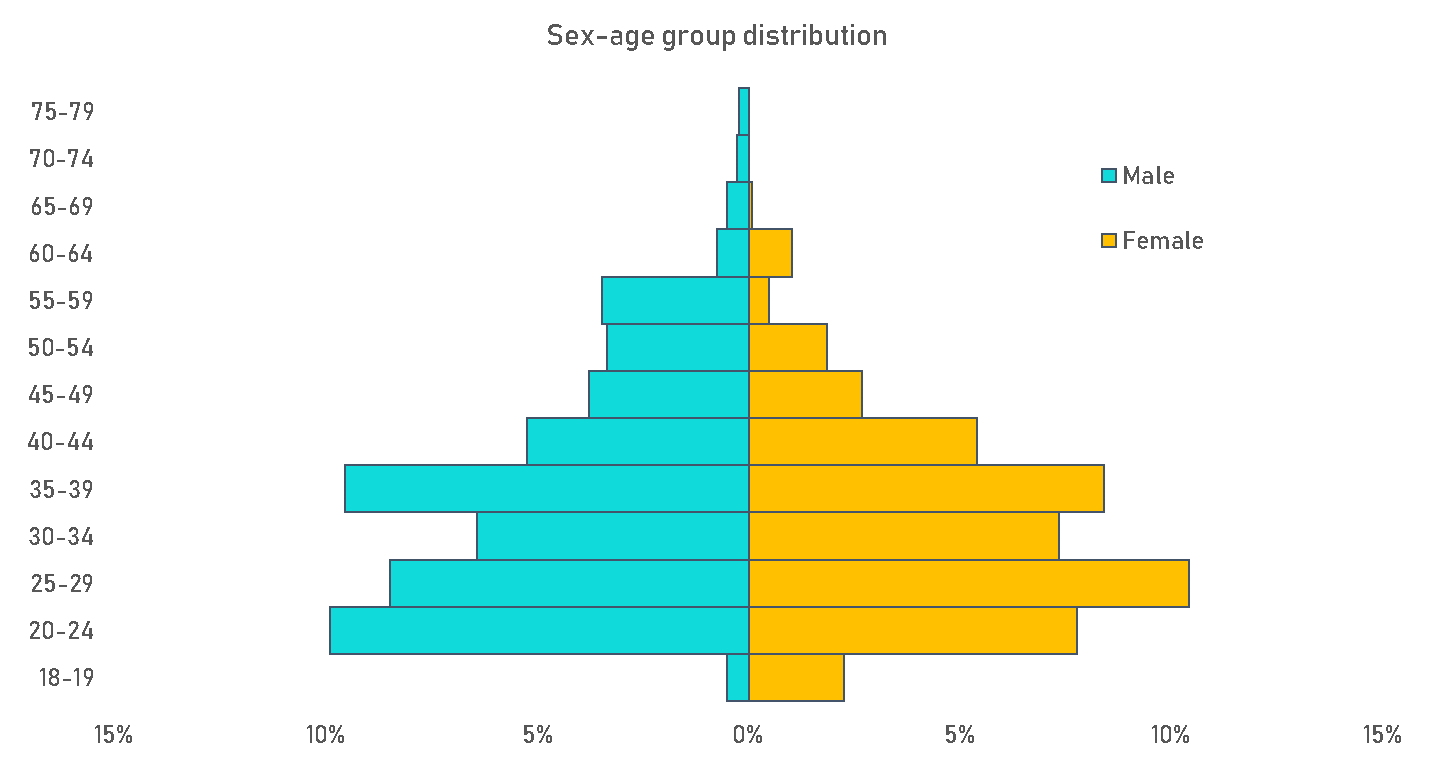

Sex: The sample consisted of 893 (53%) male and 804 (47%) female Bangladeshis.

Age: All respondents were adults. Their ages ranged from 18 to 76 years, with a median of 32. More than half the sample (52%) was below the age of 35, with one fifth (20%) below the age of 25. The largest age group, or mode, (19% of the sample) was the 25-29-year-olds. By sex, most male respondents (19%) were between 20 and 24, and most female respondents (22%) between 25 and 29 years of age. No women above the age of 65 were interviewed.

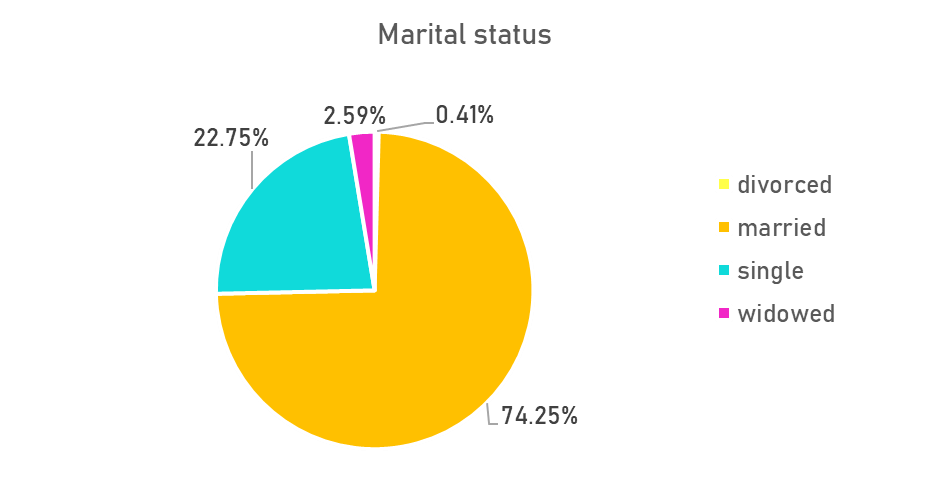

Marital Status: The majority of respondents, 1,260 (74%), were married; 386 (23%) were single; 44 (3%) were widowed, and seven (0.4%) were divorced at the time of the survey. The percentage of ever-married respondents was 77% (87% of all females and 69% of all males).

Relatively more female respondents were married than male respondents (80% and 69%, respectively); more male respondents were single than female respondents (31% and 13%, respectively); no male respondents were divorced and only one was widowed.

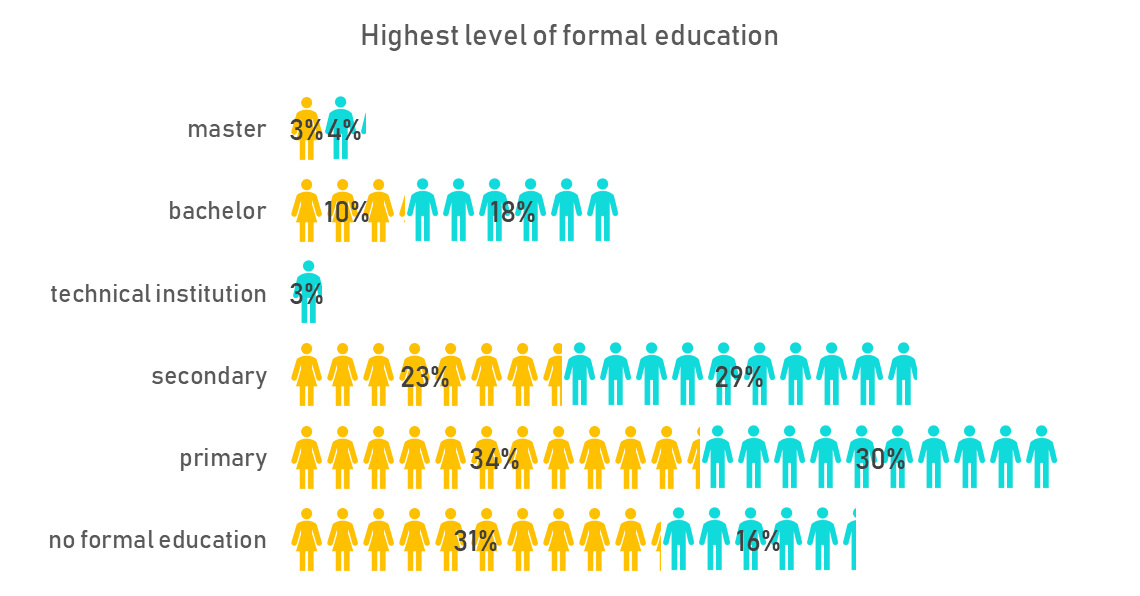

Education: Almost one quarter (23%) of all respondents did not receive any formal education, one in three (32%) only received primary education, while the remaining 45% received at least secondary education (including 17% who progressed to tertiary education). This means that the majority (77%) had attained some level of formal education, 58% of whom received at least secondary.

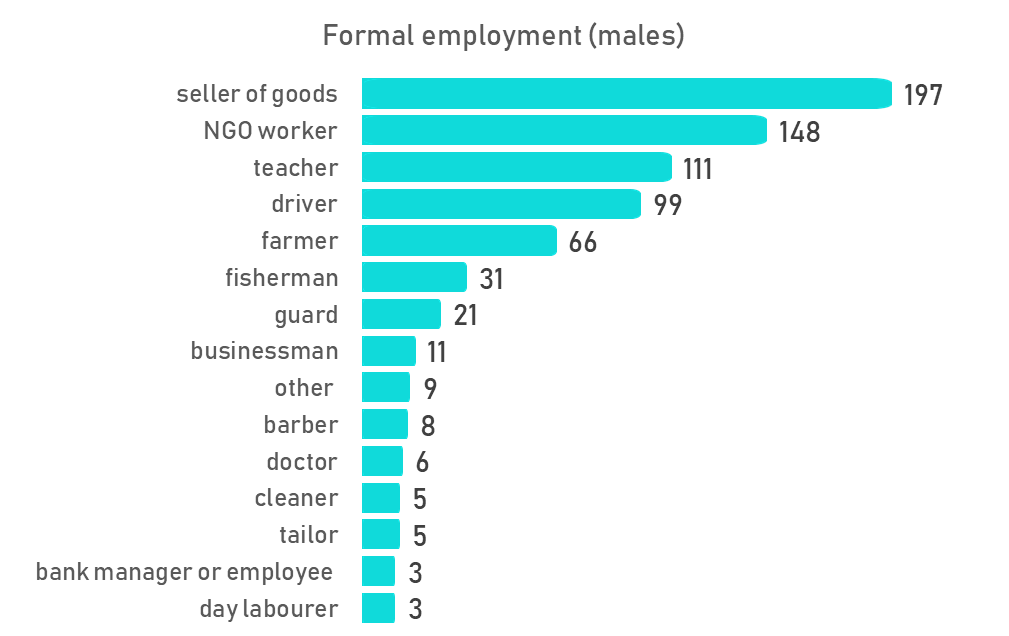

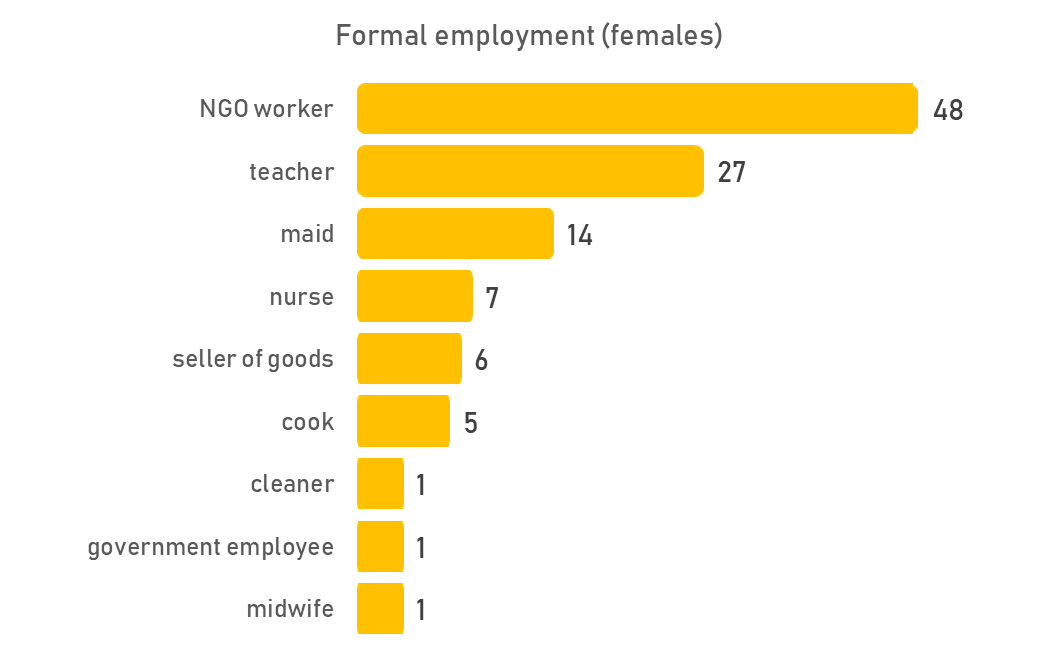

Employment: Nearly half (836 or 49%) of all respondents were formally employed at the time of the survey, 87% of whom were male. The remaining 51% were not engaged in any formal economic activity.

By sex, 81% (726) of men were employed compared to just 14% (110) of women. In all age groups below 35-39, there were more unemployed respondents than employed. Relatively more respondents with higher levels of education (83%, 80% and 87% technical institution, Bachelor, and Master graduates, respectively) were engaged in formal employment than those with lower-level or no formal education (53% and 39% of secondary and primary education graduates, respectively, and 32% of those without formal education).

The majority of the formally employed respondents most frequently worked as shop keepers selling goods of various sorts (24%) or at a local or international NGO (23%). The top three occupations for formally employed female Bangladeshis were: NGO job (48 or 44%), teacher (27 or 25%), and maid (14 or 13%), while the top three for the formally employed male Bangladeshis were selling goods (197 or 27%), NGO job (148 or 20%), and teacher (111 or 15%).

Residence: The respondents were residents of either Teknaf (956 or 56%) or Ukhia (741 or 44%) upazilas. The two upazilas are further divided into unions, some of which have significant Rohingya populations, as explained in the Methodology & Research Implementation section.

55% of respondents (941) resided in Rohingya-populated unions: in Baharchhara, Whykong, and Nhilla in Teknaf upazila (565 or 59% of all Teknaf-residing respondents) and; Palong Khali and Raja Palong [81] in Ukhia upazila (376 or 51% of all Ukhia-residing respondents).

The remaining 45% of respondents (756) resided in unions without a significant Rohingya presence: Teknaf and Sabrang in Teknaf upazila (391 or 41% of Teknaf-residing respondents) and; Haldia Palong, Jalia Palong, and Ratna Palong in Ukhia upazila (365 or 49% of Ukhia-residing respondents).

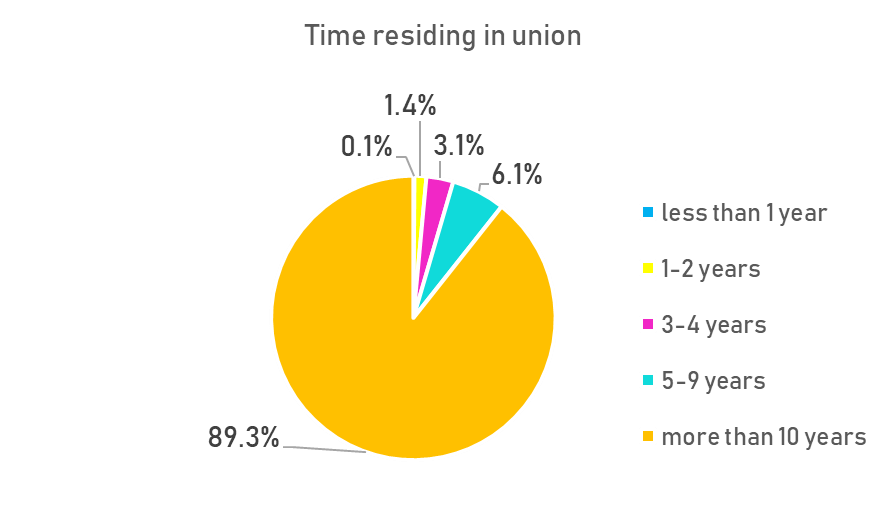

Time residing in union: The vast majority of residents of the two upazilas (1,620 or 95%) had been living in their union for more than five years, 94% (1,516) of whom had been living in their unions for more than a decade. The majority of respondents had therefore been present for more than one inflow of Rohingya refugees. Only 25 individuals (or fewer than 1.5% of the sample) had moved to their union after 2015.

Disaggregated by upazila, 94% of residents of Teknaf had been there for more than a decade, with only 1% having arrived in the last four years, compared to 83% and 8% of residents of Ukhia, respectively.

Household size: The size of household in Teknaf and Ukhia ranged from one to 12 people. [82] The median number of people the respondents shared their household with was four (median household size is five). However, most respondents (543) lived in the same household with four others (mode household size is five).

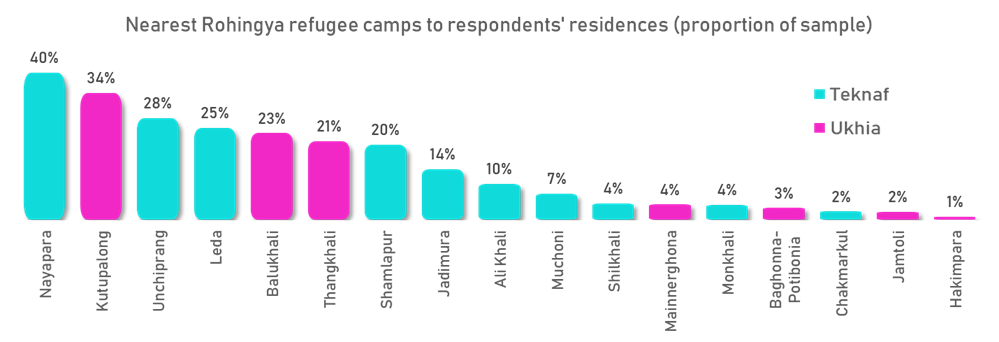

Closest Rohingya settlements: Respondents were asked to locate the three closest either registered or unregistered Rohingya settlements to their residence.

- Teknaf: 71% of locals live near Nayapara, 49% near Unchiprang, and 44% near Leda.

- Ukhia: 79% of locals live near Kutupalong, 54% near Balukhali, and 46% near Thangkhali.

Interestingly, 30 male respondents, all from Teknaf union in Teknaf upazila (14% of all respondents, residents of Teknaf union, or 26% of all male respondents, residents of Teknaf union) did not know which the closest Rohingya camps to their residence were. This could be because many villages in Teknaf union are located in the vast forest area of this largest-by-area union of both upazilas.

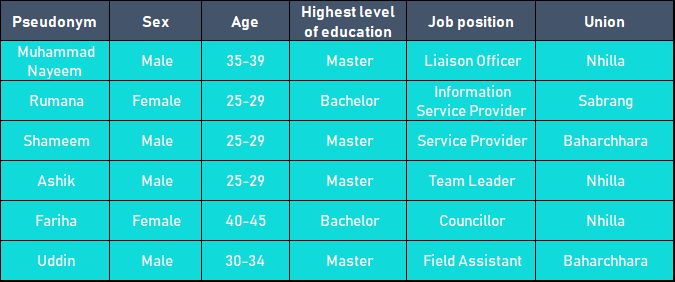

In-depth interviews sample

The sample of the in-depth interviews consisted of six local Bangladeshis: four men and two women. Their median age was 29 and all had a strong educational background. The men were masters graduates and the women were bachelors graduates.

With regards to their occupation, all were working for a national or international NGO or in a governmental institution.

All interviewees were residents of Teknaf upazila. More specifically, three lived in Nhilla, two in Baharchhara, and one in Sabrang, and they all had been living in their region since birth. Three were married, two of whom had children. Three were single without children.

Livelihoods, Education, and Safety Concerns

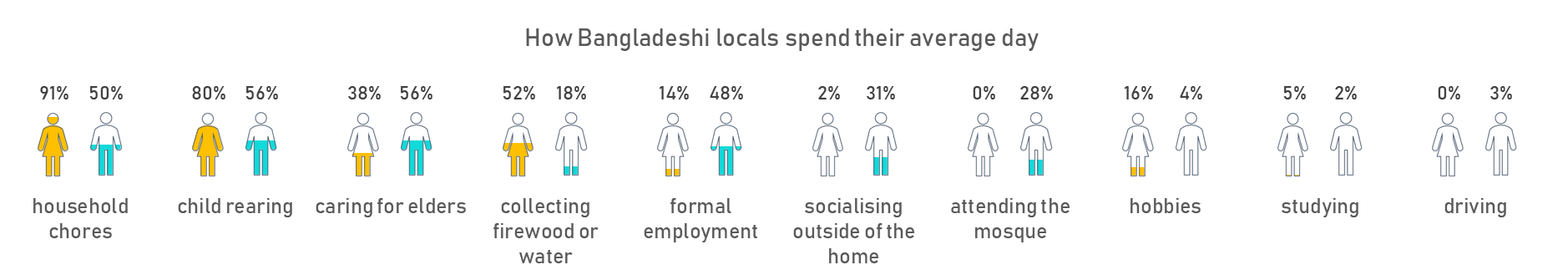

Daily Activities: Most respondents spent time engaged in household or family activities: 70% of respondents mentioned spending their time on household chores, such as cleaning and cooking, 68% took care of their children’s needs, and 48% cared for the elders of their household. However, many of the respondents’ daily activities were gendered. [83] Some categories were exclusive to men, such as attending the mosque, driving, farming or land cultivation, and fishing.

“I live in Sabrang. Most of the people in this union are immigrants. Some are fishermen, some are drivers. Very few people do government and NGO jobs. People use tuk tuks here to travel. Most of the houses in this area are semi-buildings, with some made by bamboo and babbitt. The crime rate is high here, as this area is famous for drug trafficking.”

Rumana, Information Service Provider, Sabrang

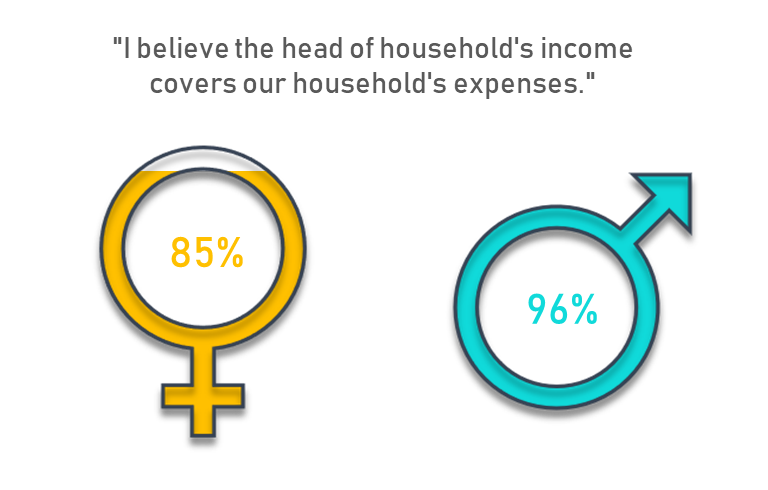

Household Income: 91% of respondents supported the statement that their head of household’s income covers their household’s expenses. Here, relatively more male respondents (96%) agreed with the statement than female respondents (85%). By upazila, relatively more residents of Teknaf (96%) agreed than residents of Ukhia (84%).

The remaining 9% reported either relying on loans, informal employment (such as gardening, fishing, driving, working as servants, or opportunistic day labour) or other family members.

“I have to maintain my family’s expenses by my teaching profession, but the prices of daily necessary goods are increasing day by day. It’s quite hard to maintain my family’s expenses.”

50-year-old Bangladeshi male, Nhilla.

Local Community

We asked the respondents whether they felt satisfied with the availability of public facilities (e.g. schools, hospitals, mosques, community centres), and the number of job and educational opportunities in their community.

Public Facilities: Approximately 84% of respondents believed that there were enough public facilities in their community at the time of the survey. Not as many female respondents were as satisfied as male respondents (73% and 95%, respectively).

In the unions with a significant Rohingya presence, 92% of respondents were positive that there were enough public facilities in their community unlike 78% of those from a union without a significant Rohingya presence. [85]

Of the remaining 16% who felt there were not enough public facilities locally, most stressed that there was a need for more governmental hospitals, educational institutions such as high schools and colleges, skilled teachers and doctors, as well as proper road planning and construction. [85]

“We don’t have enough educational institutions. We have to go to [the city of] Cox’s Bazar for a critical medical case. We highly need a government hospital in our local community area. We also need safe public transport.”

50-year-old Bangladeshi male, Nhilla

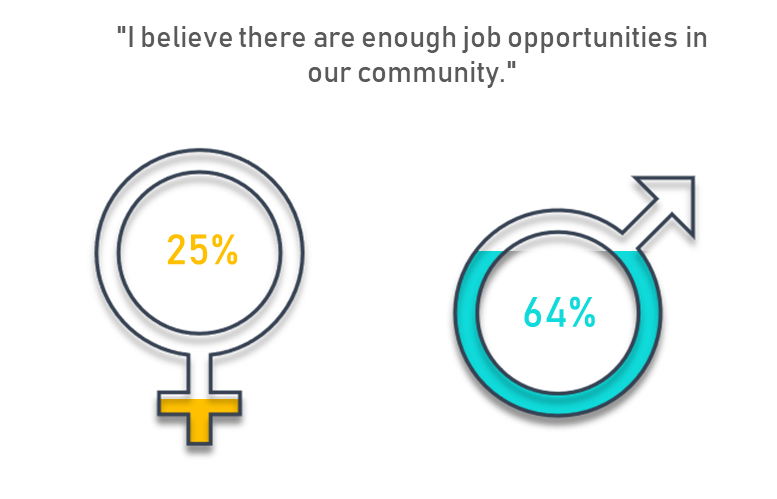

Job Opportunities: Fewer than half of the local Bangladeshis (45%) believed there were enough job opportunities in their communities, the majority of whom were men. By sex, only one in four (25%) females believed that there were enough job opportunities in their community, compared to 64% of males.

More than half of the residents of Ukhia (393 or 53%) were satisfied with the number of job opportunities in their community compared to only two in five (378 or 40%) residents of Teknaf.

49% of respondents in Rohingya-populated unions were satisfied with the number of job opportunities in their community, compared to 40% of those in unions without a significant Rohingya presence. [86] These results could indicate a growth in job opportunities for the locals since the Rohingya arrived in those areas, as some respondents indicated:

“Owing to the Rohingya, we get many opportunities [nowadays]. So, they will remain in our country.”

23-year-old Bangladeshi male driver, Teknaf

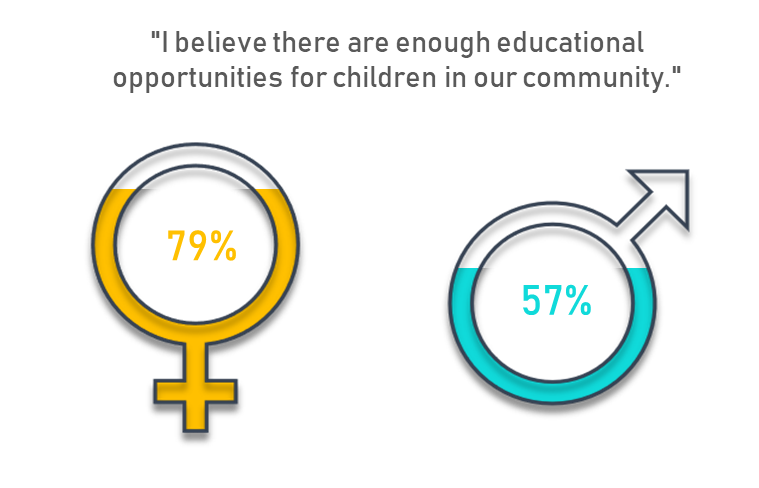

Educational Opportunities: Approximately 68% of respondents believed there were enough educational opportunities for the children in their community. However, relatively fewer males stated this than females (57% of all male compared to 79% of all female respondents). [87]

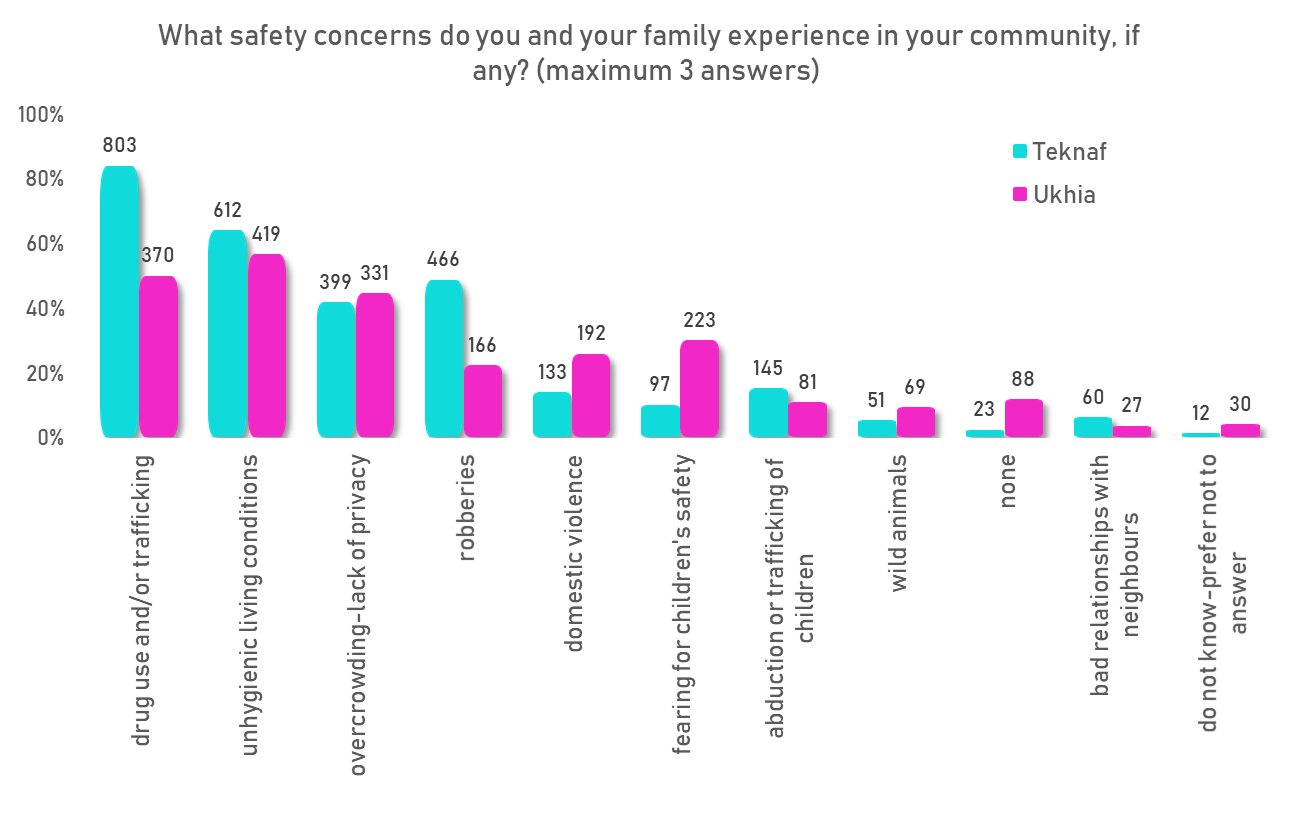

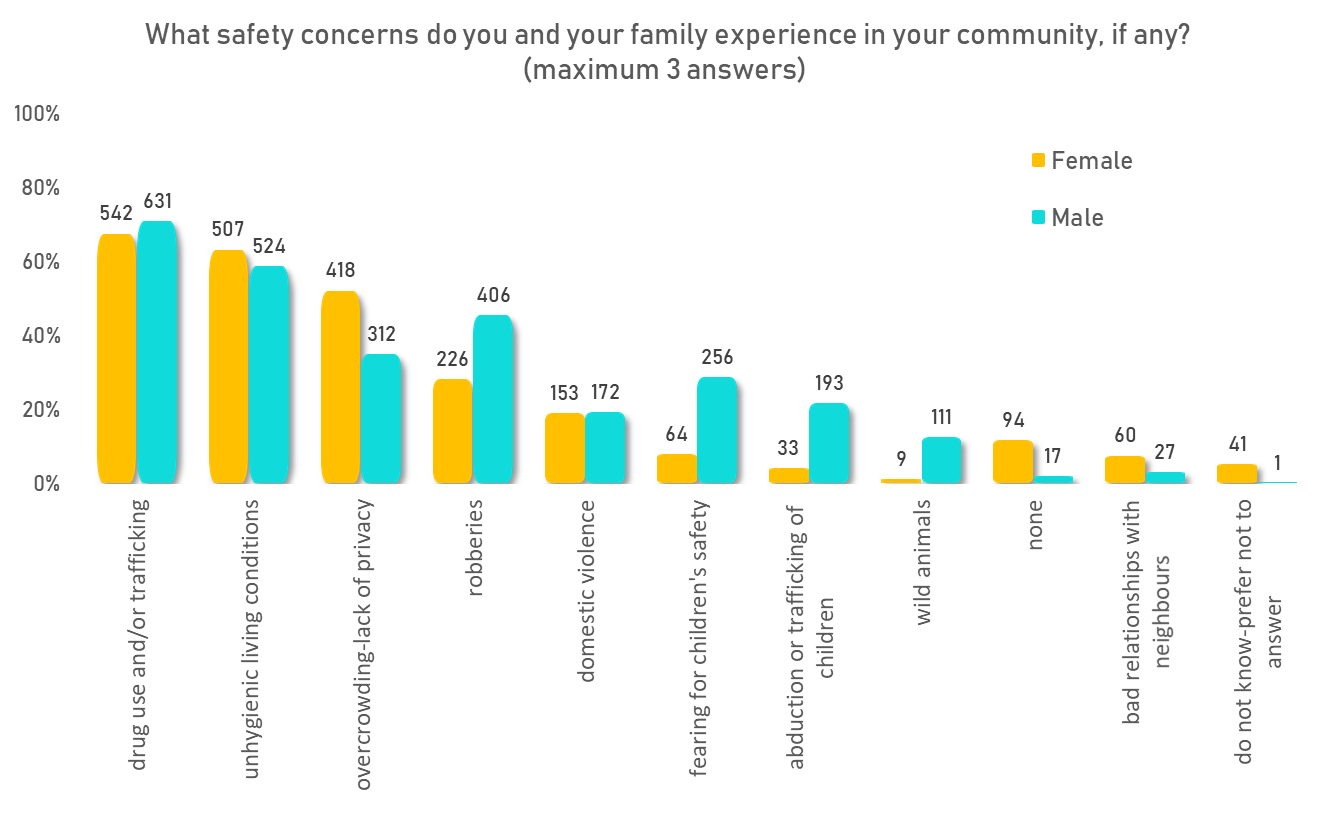

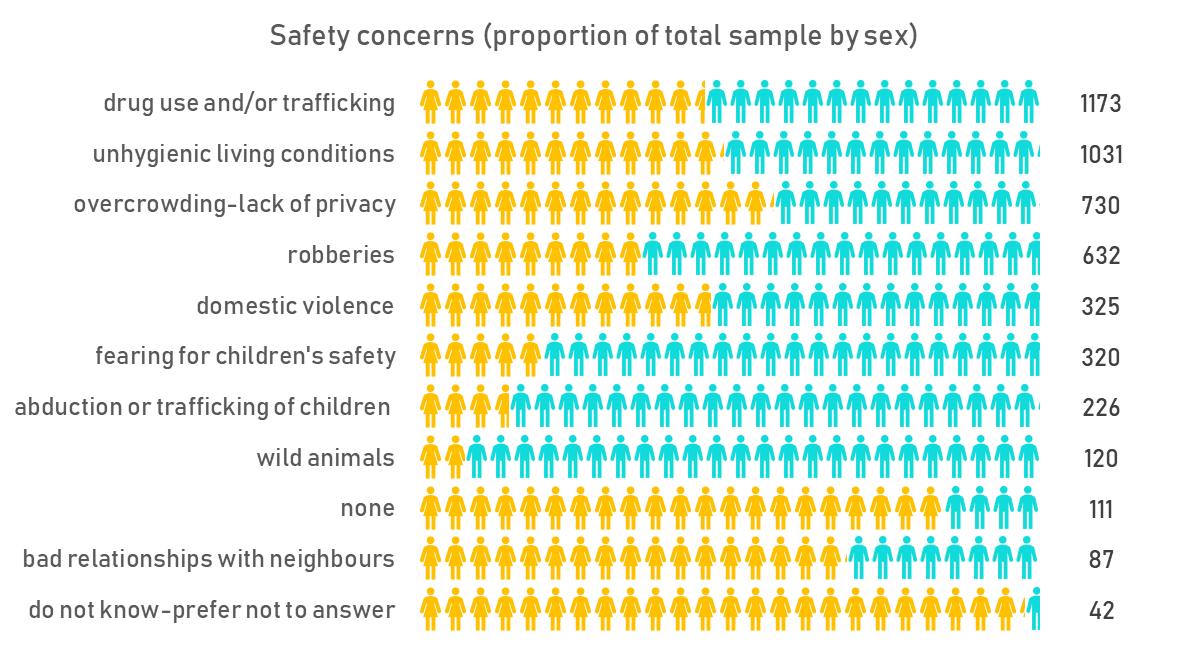

Perceptions of Safety: 93% of respondents had at least one safety concern. The two biggest safety concerns expressed by respondents were drug use and/or trafficking (69%) and unhygienic conditions (61%). These fears were higher in unions with significant Rohingya populations (74% and 69%, for drug use and/or trafficking and unhygienic conditions, respectively) than in those without (63% and 51%, respectively). In the unions with significant Rohingya populations, the third-most popular response was robberies (45%), while in the unions without, overcrowding-lack of privacy (46%).

Notably, nearly half (49%) of all residents of Teknaf feared robbery, more than double the corresponding proportion for Ukhia (22%). The majority of respondents from each union in Ukhia feared unhygienic conditions (56% in total), whereas the majority of respondents from each union in Teknaf feared drug use and/or trafficking (85% in total). This finding shows a larger dispersal of responses in Ukhia, as shown in the graph above and may reflect the different concerns the local Bangladeshis have in their unions in relation to the Rohingya settlements.

Only 111 respondents (7%) did not have any safety concerns, 85% of whom were female and only 15% were male. Moreover, only 2% of all respondents from Teknaf did not have any safety concerns compared to 12% of all respondents from Ukhia, which could represent the different levels of hardship and dangers present in the camps.

Notably, 325 individuals (19% of all males and 19% of all females; 19% total) were concerned about domestic violence. [88] Anecdotal evidence suggests that men can be abusive within the household towards women but also towards each other through intergenerational violence and it is an equally important concern for both males and females.

Of the 320 individuals (19%) concerned about their children’s safety, eight in ten were male. [89] More people living in Ukhia (three in ten or 30%) feared for their children than in Teknaf (one in ten or 10%).

Of the 226 individuals (13%) who reported being concerned about trafficking or abduction of children, 85% were male. This could be supported by the fact that men, culturally, are more socially active outside the home and therefore have more knowledge on the matter.

Relatively more people were concerned about trafficking or abduction of children in unions without a significant Rohingya presence than in those with (21% compared to only 7%, respectively), which could indicate that either those who live closer to the Rohingya have more pressing concerns, or that trafficking in minors occurs just as often – or more often – in areas with fewer Rohingya despite what the majority of respondents and participants indicated.

Local fishing boats (nowka) – © MOAS.eu/Dale Gillett 2018

Relationship with the Rohingya

Interaction with the Rohingya: The Rohingya and Bangladeshi communities have many opportunities to interact as refugee camps are often in close proximity to local villages and many Rohingya also live within Bangladeshi host communities.

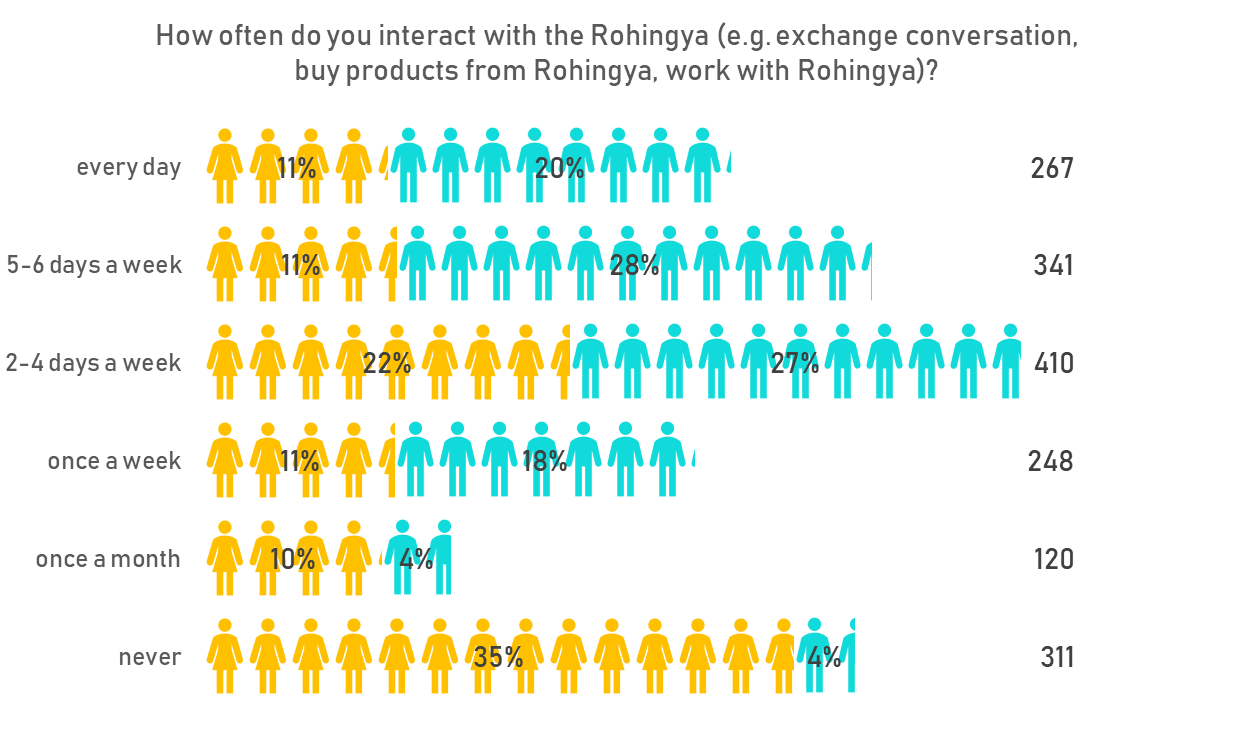

Interaction with the Rohingya was frequent for the locals in both Teknaf and Ukhia: three in four respondents (75%) interacted with the Rohingya at least once a week; 15% once a week; 24% from two to four days a week; 36% more than five days a week, and 16% every day.

Of those who interacted with a Rohingya more than five days a week, 71% were males, whereas 70% of those who interacted with them once a month were females. This could be due to cultural gender norms, meaning that women socialise less outside the home than men.

“We live near the Myanmar border. Every day we communicate with Rohingya in Teknaf union in many ways.”

40-year-old Bangladeshi male, Teknaf

This gender divide becomes clearer when considering that of the substantial 18% who had never interacted with a Rohingya, 90% were female. Notably, one in three Bangladeshi women, residents of either Teknaf or Ukhia had never interacted with the Rohingya.

Proximity to the Rohingya refugee camps is likely to play a positive role in the frequency of interactions, as three in ten (29%) residents of unions without significant Rohingya populations never met a Rohingya compared to one in ten (10%) of those living in Rohingya-populated unions.

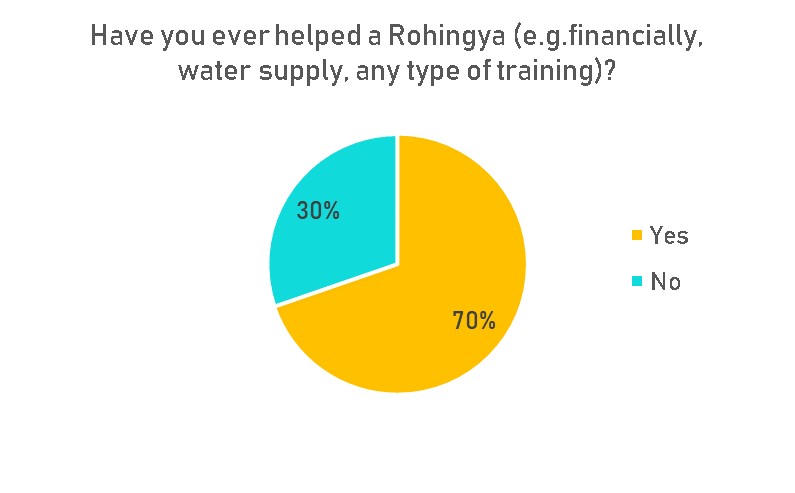

Helping the Rohingya: Seven in ten residents (70%) of local Bangladeshi communities reported having ever-helped a Rohingya. Relatively more males (81%) than females (57%) reportedly gave their assistance which could be an outcome of gender norms in Bangladeshi society, as indicated above.

In Teknaf, 86% of residents had assisted the Rohingya, compared to fewer than half (49%) of residents of Ukhia. The higher proportion of positive responses in Teknaf is likely to be linked to Teknaf’s proximity to Myanmar’s Rakhine State and the pathway for Rohingya leaving Myanmar. The majority of the Rohingya living in Bangladesh, even those residing in more northern upazilas, have once crossed through Teknaf before settling in a refugee camp elsewhere.

Moreover, 77% of respondents from unions with Rohingya refugee camps ever-helped a Rohingya, compared to a lower 61% of the remaining unions, possibly indicating that the closer to the Rohingya, the more frequent the interactions between the two communities.

“It is a matter of sorrow that they are helpless. We should help them.”

35-year-old Bangladeshi male, Teknaf

Locals showed great empathy when explaining how they had been providing charity and humanitarian assistance over time:

“After seeing the misery, sympathy was felt in everyone’s [locals’] heart for them [Rohingya]. Local people were concerned about how to give the Rohingya shelter, how to give them medical support, how to give them food.”

Ashik, Team Leader, Nhilla

“Their condition was deplorable. Most of them were women and children. They had no food, clothes, or shelter. They roamed like refugees. Their face was “horror of death”. I was shocked to see this disaster in humanity. I saw a Rohingya girl who was just eating rice with water. This scene made me cry. Then I decided to build a volunteer team; I received money from my friends, relatives, and local people to help the Rohingya. I campaigned for the Rohingya on Facebook. Then different people started to help in different ways. All of our teams made arrangements of food for 700 people. We provided biscuits for 1,000 Rohingya children and clothes for 700 women and children.”

Uddin, Field Assistant, Baharchhara

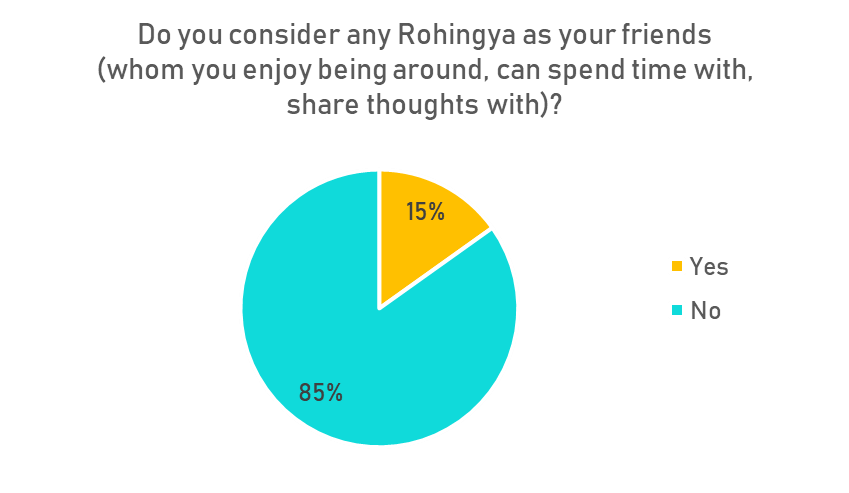

Friendship: Despite the large number of Bangladeshis who interact with the Rohingya regularly, only 15% of adult Bangladeshi residents of Teknaf and Ukhia, the vast majority of whom are men (91%), had at least one Rohingya friend, i.e. a person whom they enjoy being around, spend time with, and share thoughts with. This is in line with Xchange’s Rohingya Repatriation Survey findings, where 16% of the Rohingya were found to consider at least one Bangladeshi their friend.

Relatively more male Bangladeshis considered a Rohingya to be their friend; 26% of male Bangladeshis, compared to only 3% of females. This difference echoes the possible difference between the extent male and female Bangladeshis interact with the Rohingya regularly enough to become “friends”, as evidenced by responses to the previous survey question.

Geographic proximity appears unrelated to friendship; in both unions with refugee camps and without, the proportion is 15%. In unions such as Teknaf and Sabrang, where there are no Rohingya refugee settlements, there are large populations of Rohingya refugees from previous influxes within the host communities. This may explain why residents of these unions could have built stronger relationships with Rohingya through time.

“We have been living in a Rohingya-inhabited area, in Teknaf, for a long time. So, we are mixing with each other every day. Sometimes we also speak in Rohingya language to express our feelings.”

50-year-old Bangladeshi male, Teknaf

Interview participants stated that, even though interaction with the Rohingya is almost universal, friendship is too strong a word to describe the relationship:

“I interact with the Rohingya by working with them every day but even though I feel better every time I interact with them, I don’t have any Rohingya friends.”

Muhammad Nayeem, Liaison Officer, Nhilla

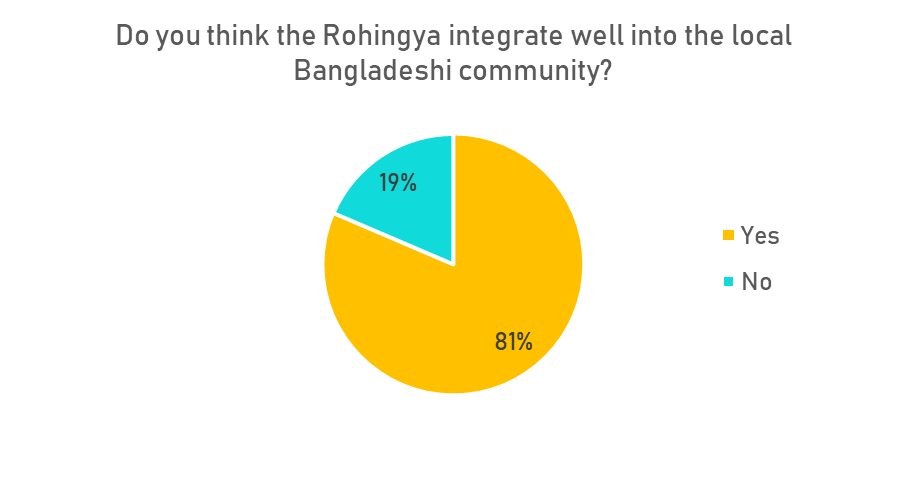

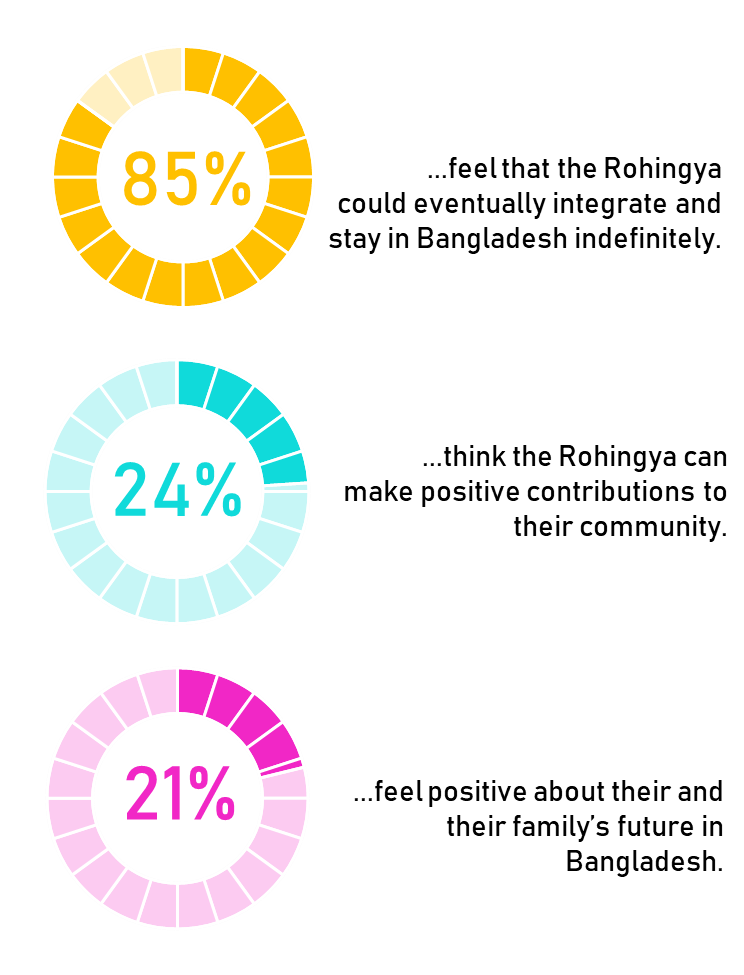

Rohingya Integration: Despite the fact that few Bangladeshis considered any Rohingya to be their friends, 81% of respondents believed that the Rohingya integrate well into the local community (91% of males to 71% of females).

This is in accordance with the frequency of interactions with the Rohingya; relatively more (86%) respondents in Rohingya-populated unions stated that the Rohingya do integrate compared to the remaining unions (76%). More Bangladeshis in Teknaf (90%) [90] believe this than in Ukhia (70%). [91]

Many respondents from Teknaf and Sabrang unions explained that the Rohingya have been living in their communities for many years, meaning that it is inevitable for them to mix with the locals. Therefore, despite the lack of any concrete integration policies, de facto integration is occurring.

“They already mixed with us a long time ago, because Teknaf is really a Rohingya-inhabited area. We have been living a long time at the bank of Myanmar.”

25-year-old Bangladeshi male, Teknaf

“They live very close to our local community area. For that reason, they can easily come to our local market, hospital, field, shop, mosque, etc. Thereby, they can easily follow our local culture.”

45-year-old Bangladeshi male, Nhilla

“They come and gossip at tea stalls in our localities.”

24-year-old Bangladeshi male, Ratna Palong

However, proximity and accessibility to the same places are not always enough for social integration. Sharing the same culture and religion with the Rohingya is the most important means of integration for the Rohingya, as explained by the majority of respondents. The Rohingya language is similar to the local Bengali and Chittagonian languages. Many locals reported that, because the communities understand one another linguistically, it facilitates communication and integration among them.

“Their culture is the same with our culture. Rohingya children and youth play openly and pass their time near our local community. So, they can easily follow our culture.”

35-year-old Bangladeshi male, Nhilla

Also, external appearance appears to play a positive role when it comes to integration for some respondents who said that Rohingya clothes and costumes are similar to the local Bangladeshis’.

Respondents also mentioned that the Rohingya have altered the local economy by engaging in cheap labour: local businessmen, shopkeepers, farmers, and hotel owners admitted to hiring Rohingya instead of Bangladeshis. Many homeowners also supported hiring Rohingya maids and cleaners for their houses. This indicates potential for conflict and competition between the two communities, as Bangladeshi workers may struggle to find work due to local wages being driven down.

However, integration via employment can also improve relations between the two communities by increasing interaction. For example, almost every fisherman interviewed said that they either worked with Rohingya, or see them fish nearby every day, which gradually improves the relationship between them.

“They come catch fish with us. And we don’t neglect them.”

50-year-old Bangladeshi male fisherman, Teknaf

“They are becoming so related. We like them.”

35-year-old Bangladeshi male fisherman, Teknaf

The Intermarriage Phenomenon: Respondents reported high rates of intermarriage, particularly between Rohingya women and Bangladeshi men, despite this being illegal, due to many marriages occurring without officiation. Whereas Bangladeshi male respondents were not overtly concerned by the high rates of marriage, Bangladeshi women expressed deep concern about intermarriages.

“Rohingya easily mix with our culture in many ways. Local people marry the beautiful Rohingya girls. Even our MP (Member of Parliament of Bangladesh) married a Rohingya girl! We live near the Bangladesh-Myanmar border. So, they can easily adopt our culture day by day.”

45-year-old Bangladeshi male, Sabrang

“The Myanmar border is very close to our local community. They can easily come and go this way. Some local young people have married the beautiful Rohingya girls. They even have had children. Every day we communicate with Rohingya in Teknaf. So, they can easily follow our local culture.”

35-year-old Bangladeshi male, Teknaf

“Bangladeshi boys are marrying Rohingya girls very easily; these girls have no demands.”

38-year-old Bangladeshi female, Sabrang

This phenomenon was explicitly addressed during the in-depth interviews, where interviewees explained in detail why Bangladeshi-Rohingya marriages are reportedly such a common phenomenon, despite laws against it:

“Rohingya girls are easy to marry Bangladesh boys. Even if the man’s wife is still there. Because the Rohingya girls are very beautiful, due to which the local people have it as their goal to marry them. The Rohingya girls agree to the marriage because if they marry local people then they will remain safe in Bangladesh.”

Rumana, Information Service Provider, Sabrang

“If they find any pretty Rohingya girl, they try to convince her Rohingya parents, who, in turn, find it secure to give their girl to the boys of the local community. On the other hand, the boys of the local community think that they never have to give them any ornaments or money to get married. That’s why it’s easier for the boys of local communities to get married [with Rohingya instead of Bangladeshi girls].”

Shameem, Service Provider, Baharchhara

“Besides, there are many Bangladeshi families that intentionally arrange marriages with Rohingya families only because they want to continue their drug businesses.”

Uddin, Field Assistant, Baharchhara

This indicates that Bangladeshi women perceive the increase in unmarried Rohingya women as a threat to Bangladeshi women and society at large, due to their perceived “beauty”, low bride price, and their insecure legal status leaving them vulnerable to exploitation. Interviewees indicated how this has caused marital issues within Bangladeshi families:

“I have a story to share. The son of the owner of our office got married to his cousin by affair. A few months later, a beautiful Rohingya girl started to live near there. After seeing the girl, the boy got excited to marry her. His first wife is still with him. What’s more, the boy’s father supported him strongly on this matter. As a result, the boy found it easier to bring his new wife. When his first wife tried to oppose her husband, he tortured her badly. On the other hand, her parents are totally careless to their daughter. Because, it was only her decision to get married to the boy.”

Shameem, Service Provider, Baharchhara

“Most Bangladeshi women are housewives; they depend on their husbands. As a result, they can’t do anything if their husband gets involved with a Rohingya girl or even get married with them. They have to remain silent or endure it. Hence, out of neglect, they call Rohingya girls prostitutes. They think that unhappiness and instability in families is only because of Rohingya girls.”

Ashik, Team Leader, Nhilla

“Bangladeshi women are facing conjugal problems. Here, polygamy is rising as well as philandering. Most local Bangladeshis are passing their nights at Rohingya camps. So, to say, domestic instability is rising day by day. Rohingya-Bangladeshi marriages are still in control now. But is seems that it will be uncontrollable soon if proper steps won’t be taken.”

Uddin, Field Assistant, Baharchhara

Many respondents also added that the Rohingya integrate using illegal methods, by creating illegal IDs and birth certificates with the help of local forgers, which in turn makes it easy for them to mingle and send their children to local schools, as well as giving them the ability to move freely across the country undetected.

“They are making Bangladeshi national ID cards through bribes. As a result, they are spreading across the country. Also, many Bangladeshi boys are marrying Rohingya girls because these girls have no demands.”

31-year-old Bangladeshi female, Teknaf

“They don’t want to go back to their own country. They manage birth certificates by different tactics and admit their children to Bangladeshi schools. Thus, their children are taking education with the local community.”

Shameem, Service Provider, Baharchhara

However, several respondents did not agree that Rohingya integration was occurring at all because they are restricted to their camps, and therefore not given the opportunity to mix with the local people.

“They are living in a bounded area and the administration of Bangladesh appointed police, rapid action battalion, and army to look after them.”

30-year-old Bangladeshi male, Haldia Palong

“There is no Rohingya available here, so they don’t mix with us.”

26-year-old Bangladeshi male, Teknaf

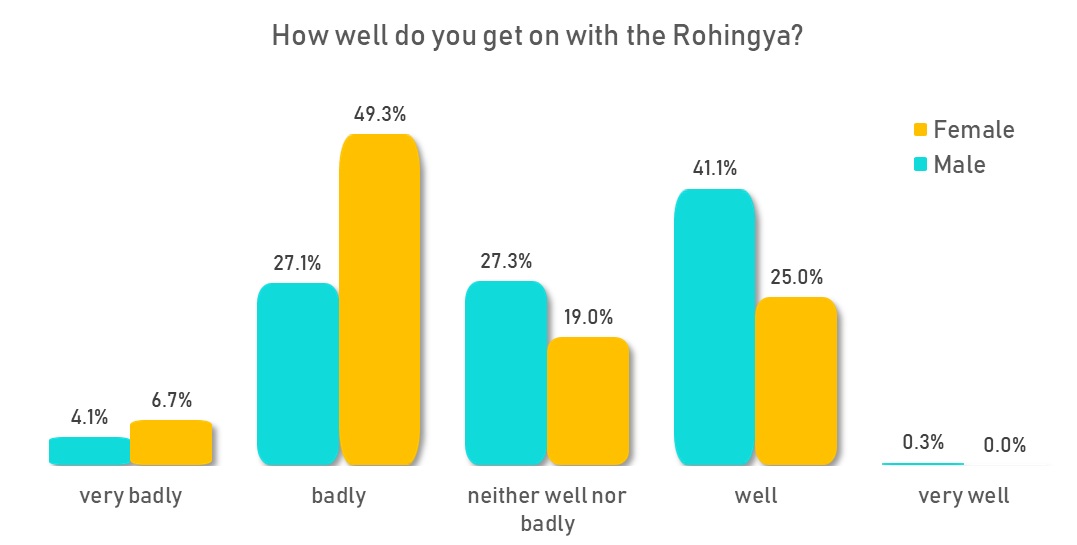

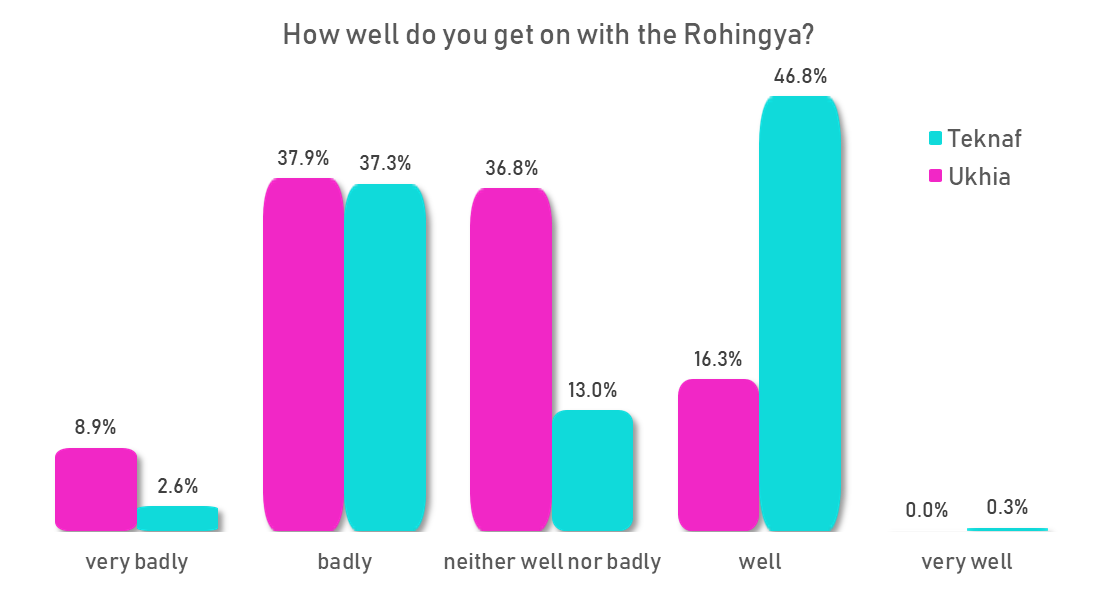

Quality of relationships with the Rohingya: When the respondents were asked to evaluate the quality of relationships with the Rohingya on a five-point Likert scale, 34% reported getting along well or very well, 43% getting along badly or very badly, and 23% were neutral (neither well nor badly). The extremes were: 0.2% very well and 5% very badly.

There were significant regional variations on both a union level and between upazilas. Relatively more residents of unions with a high Rohingya presence stated they got along well (40%) and fewer badly (34%) than unions without a strong Rohingya presence (26% and 42%, respectively). Between upazilas, more respondents from Teknaf responded that they get on well than from Ukhia (47% and 16%, respectively).

The level of education of the respondents could be related to the relationship with the Rohingya: more respondents with university educations stated that they get along with the Rohingya than those with lower levels of formal education, or without. Of those who were either bachelors or masters graduates, 63% reported getting along well with the Rohingya compared to only 34% of those with either primary or secondary education, and 11% of those without formal education at all. Of those 91 people who reportedly did not get along with the Rohingya at all (very badly), 69% have either just primary, informal, or no education at all.

This could indicate that those with higher educations are more receptive and open to the Rohingya; this could be due to their different perceptions of the other, or due to the limited competition between those with higher educations and the Rohingya, compared to less educated Bangladeshis.

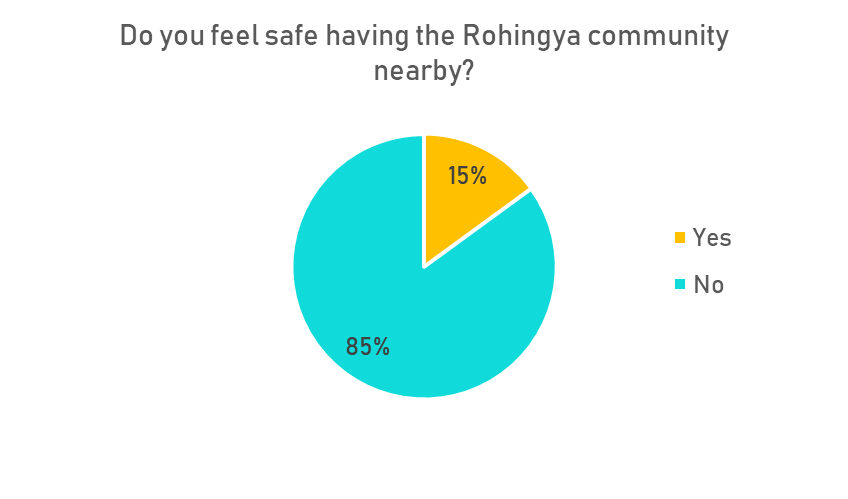

Safety: A staggering 85% of residents of the two southernmost upazilas of Bangladesh stated that they did not feel safe having Rohingya refugees living nearby. This was true for both sexes and residents of both upazilas, who universally agreed at about 85%.

However, it should be noted that in Nhilla and Whykong, unions with significant Rohingya populations, only a few residents reported feeling safe – fewer than 2% and 6%, respectively. This compares to relatively higher proportions in other unions, ranging from 14% to 37%.

“After the recent arrivals of Rohingya, crime has increased. Cultural and moral deterioration have increased. We want a permanent solution to this problem. International communities should provide sufficient food, shelter, and health services [for them] until they [Rohingya] go back to their own country.”

27-year-old Bangladeshi female, Whykong

“Initially, Bangladeshi locals received the Rohingya cordially. Basically, the local people gave them shelter in their courtyard to minimise their sufferings. But at first, there lived one family. Now there are five families there. Their population is increasing. And that is causing security concerns.”

Uddin, Field Assistant, Baharchhara

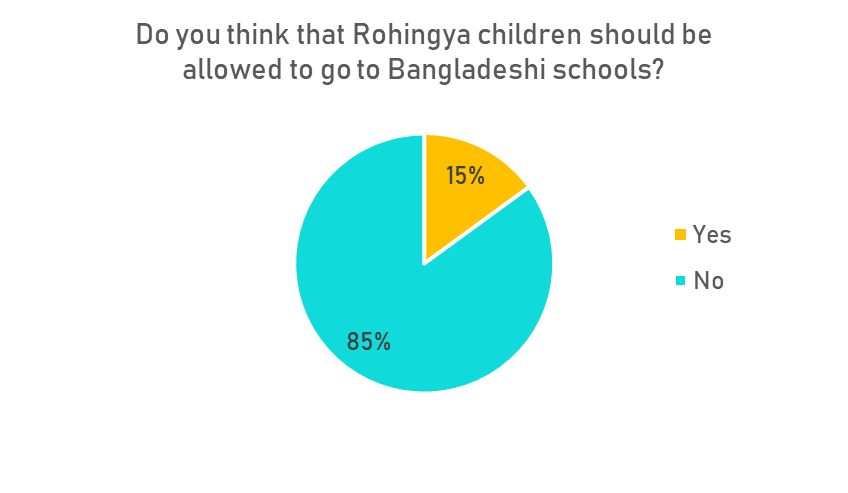

Rohingya children’s education: Bangladeshi respondents were reluctant to allow Rohingya children to go to the same schools as their own children. More specifically, 85% believed that Rohingya children should not go to Bangladeshi schools; almost all (98%) female respondents, compared to three in four (74%) males.

Interestingly, the majority (58%) of those respondents who earlier stated that they have Rohingya friends said they did not want the Rohingya children in their local schools. Moreover, only one in ten (10%) respondents who did not have Rohingya friends supported Rohingya children being allowed an education in local schools. Once again, residents of Nhilla and Whykong, irrespective of their sex, were universally negative (99%).

“The Rohingya didn’t come here to live permanently. They came here for a temporary time. In my view, they should not be given permission to [go to] Bangladeshi schools. Is it worth it learning the Bengali language? It will be totally useless for them. And also, if they manage to do so, it will be very hard to send them back.”

Uddin, Field Assistant, Baharchhara

The majority of respondents found that one’s nationality should be the main determinant of who is accepted to or rejected from schools.

“They [Rohingya] are not our country’s citizens. So, they have no right.”

35-year-old Bangladeshi female, Ratna Palong

“They [Rohingya] are not citizens of Bangladesh by birth. As Bangladesh government tries to send them back to their own country, it’s not a wise decision for the Rohingya children [to go to our schools]. Their long-born culture would be changed by this. I think they should grow up within their own culture.”

19-year-old Bangladeshi female, Nhilla

This view is reflective of government policies which perceive the Rohingya as temporary guests who require imminent repatriation. Thus, respondents were protective of their children’s education system; the Rohingya are regarded as non-citizens who do not qualify for access to education for their children, despite the vast number of Rohingya children growing up in the camps without access to formal education. This could be due to the lack of facilities available or a fear that the quality of education may deteriorate as a result.

“They [Rohingya] don’t have Bangladeshi identity. In our local community there is a shortage of educational institutions. So, giving access [to Rohingya] children will have a negative impact on our local educational institutions.”

35-year-old Bangladeshi male, Nhilla

In addition to this, many claimed that Rohingya children are not brought up with the same values and ethics as their own children.

“Rohingya children are not so good; they quarrel with our children.”

35-year-old Bangladeshi male, Baharchhara

“Children of Rohingyas are very dirty. They behave uncultured.”

24-year-old Bangladeshi male, Teknaf

Others believed that the Rohingya have more opportunities within the camps, where NGOs provide them with basic education and that if they are educated in Bangladesh they will be less likely to leave.

“They study in their camp safely, so why would they need to study in our school?”

54-year-old Bangladeshi male, Teknaf

“We don’t even have enough teachers and educational facilities for our children. If the Rohingya children are allowed to go to Bangladeshi schools the quality of education will be deteriorated. Also, their literacy can’t bring any good result for us.”

40-year-old Bangladeshi female, Teknaf

“If they study at our schools, they will mix with us. After that we will not be able to find out who is a Rohingya and who is not.”

32-year-old Bangladeshi male, Raja Palong

“As they aren’t permanently in Bangladesh, they will eventually migrate. And then, they can’t be separated if they know the language of Bangladesh.”

40-year-old Bangladeshi female, Nhilla

“They aren’t citizens of Bangladesh by birth. Nor Bengali speakers. As Bangladesh government tries to send them back to their own country, it’s not a wise decision for the Rohingya children [to go to our schools]. Also their long-born culture would be changed by this. I think they should grow up within their own culture.”

35-year-old Bangladeshi female, Whykong

However, some respondents (15%) explained why Rohingya children should not be deprived of their right to education. A few supported the Rohingya desire for permanent residence in Bangladesh, and therefore their education as a means of achieving integration. Others supported that, due to the lack of educational facilities in the Rohingya communities, the Rohingya children had limited options for education and would turn to Bangladeshi schools for education. In addition to these responses, religion was also mentioned; being Muslim is a good reason for the locals to accept Rohingya in their schools.

“Education is the backbone of a nation, so they should study in our schools.”

32-year-old Bangladeshi male, Teknaf

“Since they are Muslim, they have the same rights to go to our schools.”

31-year-old Bangladeshi male, Baharchhara

Some expressed empathy for the Rohingya’s situation and believed access to education for their children was a fundamental right.

“They also are human beings. They have the right to education. So, I think the Rohingya children should be allowed to go to Bangladeshi schools.”

22-year-old Bangladeshi female, Teknaf

“Illiteracy is the root cause of Rohingya people’s sufferings. So, we should encourage them take up education and also make them interested in birth control.”

37-year-old Bangladeshi female, Sabrang

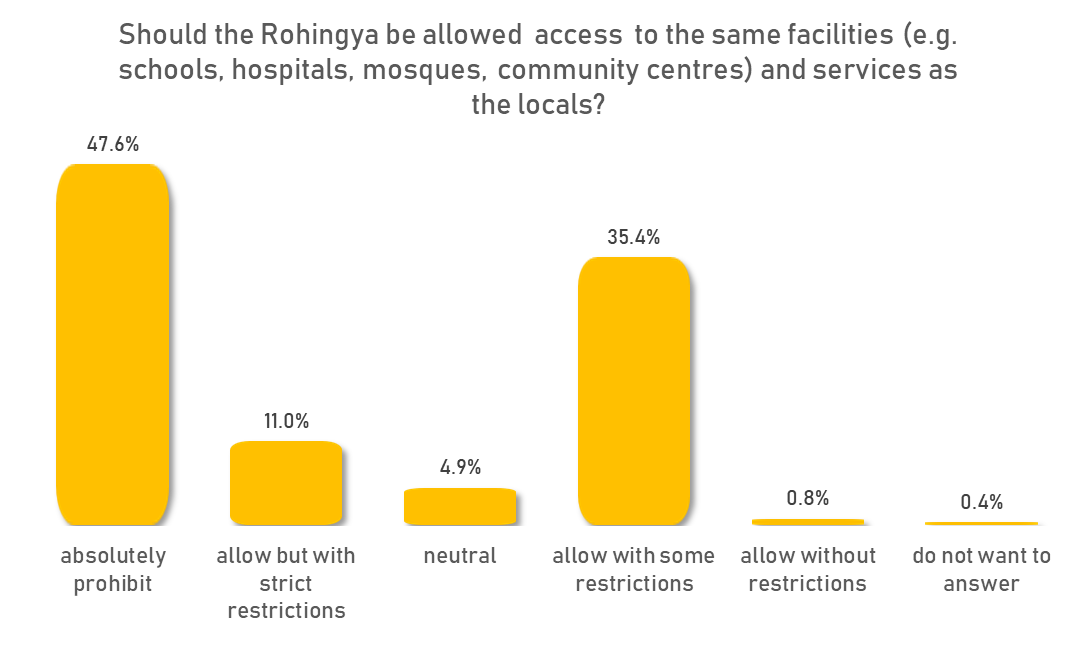

Access to facilities: Almost half (48%) of all respondents supported absolute prohibition of the Rohingya from using the same facilities (e.g. hospitals, schools, mosques, community centres) and services as the locals, while only a minority (0.82%) believed the Rohingya should be allowed to use the same facilities and services as them without any restrictions. Only a few people (5%) took a neutral stance, and 0.35% avoided commenting at all on the matter.

Overall, 59% stated that the Rohingya should be absolutely prohibited or allowed but with strict restrictions. However, 36% stated that the Rohingya should be allowed with some restrictions or allowed without restrictions.

However, it should be noted that the answers varied significantly between the two sexes: of those who were in favour of prohibition, 89% were women; of those who supported that Rohingya could be allowed but only with strict restrictions, 93% were men and; of those who supported some restrictions, 91% were men. 89% of those who never see Rohingya supported absolute prohibition.

“If they want to stay in our country, they have to follow specific rules.”

23-year-old Bangladeshi male, Sabrang

As explained by the participants of the in-depth interviews, the locals are resistant to the Rohingya having access to all facilities due to their own needs:

“We allow them in hospitals and mosques, but we can’t give them support in education and employment. Because in our country, there is need of employment. If we allow them in education and employment, then unemployment will increase.”

Shameem, Service Provider, Baharchhara

Competition between the two communities was also evident, particularly for humanitarian relief:

“There are many poor people in our country. Rohingya people get food, they get protection, nutrition, and medical support from NGOs. Local poor people are deprived of these facilities.”

Rumana, Information Service Provider, Sabrang

“They may get medical aid and go to our mosques to pray at least. But they can’t be given access to other facilities. If they get a chance to go to our schools, then they will try to live here permanently.”

Ashik, Team Leader, Nhilla

Perceived changes since the recent Rohingya arrivals

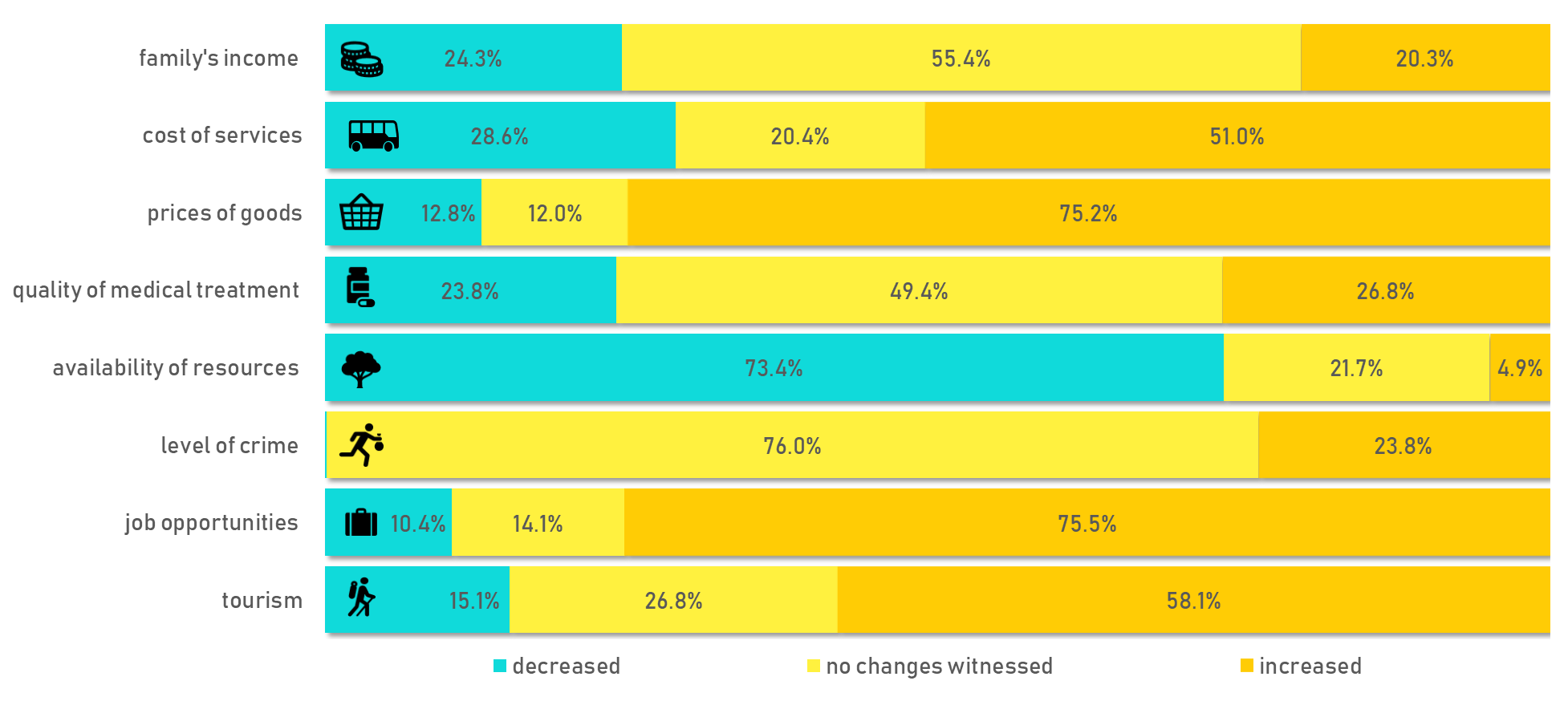

Income: The majority (55%) of respondents stated that their income has neither increased nor decreased since the arrival of the Rohingya: 88% of males supported that it either stayed the same (62%) or increased (26%), compared to 62% of the females (48% and 14%, respectively). One in five respondents (20%) said that their income had increased. [92]

This supports the perceived increase in job opportunities, in which 76% (92% of females and 60% of males) of local Bangladeshis indicated that job opportunities have increased since the latest Rohingya arrivals. This could suggest that the increasing refugee presence has led to the creation of new jobs, as supported by all in-depth interviewees:

“Earlier, in Baharchhara there was not much chance of employment. But now, after recent arrivals of Rohingya there have been more job opportunities created for the Bangladeshi locals. Because many NGOs have come here to work for the Rohingya, either by supplying food to them, making shelters, or giving aid to them. NGOs are recruiting local people for their work. Overall, job opportunities have increased.”

Uddin, Field Assistant, Baharchhara

However, others also stated that the reported increase in employment competition has had an effect on the livelihood of locals who already struggled financially prior to the Rohingya influx:

“The price of daily goods has increased but the income of poor people remains the same or even decreased. Because Rohingya are taking half wages by doing the jobs where local people would get full wages. As a result, local poor people are facing a serious unemployment problem. Their poverty is rising.”

Rumana, Information Service Provider, Sabrang

However, despite more opportunities in the job market, interviewees feared a negative consequence of this was that Bangladeshi youth were giving up on their education to work in NGOs and refugee camps.

“Now, the local boys and girls are leaving their studies and working in the Rohingya camp. As a result, the ratio of people in higher education is decreasing.”

Shameem, Service Provider, Baharchhara

Public Services: Half (51%) of adult Bangladeshis living in Teknaf and Ukhia perceived that public services, such as transportation, have become more expensive over time since the recent Rohingya arrivals. Many more residents of Teknaf reported this (74%) than Ukhia (22%), with half (50%) of residents of Ukhia stating that their cost has decreased.

Prices of Goods: The prices of goods, such as vegetables, fish, and meat, have reportedly risen according to the majority of respondents (75%); there was a wide discrepancy observed between female (96%) and male respondents (56%) possibly due to differing gender roles within the Bangladeshi household.

Availability of Resources: The availability of resources such as water and firewood, has reportedly decreased (73% of respondents; 82% of Teknaf residents, 62% of Ukhia residents) due to cultivatable land being used for camps, and bad camp management making local communities’ farmland unusable. Thus, Teknaf seems to be perceived as experiencing this more than Ukhia. [93]

“Some Rohingya camps were built in local cultivatable land. Hence, people cannot cultivate the land anymore and if they [Rohingya] migrate soon, it will be better for us.”

65-year-old Bangladeshi male, Haldia Palong

“Because of them [Rohingya] prices of goods and the cost of living are rising. Our living environment is becoming unhygienic day by day. So, Rohingya repatriation is very important for us.”

30-year-old Bangladeshi female, Teknaf

“All things, like cultivatable land and dwelling houses, everything has started to be affected badly. The lands of the local people are becoming occupied by the Rohingya. Because of which, the land area is decreasing day by day. Production of crops is hampered. Food supply is not growing according to the needs of the people. As a result, prices of goods have increased.”

Rumana, Information Service Provider, Sabrang

Medical Treatment: The majority (49%) of respondents had not witnessed any significant changes to the quality of medical treatment. However, there was a significant regional difference, as four in ten (41%) of Ukhia residents compared to only one in ten (10%) of Teknaf residents supported that the quality has worsened over time.

35% of those living in Rohingya-populated unions believed that the quality of medical treatment has increased compared to only 16% of their counterparts, which could be an outcome of the increase in medical support for Rohingya provided in these unions, where local Bangladeshis are also welcome.

Tourism: Respondents reported that tourism has increased (58% of respondents). This may be due to the increase in international personnel now working in humanitarian organisations in the district. This was more so in Teknaf (80% of respondents, residents of Teknaf) than in Ukhia (30% of respondents, residents of Ukhia), which could be because Teknaf is known for its landscape, beaches, and lodges.

“Tourism has increased. Because foreign men are coming here to observe the Rohingya situation.”

Uddin, Field Assistant, Baharchhara

Crime Rate: Almost all respondents (99.8%) believed that the rate of crime had either increased (24%) or had not changed (76%) since the Rohingya arrived. Female respondents stated more frequently that it had increased (36%) compared to males (13%).

Interestingly, 16% of people living in unions with Rohingya settlements perceived that crime had increased compared to a lesser 8% in other unions. Those who perceived that the crime rate increased related it to the rapid population growth and density:

“If a huge population lives in a constrained area for a long time, then crimes might happen there [by those] in need of food and shelter. Recently, some problems are seen in this area. Drug addiction has become a serious problem for Bangladesh. Those drugs come from Myanmar and trafficked through Teknaf and Ukhia areas. The main reason behind the increasing number crimes is that when the Rohingya came to Bangladesh from Myanmar, they had some money or assets with them. But a few days later, that was finished. The relief which is given to them is basically food. But they want to lead a better life by earning money. For this reason they become involved in various types of crime.“

Rumana, Information Service Provider, Sabrang

The major causes for this were perceived to be due to the inability of the Rohingya to find legal employment to cover their needs, pushing them into criminal acts such as robberies, drug trafficking, and prostitution:

“The aid which the International Community sends for Rohingyas is not sufficient for them. For this reason, they are involved in crimes like prostitution, and drugs and human trafficking.”

35-year-old Bangladeshi female, Baharchhara

However, it was noted that the Rohingya are vulnerable to exploitation by locals due to their lack of education:

“Rohingya people have no moral and institutional education. Therefore, some notorious Bangladeshi people encourage them to become involved in crime. And actually, different types of crime, like prostitution, drug trafficking, and robbery for economic insolvency.”

20-year-old Bangladeshi female, Whykong

“Local criminals use them to commit crimes. It’s a great problem for us.”

55-year-old Bangladeshi male, Nhilla

“Day by day, the Rohingya are involved in crime in many ways; they have brought Yaba, the most destructive drug, from Myanmar to Teknaf with the support of locals.”

45-year-old Bangladeshi male, Sabrang

Other respondents felt the responsibility lay with the Rohingya themselves for the increase in crime:

“Their mind is so narrow; they do many bad works.”

30-year-old Bangladeshi male, Baharchhara

“Our villagers learn from Rohingyas how to commit crimes.”

50-year-old Bangladeshi male, Baharchhara

“Rohingya girls and women should be aware of their rights to live a healthy life, where they won’t be persuaded by any miscreant who wants to take advantage of them.”

40-year-old Bangladeshi female, Nhilla

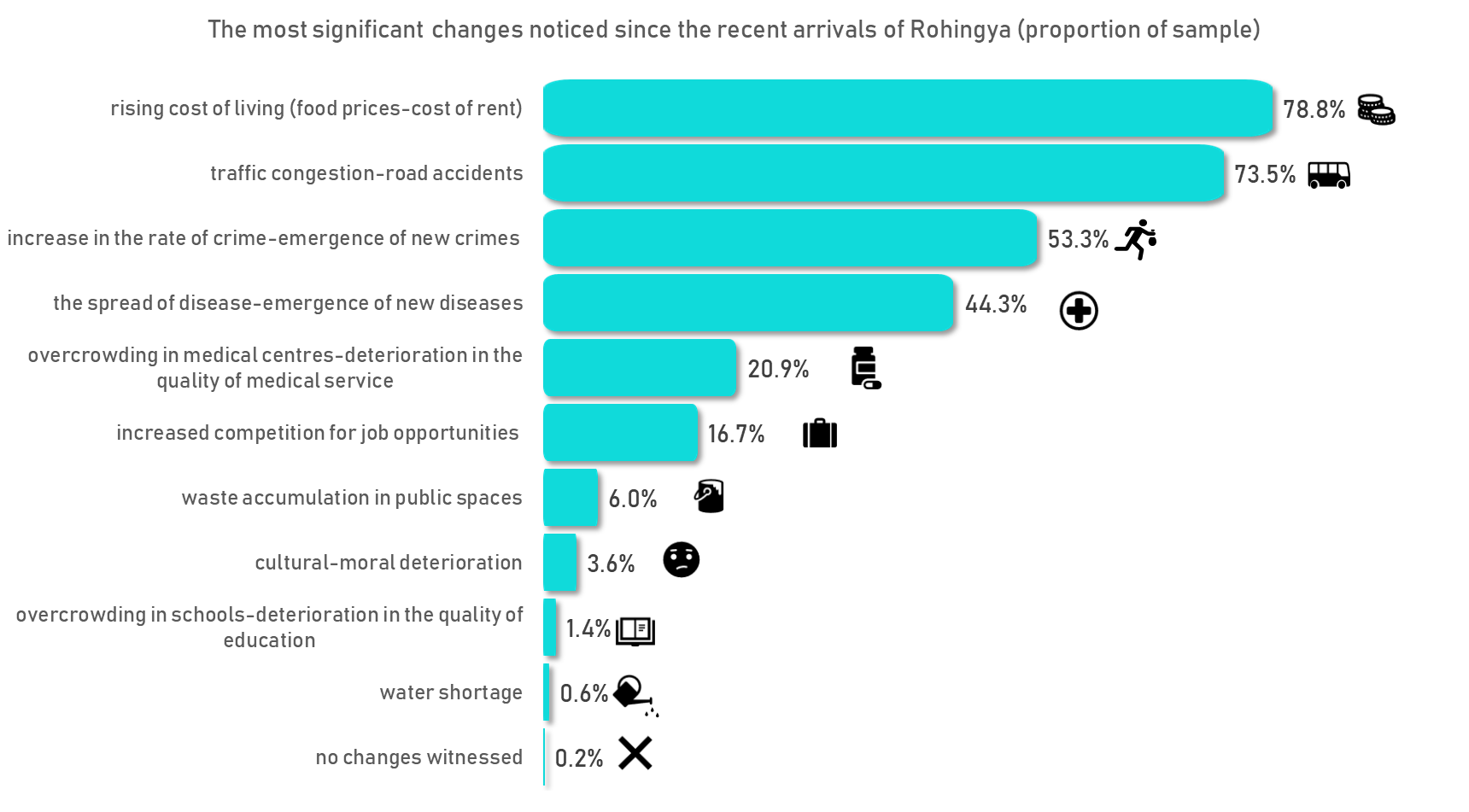

Most significant changes noticed: Respondents indicated that the rising cost of living (79% of respondents), traffic congestion and number of road accidents (74% of respondents), and a perceived increase in the rate of crime and the emergence of new crimes (53% of respondents) were the most significant changes witnessed since the recent arrivals of the Rohingya.

“We can’t move freely due to the traffic jams. It will be good for our local communities if this crisis be solved as early as possible.”

35-year-old Bangladeshi male, Haldia Palong

With regards to job opportunities, there was a significant difference between the two sexes: one in four (27%) male respondents stated that they had noticed an increase in competition for job opportunities, compared to 5% of female respondents. Some stressed having significantly more job opportunities before the Rohingya arrivals.

“They come here and work at a little price. Then we suffer. We do not get the job.”

18-year-old Bangladeshi male, Baharchhara

It is important to notice that just three out of 1,697 respondents mentioned that they have witnessed no changes

Beliefs about Rohingya repatriation and future

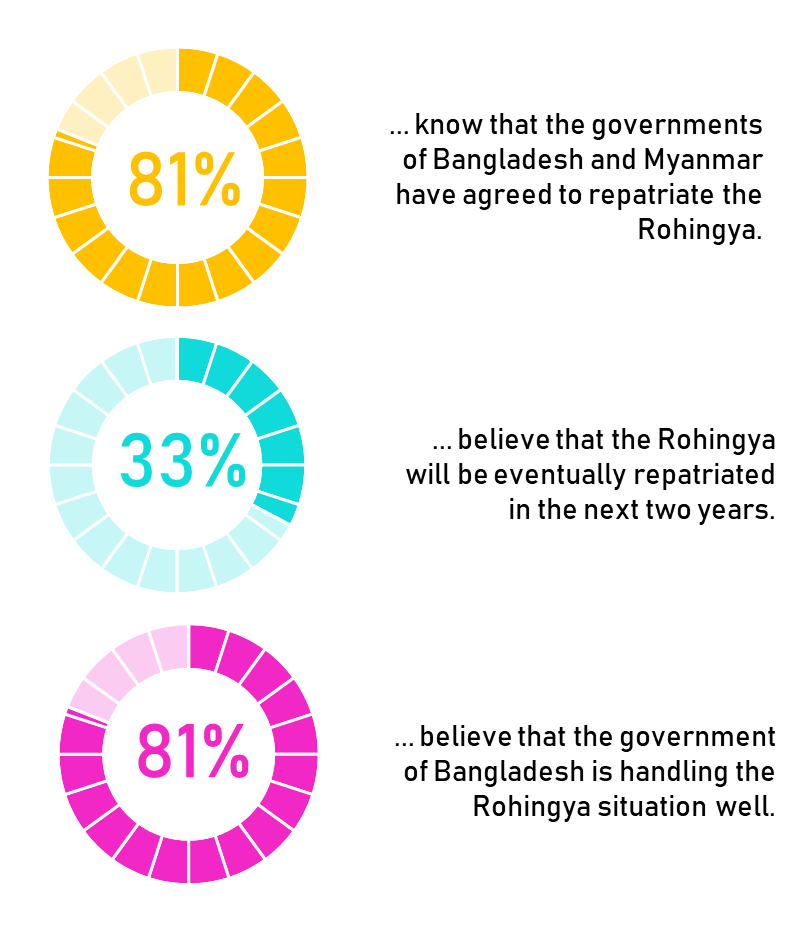

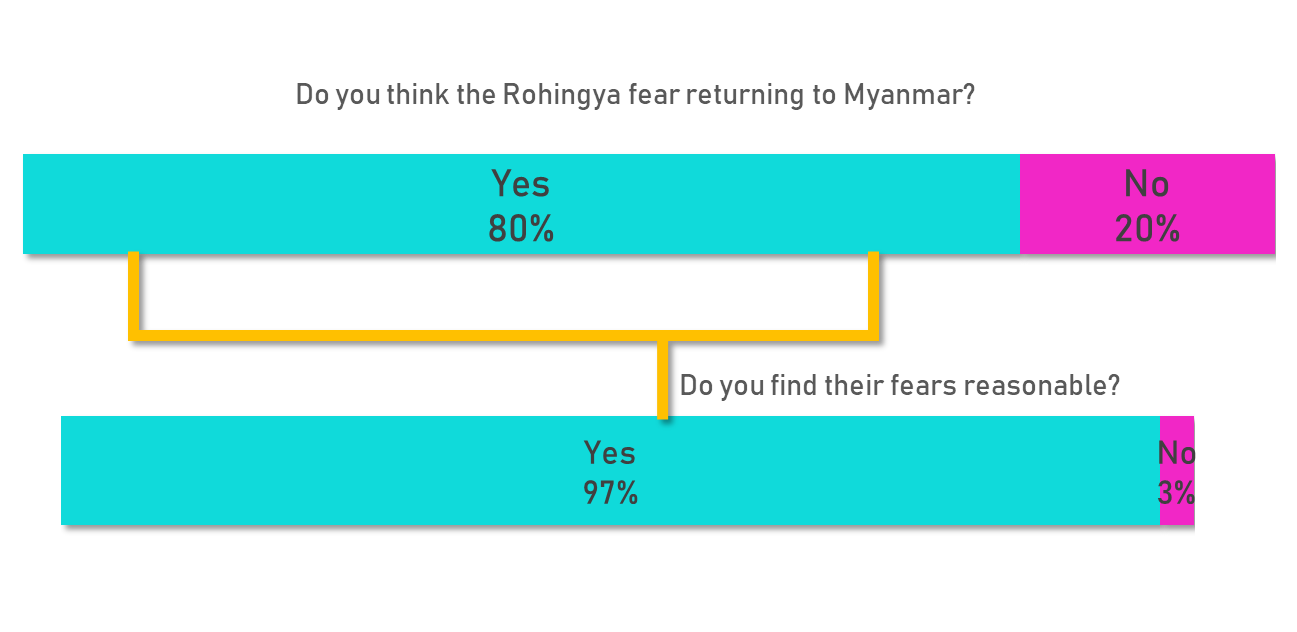

Knowledge of Rohingya repatriation: A large proportion of respondents were aware of the repatriation deal between the governments of Myanmar and Bangladesh (81% of residents of either Ukhia or Teknaf upazila). [94] However, one in five (19%) had not heard about it at the time of the survey.

This is worthy of comparison to Xchange‘s Repatriation Survey, in which only slightly more than half (52%) of the Rohingya were found to have knowledge about the repatriation deal between the governments of Myanmar and Bangladesh.

This is likely due to Bangladeshis having better access to information through various means.

“They need to wait patiently for the decision made by UN, Bangladesh, and Myanmar governments to regain their rights back at their home.”

35-year-old Bangladeshi female, Whykong

Timing of repatriation: Only 33% of Bangladeshi locals expected repatriation to occur within a period of two years; the majority (67%) believed that the Rohingya would not be repatriated within the next two years or at all. This could be due to the Bangladeshis’ awareness of the previous repatriation deals, which took many years to execute.

In Xchange’s Repatriation Survey, the Rohingya were found to be more optimistic that repatriation will eventually happen in the next two years (78% of respondents).

Disaggregated by sex, slightly more male respondents were positive that repatriation would occur in the near future (51%), while the majority of female respondents (88% of all women) did not expect repatriation to occur in the next two years.

In-depth interview participants showed awareness of the importance of the relationships between the Bangladeshi and Myanmar governments and the international community and the role that each played in the agreement:

“It’s been shown that unless Myanmar and the international community made several discussions, no fruitful solution can be found. Yes, it [repatriation] will happen, but I don’t know if it is possible to happen within the next ten years.”

Shameem, Service Provider, Baharchhara

“In my opinion, the proposed repatriation process is an excellent initiative. Actually, Myanmar doesn’t seem to be as cordial as the Bangladeshi government on this matter; they are totally indifferent about this issue. The UN and other super powers should put pressure on the Myanmar government to agree with this proposed repatriation process. When it will happen is uncertain to me. It totally depends on the well-meaning attitude of the world community and Myanmar government.”

Ashik, Team Leader, Nhilla

“My opinion about the proposed repatriation is that it is a great initiative but to successfully implement this repatriation process, Rohingyas have some demands which have to be fulfilled, certainly. Otherwise, they are not willing to back their own country. Basically, the proposal for their repatriation must be adjusted to their demands. In other words, if not, they are not eager to go back. Because they think that they are in a better condition in Bangladesh than in Myanmar.”